John Hilly

Respected Leader

That Time Chechen Rebels Floated Into Combat on Inner Tubes

Militants crossed the frigid Sunzha River to ambush Russian tanks

by ROBERT BECKHUSEN

The First Chechen War of 1994–1996 was a disaster for the Russian army, manned by poorly-trained conscripts with inadequate tactics and logistics. Chechen rebels, skilled in mountain warfare, would force a Russian withdrawal — although a revamped Russian military would come back, prepared, in 1999.

The Russian army in the mid-’90s also fought linearly, wasting lives in head-on attacks against prepared Chechen defenses. But the Russian army often had the advantage in weapons, particularly tanks, and on many occasions the Chechens could do little about it.

So the Chechens got creative. During one skirmish in the first war, Chechen rebels with rocket-propelled grenade launchers tried to defeat a Russian tank force by floating toward it on inner tubes.

This anecdote comes from the interesting book Fangs of the Lone Wolf by Dodge Billingsley and Lester Grau. The authors based the book on interviews with Chechen veterans of the region’s two wars with Russia, and was helpfully published by the U.S. Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office, so it’s available in its entirety via PDF on the FMSO’s website.

Fangs of the Lone Wolf analyzes a series of tactical vignettes — maps included — during the Chechen wars, and is useful for students of the conflict and those interested in detailed small unit tactics.

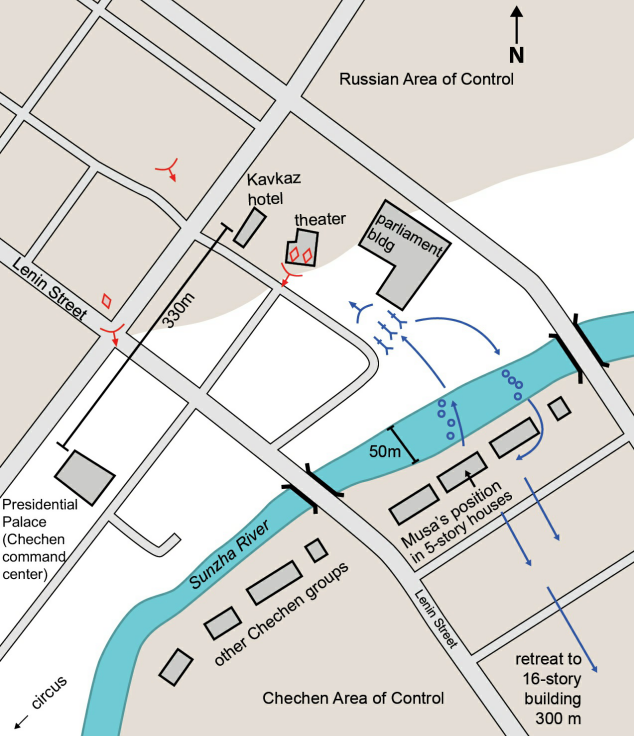

Musa’s attack. Illustration via ‘Fangs of the Lone Wolf’

One Chechen veteran named Musa — his identity kept secret due to concerns of reprisal — recalled his experiences during the Battle of Grozny in January 1995. The Russian army had advanced slowly toward the presidential palace and the Sunzha River, which cuts the city in northern and southern halves.

The Chechen rebels were still in control of the palace, part of a bridgehead on the northern side of the river, but had pulled most of their forces back to the southern side.

Chechen warlord Aslan Maskhadov had set up his command center in the presidential palace, but at this point it was a largely symbolic target — the real strategic points were high- and mid-rise apartment blocks useful for snipers and scouts. Militants occupied several of these buildings on the southern bank of the river, and they made formidable strongpoints.

Still, in war, symbolism — and its morale and propaganda value — is important, so the Russian army brought up tanks to shell Maskhadov’s headquarters. The Russians also took the devastated urban terrain into account, backing up two tanks into a smashed-up theater around 330 meters away.

Basically, the theater was a giant bunker that shielded the tanks from attack. Complicating matters further for the Chechens, Russian infantry were defending the theater and would shoot any Chechen fighters who came close. And the two nearest bridges across the Sunzha were too exposed to cross by foot.

So Musa and seven of his fighters, half of his force, crossed the river at night on inner tubes — inflated car tires, actually — while loaded down with their weapons … in January.

Billingsley and Grau wrote:

“The Russians would never suspect us getting across the river this way.” [Musa said.] Knowing that his men were covering their slow and arduous crossing gave Musa a feeling of confidence. They reached the north bank and checked their gear. They were obviously cold and wet as they set out on foot toward the Russian tank position. The route was strewn with rubble, including debris from the Parliament building.Musa guessed they made it to within fifty meters of the Russian tanks. They opened fire but quickly came under Russian return fire. Musa did not even notice the cold. A Chechen RPG struck the closest tank, setting it on fire, but they could not get a clear shot at the second tank. Several rounds missed. Out of RPG ammunition and under increasing small arms fire from the Russian infantry guarding the position, Musa shot a flare into the air signaling his retreat.

The flare was the signal for the other half of Musa’s force — in the apartments on the south side of the river — to open fire and cover the attacking force’s retreat.

Musa’s team dived into the river and floated back in their inner tubes, not noticing the cold because of the adrenaline high of combat until they reached a friendly building. A fire warmed them up — then they crashed.

Was it a victory for the rebels? Well, kinda. There were a lot of little clashes like this. And many accounts of “successful” Chechen ambushes and attacks recounted in Fangs of the Lone Wolf were often only partial successes, reflecting the inherent asymmetry of the conflict.

Even in victory, one rarely destroys an entire enemy force. In this case, the attacking Chechens were lucky to have taken out a single tank, let alone escape with no loss of life among their own.

But regardless, the Chechen separatists were unable to prevent the fall of the presidential palace, although the rebels would go on to win the war. Then they would lose the second one, three years later, at the hands of a Russian army that learned from its mistakes.

https://warisboring.com/that-time-c...combat-on-inner-tubes-ee053c708cf7#.5oaatl3bu