Talebaanithan muuttivat taktiikkansa aikoja sitten sellaiseksi etteivät keräänny hirveässä lössissä yhteen paikkaan, vaan lähinnä toimivat 10-20 ukkelin soluina joita sitten yhdistellään tarpeen vaatiessa kun hyökätään, joten miksi olisivat nyt tavanneet tuollaisella joukolla (kaikki vieläpä johtajia) yhdessä rakennuksessa?

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Afganistan

- Viestiketjun aloittaja Teräsmies

- Aloitus PVM

-

- Tagit

- afganistan

Talebaanithan muuttivat taktiikkansa aikoja sitten sellaiseksi etteivät keräänny hirveässä lössissä yhteen paikkaan, vaan lähinnä toimivat 10-20 ukkelin soluina joita sitten yhdistellään tarpeen vaatiessa kun hyökätään, joten miksi olisivat nyt tavanneet tuollaisella joukolla (kaikki vieläpä johtajia) yhdessä rakennuksessa?

Kun noin paljon tappioita kärsinyttä organisaatiota aletaan uudelleenorganisoimaan, niin auttaa huomattavasti jos johtajat ovat kaikki läsnä käskynjaossa. Ja olisiko niin, että arabi tyyliin jotajat pyrkivät välttämään vaaraa, joten johtajat ovat viimeisiä jotka menetetään.

D

Deleted member 1381

Guest

Talebaanithan muuttivat taktiikkansa aikoja sitten sellaiseksi etteivät keräänny hirveässä lössissä yhteen paikkaan, vaan lähinnä toimivat 10-20 ukkelin soluina joita sitten yhdistellään tarpeen vaatiessa kun hyökätään, joten miksi olisivat nyt tavanneet tuollaisella joukolla (kaikki vieläpä johtajia) yhdessä rakennuksessa?

Tuolla on tapana päättää asioita shurassa, eli islamilaisen perinteen mukaisessa kokouksessa. Päälliköiden arvovalta ei taida antaa myöten olla osallistumatta ja noudattaa vain muiden päättämiä käskyjä. Tuohon kun lisää sen, ettei taliban ole täysin yhtenäinen organisaatio, vaan noissa kokouksissa voi olla useamman ryhmittymän tai heimon johtajia, niin meneehän siinä porukkaa kerralla. Eli siellä on voinut mennä esimerkiksi jonkin heimon johtajia, jotka ovat tehneet määräaikaisen sopimuksen talibanin kanssa.

Falangi

Kenraali

Tjaah, jos ne ovat valvoneet kohdetta lennok(e)illa reaaliaikaisesti ja laskeneet että rakennukseen on mennyt se 50(+) ukkoa sisään ennen iskua, joka videon perusteella tuhoaa rakennuksen aika täydellisesti, niin voihan se olla tottakin että sellainen määrä kuoli.Taitaa oikeampi kaatomäärä tulla kun jaetaan jenkkien ilmoitus kymmenellä eli 5-7 kuollutta...

Toinen asia onkin sitte se, että miten tiedetään varmuudella kuinka moni noista oli nimenomaan (talebanin) johtajia eikä muuta sakkia..

Tjaah, jos ne ovat valvoneet kohdetta lennok(e)illa reaaliaikaisesti ja laskeneet että rakennukseen on mennyt se 50(+) ukkoa sisään ennen iskua, joka videon perusteella tuhoaa rakennuksen aika täydellisesti, niin voihan se olla tottakin että sellainen määrä kuoli.

Toinen asia onkin sitte se, että miten tiedetään varmuudella kuinka moni noista oli nimenomaan (talebanin) johtajia eikä muuta sakkia..

No, tuossa aikaisemmin oli selitys miten nuo shurat toimivat, joten kuinka paljon muuta sakkia sinne sallittaisiin jo ihan salassapidon takia? Voi olla, että jokaisella johtajalla saattaisi olla oma "hovi" mukana, mutta käytännön kannalta nekin ovat varsin tärkeää sakkia, jos ne saadaan pomon ohessa.

Taliban tappoi 30 afgaanisotilasta – tulitauon päättymisestä vain kolme päivää

https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10264988Ääriliike Taliban on tappanut kolmekymmentä Afganistanin joukkojen sotilasta. Hyökkäys kohdistui kahdelle armeijan tarkastuspisteelle Afganistanin länsiosassa Badghiksen alueella.

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/talibans-best-fighters-being-trained-by-iran-bbzc68n3m

Hundreds of Taliban fighters are receiving advanced training from special forces at military academies in Iran as part of a significant escalation of support for the insurgents, Taliban and Afghan officials have told The Times.

The scale, quality and length of the training is unprecedented and marks not only a shift in the proxy conflict between the US and Iran inside Afghanistan, but also a potential change in Iran’s ability and will to affect the outcome of the Afghan war.

Hundreds of Taliban fighters are receiving advanced training from special forces at military academies in Iran as part of a significant escalation of support for the insurgents, Taliban and Afghan officials have told The Times.

The scale, quality and length of the training is unprecedented and marks not only a shift in the proxy conflict between the US and Iran inside Afghanistan, but also a potential change in Iran’s ability and will to affect the outcome of the Afghan war.

Deh Balan ilmoitetaan kukistuneen.

Isisin Afganistanin pääkaupunki luhistui jättioperaation jälkeen - jihadisteja kuoli 167, USA:n ja Afganistanin erikoisjoukkoja 0

Tänään klo 17:46

Deh Balan kaupunki Pakistanin rajalla oli Isisille äärimmäisen tärkeä tukikohta terroristien rahoituksen ja logistiikan kannalta.

Irakin Mosul - heinäkuu 2017. Syyrian Raqqa -lokakuu 2017. Afganiastnin Deh Bala - heinäkuu 2018. Äärijärjestö Isisin "pääkaupungit" eri maissa käyvät vähiin.

Uutistoimisto Reuters kertoo, että operaatiossa kuoli 167 jihadistia. Amerikkalaisia ja afganistanilaisia sotilaita ei kaatunut yhtäkään.Lisäksi Isis kärsi huomattavia kalustotappiota.

Alueelle tiputettiin MOAB

Operaatio oli pitkälti ohi jo kesäkuun alkupuolella, mutta everstiluutnantti Josh Thielin mukaan miinanraivausoperaatio on yhä käynnissä.

- Tämä oli tärkeimmistä turva-alueista, millä oli kaksi tarkoitusta. Ensinnäkin se mahdollisti Isisin rahoituksen ja logistiikan ja nyt olemme riistäneet ne heiltä. Toisekseen, Isis käytti paikkaa valmistellakseen suuria hyökkäyksiä Kabuliin ja Jalalabadiin, Thiel sanoo Reutersill

Alue on ollut Yhdysvaltain johtaman liittouman tähtäimessä aiemminkin. Yhdysvaltain armeija pudotti huhtikuussa 2017 läheiselle Aachinin alueelle jättiläismäisen GBU-43/B -pommin.

Pommilla hätistettiin terroristit pois tunneli- ja luolaverkostoistaan.

U.S. soldier killed in Afghanistan was part of CIA operation

By WESLEY MORGAN

07/24/2018 07:12 PM EDT

An Army Ranger who was killed in Afghanistan earlier this month was part of a secret program that helps the CIA hunt down militant leaders, according to three former special operations soldiers who knew him.

Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Celiz, 32, a longtime member of the 1st Battalion of 75th Ranger Regiment, died on July 12 “of wounds sustained as a result of enemy small arms fire” in eastern Afghanistan’s Paktiya province, the Army announced the next day.

But he was part of a team of Army Rangers supporting the CIA in an intensifying effort to kill or capture top militant targets, even as the broader U.S. military mission focuses on training and advising Afghan security forces.

“They’re pretty active to say the least,” said a former special operations officer with detailed knowledge of the program, which previously went by the code name Omega and now goes by ANSOF. “They’re the main effort out there in terms of frequency of missions right now.”

He, like others, spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss classified operations.

The Pentagon reports there are 15,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan — some of them part of a NATO-led mission supporting the Afghan government and the rest part of a separate U.S. mission conducting counterterrorism raids.

Under both of those mandates, U.S. troops try to let the Afghan military units plan their own operations and conduct them with minimal American help.

But the CIA has always run its own separate counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan from a headquarters in Kabul and a string of bases in border provinces. And since the early months of the Afghan war, the military has loaned small numbers of special operations troops to the agency under the Omega program.

Over the past year, the CIA has ramped up its activities in Afghanistan at the behest of the Trump administration, according to a report in The New York Times, including by expanding its target set to encompass members of regional militant groups like the Taliban, which were long the purview of the military — not just foreign terrorist groups like al-Qaida.

The CIA declined to comment, and the military does not officially acknowledge that it attaches personnel to the CIA.

“There are certain personnel and units that, due to classification, we do not discuss,” said Lt. Col. Robert Bockholt, a spokesman for U.S. Army Special Operations Command, the Rangers’ parent organization.

But the Rangers, who lead the military’s counterterrorism task force in Afghanistan, have for years loaned a small number of their most experienced personnel to the CIA to provide helicopter gunships, drones and medical evacuations. Earlier in the war, the Navy’s SEAL Team 6 supplied the bulk of the military personnel to support the for the CIA operations.

“The agency’s got a targeting list separate from the JSOC task force’s,” said a former special operations officer, referring to the Joint Special Operations Command, the military counterterrorism headquarters that oversees most Ranger missions in Afghanistan. “Sometimes it’s the same targets on both lists, sometimes not.”

“The agency uses its Afghans to kill or capture guys off their target list,” he explained. The CIA’s Afghan surrogates “are doing the assaulting and the killing and the capturing,” he added, but the Rangers “are out there with them.”

“The Rangers who get selected for that mission, to support our interagency partners, are typically the most calm, collected, mature, and professional of an elite group,” said an active-duty military officer with detailed knowledge of the program who also knew Celiz.

Describing the types of support the Rangers provide to the CIA teams, the officer added: “It’s mainly about medical and fire support — the things that our guys are just far better prepared for than theirs.”

It’s unclear which militant group or leader was the target of the mission on which Celiz was killed, but like the military, the CIA is also now targeting members of the Afghan affiliate of the Islamic State, according to the Times.

According to a former Ranger who served in the same unit, Celiz was shot while helping to evacuate a wounded Afghan commando, who later also died.

The U.S. military statement announcing Celiz’s death acknowledged that he was “conducting operations in support of a medical evacuation landing zone” when he was shot, but said nothing about who was being evacuated or about additional casualties.

An official Army biography of Celiz lists him as a mortar platoon sergeant in his Ranger battalion. He was on his fifth deployment with the Rangers after transferring in from the regular Army.

In a statement, Col. Brandon Tegtmeier, commander of the 75th Ranger Regiment, called Celiz a “national treasure."

The former Ranger who previously served in same unit as Celiz called him the “hardest worker in the battalion.”

“Celiz was a top-notch dude,” agreed the former special operations officer who served with him. “I can’t say enough good things about him. He didn’t talk a whole lot but he was always happy. No matter how bad things sucked, he always had a dumb smile on his face and it drove guys crazy.”

"We called him the Silver Fox," said another former Ranger who worked closely with Celiz, a reference to his gray hair and advanced age for a member of the unit. "He was one of the humblest men I ever met. Where others would fall apart, you could lean on him to pull through."

Ei ihan tuore artikkeli eli on voinut olla täällä.

A Funeral of 2 Friends: C.I.A. Deaths Rise in Secret Afghan War

A Funeral of 2 Friends: C.I.A. Deaths Rise in Secret Afghan War

The number of C.I.A. deaths in Afghanistan rivals those killed in the Southeast Asia conflicts of nearly a half-century ago.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/06/world/asia/cia-afghanistan-war.html#click=https://t.co/wFl4k7jJoZSept. 6, 2017

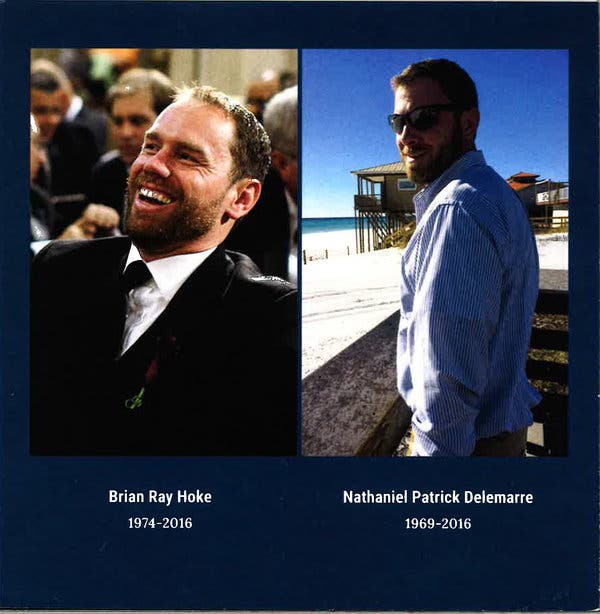

WASHINGTON — On a sweltering day earlier this summer, operatives with the Central Intelligence Agency gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to bury two of their own. Brian Ray Hoke and Nathaniel Patrick Delemarre, elite gunslingers who worked for the C.I.A.’s paramilitary force, were laid to rest after a firefight with Islamic State militants near Jalalabad in Afghanistan, close to the border with Pakistan.

There had been scant mention of Mr. Hoke’s death in local news reports in Leesburg, Va., his home, and nothing at all about Mr. Delemarre in news accounts in the Florida Panhandle, where his family lives. Their deaths this past October were never acknowledged by the C.I.A., beyond two memorial stars chiseled in a marble wall at the agency’s headquarters in Langley, Va.

Today there are at least 18 stars on that wall representing the number of C.I.A. personnel killed in Afghanistan — a tally that has not been previously reported, and one that rivals the number of C.I.A. operatives killed in the wars in Vietnam and Laos nearly a half century ago.

The deaths are a reflection of the heavy price the agency has paid in a secret, nearly 16-year-old war, where thousands of C.I.A. operatives have served since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The deaths of Mr. Hoke, 42, and Mr. Delemarre, 47, show how the C.I.A. continues to move from traditional espionage to the front lines, and underscore the pressure the agency faces now that President Trump has pledged to keep the United States in Afghanistan with no end in sight.

“We are going to be fighting this war for a very long time,” said Ken Stiles, a former C.I.A. counterterrorism analyst who worked closely with paramilitary officers in Afghanistan and who lost three friends in the war.

The Makings of Secret Gunslingers

Mr. Hoke grew up in South Dakota, played violin and football in high school, graduated from the United States Naval Academy with a degree in oceanography and in 1997 passed the grueling test to become a member of the Navy SEALs. He was deployed to the Middle East and Europe, and in 2004 joined the C.I.A.

A page from the funeral program for Mr. Hoke and Nate Delemarre, C.I.A. operatives who were killed in Afghanistan in October 2016.

At the agency’s training facility in Virginia, known as the Farm, Mr. Hoke learned how to recruit and handle spies and the art of crafting secret messages. He stood out, a classmate recalled, as among the best in the class. Mr. Hoke moved on to the agency’s advanced training course, held at a secret location in the southeastern United States, and was soon part of the agency’s paramilitary arm, the Special Activities Division.

Like Mr. Hoke, many of those in the Special Activities Division came from the SEALs, the Army’s Delta Force and other elite military units.

During his 12 years in the C.I.A., Mr. Hoke played the role of both commando and spy. He deployed to Iraq and other hot spots but also posed as a foreign service officer — the agency’s typical cover for a covert officer — in Greece and Denmark. The agency had Mr. Hoke serve outside war zones to broaden his experiences, friends said.

Mr. Hoke, like his colleagues, knew there were great risks. In a desk drawer at home in Leesburg, he kept a clipping of a newspaper article about another C.I.A. operative, Maj. Douglas A. Zembiec, a Marine officer and fellow Naval Academy graduate known as the “Lion of Falluja,” who was killed in Iraq in 2007.

In 2008, Mr. Hoke was deployed in Afghanistan when he was called on to reinforce a group of C.I.A. operatives who had been ambushed by the Taliban. One of the operatives, Donald Barger, 40, a former Ranger and Green Beret who earned the Bronze Star, was dead by the time Mr. Hoke arrived at the scene, former agency officers said.

Friends say that Mr. Hoke turned to painting to help decompress after his tours.

In an email exchange, Mr. Hoke’s wife, Christy, described her husband as “the kind of person movies are made about, as are most of his colleagues. Unbelievable human beings.”

George A. Whitney, 38, center, who was killed in December in the Jalalabad area of Afghanistan.

“He lived by a code that I will not break for anything. Even writing this email feels like a small betrayal,” she said.

Mr. Hoke left behind three children.

Little is known about Mr. Delemarre’s service in the C.I.A. According to military records, he spent roughly a dozen years as a radio operator in the Marine Reserves, where he was a lance corporal. Friends willing to talk about him said he joined the C.I.A. after the Sept. 11 attacks and later shifted to the Navy Reserves — a commitment he maintained while also working at the spy agency — where he became a commissioned officer.

Mr. Delemarre’s wife declined to be interviewed. He left behind two daughters.

The C.I.A. in Afghanistan

Since 2001, as thousands of C.I.A. officers and contractors have cycled in and out of Afghanistan targeting terrorists and running sources, operatives from the Special Activities Division have been part of some of the most dangerous missions. Over all, the division numbers in the low hundreds and also operates in Somalia, Iraq, the Philippines and other areas of conflict.

C.I.A. paramilitary officers from the division were the first Americans in Afghanistan after the Sept. 11 attacks, and they later spirited Hamid Karzai, the future president, into the country. Greg Vogle, an agency operative who took Mr. Karzai into Afghanistan, went on to run the paramilitary division and became the top spy at the C.I.A.

The first American killed in the country, Johnny Micheal Spann, was a C.I.A. officer assigned to the Special Activities Division. He died in November 2001 during a prison uprising.

In the years since, paramilitary officers from the Special Activities Division have trained and advised a small army of Afghan militias known as counterterrorism pursuit teams. The militias took on greater importance under President Barack Obama, who embraced covert operations because of their small footprint and deniability.

The militias, and their C.I.A. handlers, were at times accused by Afghan officials and others of acting as a law unto themselves, running roughshod over civilians and killing innocents. Raids by C.I.A. paramilitary officers and militia fighters also resulted in airstrikes that killed Afghan civilians.

In 2009, in the worst loss for the agency in Afghanistan, a suicide bomber detonated an explosives vest and killed seven C.I.A. employees — none were from the Special Activities Division — at a forward operating base in Khost, on the Pakistan border.

At the same time, the C.I.A. helped build the Afghan intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security, which has long faced accusations of torturing suspected militants.

The C.I.A. also spent more than a decade financing a slush fund for Mr. Karzai. Every month, agency officers would drop off cash in suitcases, backpacks and even plastic shopping bags. Mr. Karzai’s aides would use the cash to run a vast patronage network, paying off warlords, lawmakers and others they wanted to keep on their side.

The slush fund, which was exposed in 2013, was seen by many American diplomats and other officials and experts as fueling the rampant corruption that has undermined the American effort to build a functioning democracy in Afghanistan.

An Assault and a Funeral of Two Friends

On Oct. 21, 2016, Mr. Hoke and Mr. Delemarre were shot in an assault on an Islamic State compound in Jalalabad, where the militant group has made inroads in recent years.

Flags lined the streets of Mr. Hoke’s neighborhood in Leesburg, Va., last October.Hannah Dellinger/Loudoun Times-Mirror

Details are sparse. Friends say that as Mr. Hoke made his way around a wall, a militant shot him. Mr. Hoke radioed that he was down, Mr. Delemarre heard his close friend’s voice, left his position of safety and ran to Mr. Hoke’s aid, but Mr. Hoke soon died. Mr. Delemarre was wounded in his attempt to help and was evacuated to Germany, where he died shortly after his wife arrived.

The two were awarded stars at the C.I.A. in May, when the agency held its annual memorial for officers who died in the line of duty. A third C.I.A. paramilitary officer, George A. Whitney, 38, who was killed in December in the Jalalabad area, also received a star. As a Marine captain, Mr. Whitney served with the Third Marine Reconnaissance Battalion in Anbar province in Iraq. Relatives of Mr. Whitney, who studied classics and played fullback on the football team at Bates College in Maine, declined to comment.

Other C.I.A. operatives killed in Afghanistan since 2001 include Dario Lorenzetti, a West Point graduate and former Ranger, who died in 2012 after a member of the Afghan intelligence service detonated a suicide vest in an insider attack; Jay Henigan, 61, a contractor and plumber who was gunned down in Kabul in 2011 during an attack; a pair of paramilitary officers killed in 2003 while tracking terrorists in southeastern Afghanistan; and Nathan Ross Chapman, a Green Beret who was detailed to a C.I.A. paramilitary team in Afghanistan when he was shot to death hunting Al Qaeda in January 2002.

The seven C.I.A. employees killed by a suicide bomber in 2009 in Khost were at Forward Operating Base Chapman, which had been named for him.

The ranks of C.I.A. operatives aren’t easily replaced, said Mr. Stiles, the former counterterrorism analyst.

“That’s going to be one of the challenges for the government,” he said. “How do we maintain the level of experience and expertise in a war that is going to last for another 20 or 30 years or longer?”

At the Arlington funeral of Mr. Hoke and Mr. Delemarre on July 14 — long delays before interment are common — heavily muscled men with beards and sunglasses sweated through their suit jackets as a Navy honor guard played taps and performed a rifle salute. Mr. Vogle, the C.I.A. operative who took Mr. Karzai into Afghanistan, stood among the mourners.

A program from the service shows a smiling Mr. Hoke in a tuxedo and a grinning Mr. Delemarre on the beach. On the back of the program is a quote from Adm. Chester W. Nimitz: “They fought together as brothers in arms; they died together and now they sleep side by side.”

Correction: September 8, 2017

Because of an editing error, an article on Thursday about deaths of C.I.A. paramilitary operatives in Afghanistan referred incorrectly to the location where Brian R. Hoke, one of the operatives killed, grew up. As the article correctly noted, he grew up in South Dakota, but not in the town of Park River. (The specific location in South Dakota where he lived has not been confirmed.)

John Hilly

Respected Leader

Aikamoinen laukaus!

Tarkka-ampuja tappoi ISIS-johtajan 2,5 kilometrin päästä

Matti Lepistö | 12.08.2018 | 23:55- päivitetty 12.08.2018 | 23:57

Aseena käytettiin .50 kaliiperin konekivääriä.

Daily Star kertoo, että Britannian SAS-erikoisjoukkojen tarkka-ampuja surmasi lähes 2,5 kilometrin päästä ISIS-johtajan Afganistanissa. Kyseessä on tiettävästi pisin etäisyys, josta brittien eliittijoukkojen sotilas on tehnyt kuolettavan laukauksen.

Tarkka-ampuja onnistui tappamaan terroristin yhdellä laukauksella. Luoti osui ISIS-komentajan rintaan ja tappoi hänet välittömästi.

Ampuminen tapahtui kesäkuussa ISIS:n hallitsemalla alueella Afganistanin pohjoisosissa. Salaisella operaatiolla olleet sotilaat seurasivat pitkän etäisyyden päästä ISIS:n tukikohtaa, johon Britannian ja USA:n tappolistalla oleva terroristikomentaja ilmaantui.

Tavallisen tarkkuuskiväärin sijaan aseena käytettiin yli 40 vuotta vanhaa .50 kaliiperin Brownin M -konekivääriä, johon kiinnitettiin tehokas tähtäin.

– Tarkka-ampuja tiesi, että hänellä on vain yksi mahdollisuus. Luodin matkaan meni muutamia sekunteja, jonka jälkeen komentaja näytti repeytyvän palasiksi, sotilaslähde kertoo.

Daily Starin mukaan ase on toimitettu SAS-erikoisjoukkojen päämajaan muistoksi ennätyslaukauksesta.

https://www.verkkouutiset.fi/tarkka-ampuja-tappoi-isis-johtajan-25-kilometrin-paasta/

Tarkka-ampuja tappoi ISIS-johtajan 2,5 kilometrin päästä

Matti Lepistö | 12.08.2018 | 23:55- päivitetty 12.08.2018 | 23:57

Aseena käytettiin .50 kaliiperin konekivääriä.

Daily Star kertoo, että Britannian SAS-erikoisjoukkojen tarkka-ampuja surmasi lähes 2,5 kilometrin päästä ISIS-johtajan Afganistanissa. Kyseessä on tiettävästi pisin etäisyys, josta brittien eliittijoukkojen sotilas on tehnyt kuolettavan laukauksen.

Tarkka-ampuja onnistui tappamaan terroristin yhdellä laukauksella. Luoti osui ISIS-komentajan rintaan ja tappoi hänet välittömästi.

Ampuminen tapahtui kesäkuussa ISIS:n hallitsemalla alueella Afganistanin pohjoisosissa. Salaisella operaatiolla olleet sotilaat seurasivat pitkän etäisyyden päästä ISIS:n tukikohtaa, johon Britannian ja USA:n tappolistalla oleva terroristikomentaja ilmaantui.

Tavallisen tarkkuuskiväärin sijaan aseena käytettiin yli 40 vuotta vanhaa .50 kaliiperin Brownin M -konekivääriä, johon kiinnitettiin tehokas tähtäin.

– Tarkka-ampuja tiesi, että hänellä on vain yksi mahdollisuus. Luodin matkaan meni muutamia sekunteja, jonka jälkeen komentaja näytti repeytyvän palasiksi, sotilaslähde kertoo.

Daily Starin mukaan ase on toimitettu SAS-erikoisjoukkojen päämajaan muistoksi ennätyslaukauksesta.

SAS sniper guns down ISIS commander 'from nearly 1.5 miles away' in Afghanistan https://t.co/pw3vaCvICh pic.twitter.com/rd2khKCvLY

— Daily Mirror (@DailyMirror) August 12, 2018

— Daily Mirror (@DailyMirror) August 12, 2018

https://www.verkkouutiset.fi/tarkka-ampuja-tappoi-isis-johtajan-25-kilometrin-paasta/

Mistähän on peräisin Verkkouutisten "Brown M konekivääri", ei ainakaan siteeratusta uutisesta. Uutiset näyttävät kertovan, että "kill" tapahtui ajoneuvoon asennetulla Browning M1 kk:lla. Ampumamatka oli lähes 2400 m, ei yli 2,5 km. Pidemmältäkin on osuttu eli ei mikään ennätys, kuten Verkkouutisissa on jo kommentoitu. Hyvä suoritus silti! Autolla pääsivät karkuunkin.

Falangi

Kenraali

Onhan se siinä mielessä ennätys, että se taisi olla pisin kk:lla suoritettu tappo.Mistähän on peräisin Verkkouutisten "Brown M konekivääri", ei ainakaan siteeratusta uutisesta. Uutiset näyttävät kertovan, että "kill" tapahtui ajoneuvoon asennetulla Browning M1 kk:lla. Ampumamatka oli lähes 2400 m, ei yli 2,5 km. Pidemmältäkin on osuttu eli ei mikään ennätys, kuten Verkkouutisissa on jo kommentoitu. Hyvä suoritus silti! Autolla pääsivät karkuunkin.

Vietnamin sodassa entinen ennätyksen haltija amerikkalainen Carlos Hathcock harrasti samaa, kun ei vielä ollut käytössä .50 cal tarkkuuskiväärejä.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Hathcock

In 1967, Hathcock set the record for the longest sniper kill. He used an M2 .50 Cal Browning machine gun mounted with a telescopic sight at a range of 2,500 yd (2,286 m), killing a Vietcong guerrilla.[38] In 2002, this record was broken by Canadian snipers (Rob Furlong and Arron Perry) from the third battalion of Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry during the War in Afghanistan. Hathcock was one of several individuals to utilize the M2 Browning machine gun in the sniping role. This success led to the adoption of the .50 BMG cartridge as a viable sniper round. Sniper rifles have since been designed around and chambered in this caliber since the 1970s.

https://sputniknews.com/world/201808271067495493-afghanistan-tajikistan-russia-plane-taliban/

Nyrkin heilutusta sille joka itkee uutislähteestä.

Nyrkin heilutusta sille joka itkee uutislähteestä.

http://tass.com/defense/1018368Russia has recorded flights of unidentified helicopters delivering weapons to the Taliban (a movement outlawed in Russia) and the Islamic State (a terror group outlawed in Russia) units active in Afghanistan, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said at a briefing on Thursday.

“We would like to once again point to the flights of unidentified helicopters in northern Afghanistan, which deliver weapons and ammunition to local ISIL [the former name of the Islamic State group – TASS] units and Taliban members cooperating with the group. In particular, the Afghan media and local residents say that such helicopters were seen in the Sar-e Pol Province,” the Russian diplomat said.

“This is happening in close proximity to the borders of Central Asian states, while many of the IS militants active in Afghanistan come from those countries,” Zakharova pointed out.

The Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman also said that the Afghan security agencies, as well as the Command of US and NATO troops in Afghanistan, did not react to those helicopter flights. “In this regard, the question arises – who is behind these flights, who provides weapons to the terrorists and secretly creates springboards for them near the southern borders of the CIS and why is it happening at all, given NATO’s actual control of Afghanistan’s airspace,” Zakharova said.

Aseita sisään ja huumeita ulos?

Venäjä se vaan vastaa Ukrainalle lähetettyihin Javelineihin.

Kiinalaiset rakentavat pienehköä tukikohtaa Afganistaniin.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/08/29/china-building-military-base-afghanistan/The base will be only the second overseas site for the increasingly active Chinese military, coming a year after a base was opened in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa.

Around 500 troops will be stationed in the base training their Afghan counterparts in the remote Wakhan Corridor in the north east province of Badakhshan, the South China Morning Post reported.

The report, which was denied by the Chinese government, said work had already begun at the site.

Kertauksena:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-43500299

"Russia is supporting and even supplying arms to the Taliban, the head of US forces in Afghanistan has told the BBC."

ISIS olisi loogista jatkumoa tälle ja jos kerran Venäjän informaatiokoneisto on käsketty vihjailemaan, että länsi aseistaa ISIS:stä Afganistanissa, olisi se lähes varma todennus sille, että Venäjä itse tukee ISIS:stä Afganistanissa.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-43500299

"Russia is supporting and even supplying arms to the Taliban, the head of US forces in Afghanistan has told the BBC."

ISIS olisi loogista jatkumoa tälle ja jos kerran Venäjän informaatiokoneisto on käsketty vihjailemaan, että länsi aseistaa ISIS:stä Afganistanissa, olisi se lähes varma todennus sille, että Venäjä itse tukee ISIS:stä Afganistanissa.

Super Hercules tullut tonttiin ja 11 kuollut.

https://sputniknews.com/asia/201810031068556975-super-hercules-crash-afghanistan/

Pahoittelut taas Sputnik uutisesta mutta kun mikään muu ei ole vielä reagoinut uutiseen.

https://sputniknews.com/asia/201810031068556975-super-hercules-crash-afghanistan/

Pahoittelut taas Sputnik uutisesta mutta kun mikään muu ei ole vielä reagoinut uutiseen.