Tanaan on sata vuotta Verdunista.

Battle so bloody men called it the MEAT-GRINDER: One of history's most savage sieges began with a hail of shots a century ago and left 250,000 dead...yet achieved NOTHING

- On February 21, 1916, a Monday, the first shots were fired in the battle for the French fortress town of Verdun

- The Battle of Verdun would last for ten months, making it the longest battle of the war, twice as long as any other

- Often a hell overlooked, Verdun was an entirely Franco-German affair which ended in 'bitter disillusionment'

By

TONY RENNELL FOR THE DAILY MAIL

The truth hit home for the German soldier with all the impact of one of the millions of artillery shells buzzing through the air at the Battle of Verdun during World War I.

He was digging a trench when his pickaxe became entangled in a bundle of slime. On the end were human entrails — all that was left of a dead man buried there by a previous bombardment.

‘Until then, I had seen the dead without really seeing them, like figures in a waxworks. But now the words closed upon my brain like a vice. A dead man. They choked my throat and chilled my heart.

‘All these corpses had been men who breathed as I breathed, had had a father, a mother, a woman whom they loved, a piece of land which was theirs, faces which expressed joy and suffering, which had known the light of day and the colour of the sky.

‘It was a moment of realisation. After that, I could never pass a dead man without stopping to gaze on his face, stripped by death of that earthly patina which masks the living soul.

‘And I would ask, who were you? Where was your home? Who is mourning for you?’ Ernst Toller’s words should give us all pause for thought as we mark — not celebrate, never celebrate — another grim milestone in that blood-drenched, pointless war.

+14

One hundred years ago, on February 21, 1916 - a Monday - the first shots were fired in the battle for the French fortress town of Verdun. Pictured here, a French soldier falls after being shot in no-man's-land at Verdun

+14

The battle that raged for ten terrible months: Soldiers wait in the trenches as they prepare to make their way 'over the top' to face the enemy

+14

German and French soldiers fought for every last metre of ground, making it the longest battle of the war. Here, French soldiers are moving into attack from their trench during the Verdun battle

One hundred years ago, on February 21, 1916, a Monday, the first shots were fired in the battle for the French fortress town of Verdun. It would last for ten terrible months.

German and French soldiers fought for every last metre of ground, making it the longest battle of the war, almost twice as long as any other encounter.

In the 303 days of this so-called ‘meat-grinder’, close to 750,000 men died, were wounded or simply disappeared, pulverised to tiny, unrecognisable bits by shelling from as far as 17 miles away, or eviscerated on the end of a bayonet in man-to-man, whites-of-their-eyes grappling.

The numbers of casualties are so huge that our eyes glaze over. All those noughts can blind us to the reality of what they mean. Toller’s words remind us what is too easily forgotten as we look back: that each and every one was a living, breathing person, cut down and cut short in his prime.

And to what purpose?

As he also noted: ‘We were cogs in a great machine which sometimes rolled forward, nobody knew where, sometimes backwards, nobody knew why.’

From the other side of the no-man’s-land that separated the two armies, a French counterpart, Albert Joubaire, summed up his experience at Verdun: ‘What a bloodbath, what horrid images, what a slaughter! Hell cannot be this dreadful.’

It was a hell often overlooked. British histories tend to pass over Verdun in a few pages. That’s because it was an entirely Franco-German affair, re-running an old and bitter rivalry between those two nations, particularly over the border area in the east of France where the fortified city was sited.

It had been a fought-over, front-line fortress for centuries, with huge strategic implications.

When war broke out in 1914, it was just 25 miles from France’s frontier with Germany. It also straddled the shortest direct route from Germany to Paris. Take Verdun, and the Kaiser’s army could be in the French capital in days.

+14

In the 303 days of the so-called ‘meat-grinder’, hundreds of thousands of men died, were wounded or simply disappeared. This image shows a French soldier's grave, marked by his rifle and helmet, on the battlefield

+14

French soldiers moving into attack from their trench during the Verdun battle. When war broke out in 1914, it was just 25 miles from France’s frontier with Germany. It also straddled the shortest direct route from Germany to Paris.

The city itself stands on the River Meuse, its citadel and cathedral looking out over the countryside, where the French had over the years built dozens of forts and concrete casements for artillery.

They fanned out in a semi-circle six miles deep and with a perimeter of 30 miles, forming at that time the most modern and heavily defended military complex in the world.

Inside this concrete fortification were more than 400 field guns, billeting for 5,000 troops, its own airstrip and a narrow-gauge railway linking its principal parts for the speedy dispatch of men and ammunition to where they were most needed.

Bristling and defiant, the tricolours waving in the breeze seemed to say to the Germans: don’t you dare.

But dare was precisely what the Kaiser’s generals decided on in 1916. And not just out of bravado. There was a reasoned, if horrific, military objective involved.

What horror! Hell cannot be this dreadful

The war was at a stalemate. The German armies advancing through Belgium in 1914 and 1915 had been battled to a standstill across northern France by British and French troops. German General Erich von Falkenhayn’s assessment was that the British were the main threat to German success.

But before the British could be addressed directly, France, already war-weary, depleted and demoralised, needed to be taken out of the equation.

And the place to do that, he advised the Kaiser, was at its military pride and joy — Verdun. He proposed a deliberate battle of attrition there.

Not willing to surrender the city, the French High Command would pour in reinforcements, sucking in more and more lambs to the slaughter.

Reckoning on a kill-ratio of five French poilus (bearded soldiers) for every two Germans, Von Falkenhayn promised to ‘drain France’s life-blood’ and win the war. Never were the brutal mathematics of the Great War so clearly and callously laid out.

A similar numbers game was applied to the weapons he deployed.

More than 1,200 big guns — some with barrels 50ft long — were dragged to the front by horses, set up along a wooded escarpment and aimed at every inch of the French lines.

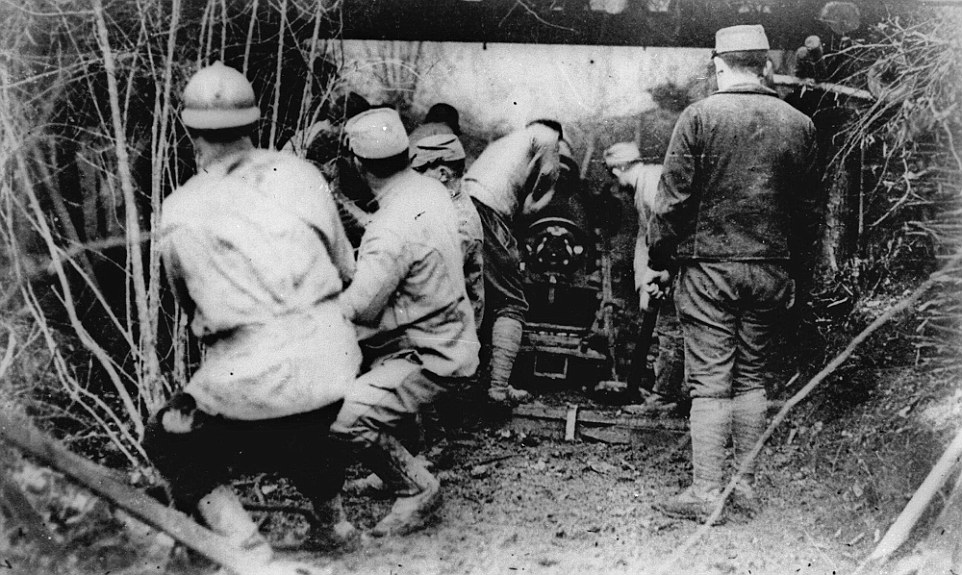

French troops moving a howitzer during the Battle of Verdun. In just one 15,000-strong division, 9,000 men were dead, wounded or missing. Another lost a third of its strength in just 36 hours

The trenches: As German soldier Ernst Toller dug a trench, his pickaxe became entangled in a bundle of slime. On the end were human entrails — all that was left of a dead man buried there by a previous bombardment

Some 1,300 trains shipped in 2.5 million shells (some filled with poisonous gas), enough for a non-stop six-day barrage. A further two million shells were stockpiled, awaiting transportation.

It was the largest concentration of artillery in history. Instructions to the crews were that ‘no enemy line is to remain un-bombarded, no routes of supply unmolested, nowhere should the enemy feel safe’.

At 4am on February 21, under a full moon, the first shots were fired by three massive guns, hitting Verdun itself and destroying the railway station.

The rest then joined in, targeting the seven-mile French front line of trenches and fortifications with what one of those on the receiving end described as ‘a gale of flame’.

Shells came crashing out of the fog of smoke and dust, a French officer recorded, ‘and we have to abandon our shelter and go to ground in a deep crater. We are surrounded by wounded and dying men whom we are totally unable to help’.

Blinded and injured soldiers kept falling on us

After nine hours, the barrage ceased and German assault troops rose from their trenches and moved forward across the shattered ground, some armed with a new weapon of horror, the flame-thrower, making its battlefield debut. French trenches burned, with men inside them.

In that first onslaught, the French line was pushed back a mile. Over the next three days, they would be forced to retreat a further three miles. Losses were dreadful.

From one 15,000-strong division, 9,000 men were dead, wounded or missing. Another lost a third of its strength in just 36 hours. Badly injured bodies lay everywhere, with field ambulances unable to cope and the roads back to the hospitals made impassable by shelling.

After five days, it looked all over for the French.

Fort Douaumont, one of their key strongholds, fell to the Germans and morale plummeted. Civilians began pouring out of Verdun itself, fearing the city was about to fall.

Troops in the trenches around the fortress of Verdun preparing for attack. The German soldier Ernst Toller wrote: 'All these corpses had been men who breathed as I breathed, had had a father, a mother, a woman whom they loved, a piece of land which was theirs'

A French soldier in the Battle of Verdun pictured in an advanced trench protected by barbed wire, watching the enemy positions through a periscope

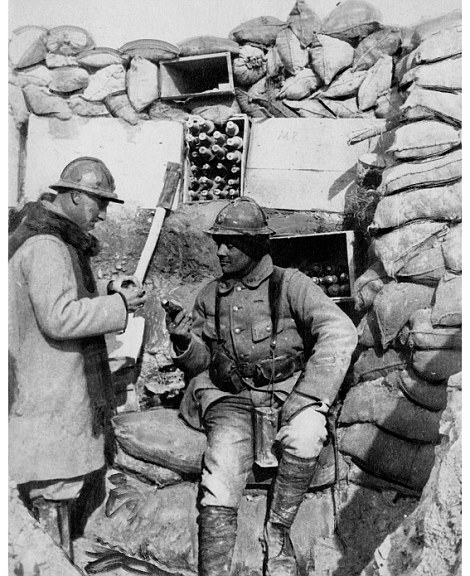

Left, French soldiers are pictured sheltering in the underground bunkers at Verdun, and right, French soldiers preparing hand grenades in a trench

And, indeed, it might have made sense for the French to concede Verdun at this point, to pull back their depleted but still relatively intact army and regroup in the Forest of Argonne closer to Paris.

But, as Von Falkenhayn had predicted, French pride got the better of military sense.

From Paris, the order came to hold Verdun at all costs. A new commander was sent, General Philippe Petain, with the watchword accredited to him but, in fact, cribbed from another general, ‘Ils ne passeront pas’ — they will not pass.

Reinforcements were piled in — more grist to Von Falkenhayn’s mill. The deadly pattern was set that would prolong this battle from five days to more than 300 and increase the toll of casualties 14-fold.

However, the Germans were beginning to feel the pinch of their rapid advance. The fighting had been so fierce that they had lost as many men as the French — roughly 25,000 apiece at this point — and were losing momentum.

By getting ahead of themselves, they were also losing the protection of their biggest guns, left static at the rear and unable to be moved forward because the ground had been torn up. French counter-attacks, unhampered by artillery bombardment, were increasingly successful.

The battle now settled into trench warfare, the exchanging of mortar fire and a series of vicious encounters to secure vantage points in which machine gunners mowed down advancing enemy soldiers.

French pride got the better of military sense

Shellfire churned the battlefield into a muddy moonscape and sent men, cowering in trenches, mad.

A French sergeant recalled how during salvoes ‘the earth around us quaked and we were lifted and tossed about. The air was unbreathable. Our blinded and wounded soldiers kept falling on top of us and died while splashing us with their blood. It was a living hell. We were deafened, dizzy and sick at heart’.

On the other side, a German peeped over the rim of his trench ‘and all I can see is a wilderness’. He couldn’t stomach the stench of unburied corpses. Another longed for a Heimatschuss, a ‘blighty wound’ that would get him out of there and home. ‘Of my section, which consisted of 19 men, only three are left.’

Some deaths were even more pointless than others, the result of blunders. Deep inside the captured Fort Douaumont, German soldiers brewed up coffee on a table improvised from boxes of cordite, starting a fire which spread to a store of flame-thrower fuel and then to an ammunition magazine.

The chamber exploded, killing 679 men. With no hope of recovering the bodies from the fire, the area was sealed off and left.

A further 1,800 wounded managed to get away but some of these were shot by their own side as they fled from the fort. With their soot-blackened faces, they were mistaken for African troops fighting for the French.

The French tried to storm and recapture Douaumont but failed, at a cost of thousands of lives.

The Germans responded by assaulting Fort Vaux, another of the concrete strongholds, but the 600 French soldiers crammed inside held out in appalling conditions.

‘We lived in filth amid the smell of blood as 8,000 shells fell on the fort every day,’ said one defender.

For a whole week, men fought with machine-guns and flame-throwers in the fort’s pitch-black galleries, corridors and underground tunnels. The French garrison gave in only after they ran out of water and had resorted to drinking their own urine.

French soldiers pictured resting during their defence of Verdun. Prince Max of Baden, who as German Chancellor requested an armistice between Germany and the Allied powers, said the Verdun campaign 'ended in bitter disillusionment'

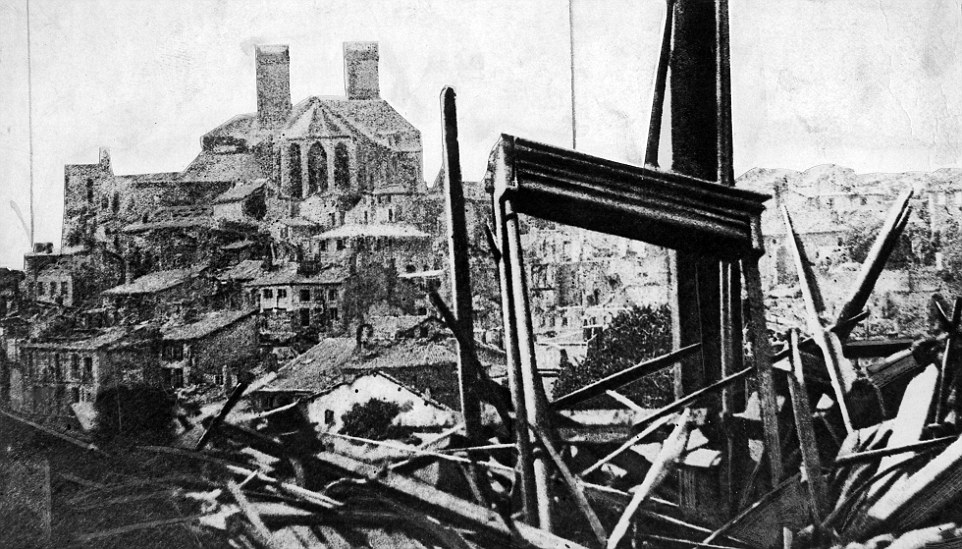

The martyred town: The ruined town and cathedral of Verdun. The city itself stands on the River Meuse, its citadel and cathedral looking out over the countryside, where the French had over the years built dozens of forts and concrete casements for artillery

The Germans took the fort, but their victory had cost them close to 2,750 casualties. The French then racked up 2,000 more dead and wounded in trying unsuccessfully to win it back.

By now, it was early June and, after four months of fighting, the Germans were on top.

French morale looked on the verge of collapse, despite cries from Petain to his fellow generals that ‘Verdun must not fall’.

Von Falkenhayn needed only to press home his advantage. But he could not. Germany was fighting on two fronts and, out of the blue, there were demands from the east, where the Russians were advancing and Germany was suddenly exposed. Troops were urgently needed there.

Fifty thousand were dispatched from the Western front and any attack to take Verdun and push on to Paris had to be put on ice.

The French seized on the lull to shore up their battered defences, and, as the end of June loomed, it was becoming clear that the German war machine was stalling.

They made one last effort to advance, preparing the way with a barrage of gas-filled shells.

Ground troops sliced through the French front line until those in the vanguard could see Verdun itself, just two miles away, shimmering in the July haze. But there was no momentum to continue and they were beaten back.

This would be as close as the Germans ever got to their goal. From that point on, the German army at Verdun went on the defensive, consolidating its positions and licking its considerable wounds.

In Berlin, the reality of the situation had to be faced.

French troops working with a mortar piece ion the battlefield. Prince Max of Baden later said of the battle: ‘We and our enemies had shed our best blood in streams and neither we nor they had come one step nearer to victory'

Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, Chief of the German General Staff, declared that ‘Verdun has exhausted our forces like an open wound. The enterprise has become hopeless’.

His chief of staff, General Erich Ludendorff, concluded that ‘Verdun was hell, a nightmare. Our losses were too heavy for us’.

There was to be no immediate withdrawal — that was not the German way — but it remained for the French to win back the territory they had lost.

Fort Douaumont was retaken on October 24, Fort Vaux ten days later, and the battle was finally declared over on December 18.

The French could claim the victory, and did. They had stopped the enemy, held their ground, stayed in the war and not fled as the Germans had intended.

But deadlock was the real result, with the emphasis on ‘dead’.

A century on, the cost in lives on both sides still takes the breath away. A quarter of a million men were dead and double that number wounded. And for what?

As Prince Max of Baden — who as German Chancellor requested an armistice between Germany and the Allied powers — said of the Verdun campaign: ‘It ended in bitter disillusionment.

‘We and our enemies had shed our best blood in streams and neither we nor they had come one step nearer to victory.’

www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3455565/Battle-bloody-men-called-MEAT-GRINDER-One-history-s-savage-sieges-began-hail-shots-century-ago-left-250-000-dead-achieved-NOTHING.html#ixzz40mdIO3