Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Cyber-ketju: verkkovakoilu,kännyköiden ja wlanien seuranta, hakkerointi, virukset, DoS etc

- Viestiketjun aloittaja OldSkool

- Aloitus PVM

morice

Alikersantti

Tälläinen ketju tuli vastaan.

Tutkimusta teki:

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Artikkeli:

www.newyorker.com

www.newyorker.com

Tutkimusta teki:

Citizen Lab - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Artikkeli:

How Democracies Spy on Their Citizens

The inside story of the world’s most notorious commercial spyware and the big tech companies waging war against it.

Boris Johnson should “pay close attention” to basic rules of cybersecurity, a former national security adviser has said, after it emerged that the United Arab Emirates was accused of hacking into a mobile phone at Downing Street.

Peter Ricketts, who held the post between 2010 and 2012, said the cyber-attack demonstrated that “commercially made” Pegasus software from NSO Group allowed a “wide range of actors” to engage in sophisticated espionage.

Anybody with access to secret information needed to be aware of the fast-changing risk, the peer added, including the prime minister, who was forced to change his mobile number last year after it emerged it had been available online.

“It’s vital that anyone with access to sensitive material up to and including the PM have to pay close attention to the basic rules of cybersecurity, including their phone numbers,” Ricketts said.

Johnson was forced to suddenly change his mobile phone last spring after it emerged that his number had been available online for 15 years. It was published on a thinktank press release from 2006 and never deleted.

Pegasus is sophisticated software, made by the Israeli company NSO Group, that can covertly take control of a person’s mobile phone, take and copy data from it and even turn it into a remote listening device without their permission. But for it to be effective, it needs to be given a phone number to target.

NSO Group said the allegations were “wrong and misleading” and the company denied involvement. “For technological, contractual and legal reasons, the described allegations are impossible and have no relation to NSO’s products,” the company said.

On Monday, Citizen Lab, a group of technology researchers based at Toronto University, said they had uncovered evidence of “multiple suspected instances of Pegasus spyware infections” within official UK networks including Downing Street and the Foreign Office.

Using digital forensic techniques developed over several years, the researchers said they concluded the attack on Downing Street was “associated with a Pegasus operator we link to the UAE”, and took place on 7 July 2020.

There is no firm evidence as to why the UAE may have wanted to target Downing Street on that date. However, a day earlier the British government announced a range of economic sanctions targeting 20 Saudi nationals accused of being involved in the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, plus individuals from Russia, Myanmar and North Korea. Neighbouring UAE is a close ally of Saudi Arabia.

The UAE ambassador to London, Mansoor Abulhoul, denied reports that the UAE may have used spyware to hack into either Downing Street or the Foreign Office.

He said: “These reports are totally baseless and we reject them. The UK is one of the UAE’s closest and dearest allies and we would never do such a thing to them.”

He added he was shocked that the allegations had even been made, pointing to the recent enhancement of relations between the two countries, including a growing economic partnership.

The denial is a reflection of the importance that the UAE attaches to the relationship, and the potential damage the espionage allegation could cause if it were given credence.

One Citizen Lab researcher told the New Yorker, which first reported on the story, that it believed some data may have been stolen from Downing Street by the hackers. But the research group said it could not identify whether Johnson’s own phone or that of any other named official was targeted.

The Foreign Office declined to discuss the story, saying: “We do not routinely comment on security matters.” But Citizen Lab said that it had alerted the UK, and officials from the National Cyber Security Centre are understood to have tested several phones but were unable to locate which one was compromised.

Boris Johnson must pay attention to basic cybersecurity rules, says security adviser

Peter Ricketts’ warning comes as UAE accused of using Pegasus spyware to hack into mobile phone at Downing Street

Vihreä mies

Kersantti

Kaverille tuli tekstari, jossa linkki e-aktia. fi - sivustolle. Ei pidä klikkailla.

Neil Madden, the researcher at security firm ForgeRock who discovered the vulnerability, likened it to the blank identity cards that make regular appearances in the sci-fi show Doctor Who. The psychic paper the cards are made of causes the person looking at it to see whatever the protagonist wants them to see.

“It turns out that some recent releases of Java were vulnerable to a similar kind of trick, in the implementation of widely-used ECDSA signatures,” Madden wrote. “If you are running one of the vulnerable versions then an attacker can easily forge some types of SSL certificates and handshakes (allowing interception and modification of communications), signed JWTs, SAML assertions or OIDC id tokens, and even WebAuthn authentication messages. All using the digital equivalent of a blank piece of paper.”

He continued:

“It’s hard to overstate the severity of this bug. If you are using ECDSA signatures for any of these security mechanisms, then an attacker can trivially and completely bypass them if your server is running any Java 15, 16, 17, or 18 version before the April 2022 Critical Patch Update (CPU). For context, almost all WebAuthn/FIDO devices in the real world (including Yubikeys use ECDSA signatures and many OIDC providers use ECDSA-signed JWTs.”

The bug, tracked as CVE-2022-21449, carries a severity rating of 7.5 out of a possible 10, but Madden said based on his assessment, he’d rate the severity at a perfect 10 “due to the wide range of impacts on different functionality in an access management context.” In its grimmest form, the bug could be exploited by someone outside a vulnerable network with no verification at all.

Other security experts also had strong reactions, with one declaring it “the crypto bug of the year.”

Major cryptography blunder in Java enables “psychic paper” forgeries

A failure to sanity check signatures for division-by-zero flaws makes forgeries easy.

In a writeup published Wednesday, security firm Sophos further explained the process:

S1. Select a cryptographically sound random integer K between 1 and N-1 inclusive.

S2. Compute R from K using Elliptic Curve multiplication.

S3. In the unlikely event that R is zero, go back to step 1 and start over.

S4. Compute S from K, R, the hash to be signed, and the private key.

S5. In the unlikely event that S is zero, go back to step 1 and start over.

For the process to work correctly, neither R nor S can ever be a zero. That’s because one side of the equation is R, and the other is multiplied by R and a value from S. If the values are both 0, the verification check translates to 0 = 0 X (other values from the private key and hash), which will be true regardless of the additional values. That means an adversary only needs to submit a blank signature to pass the verification check successfully.

apumekaanikko

Majuri

Anonymous lupaa suojata Suomen kybertilaa ryssän Nato-kiukkuilulta,

itse viesti alkaa n. 38 s. kohdalta

IT Army Ukraine - Anonymous stands strong with Finland

itse viesti alkaa n. 38 s. kohdalta

IT Army Ukraine - Anonymous stands strong with Finland  x Ukraine

x Ukraine

Anonymous lupaa suojata Suomen kybertilaa ryssän Nato-kiukkuilulta,

Kun kerran väittävät hakkeroituneensa komentoverkkoon ym., niin tietäen Venäjän huoltokapasiteetin niin voisi olla ihan kiva tilailla rintamalle kuormittain perseensuristimia ykkösluokan prioriteetilla... kyllä nyt joku huoltojuna ja kuorkkikolonna voi sen verran väistää että tärkeä täydennys saapuu...

Sing Sing

Korpraali

Eilen suoritin MPK/JYU kansalaisen kyberturvallisuuskurssin läpi. Nyt ois kai tarkoitus jatkaa ammatin ja opintojen pohjalta kyberpolulla. Jospa 45,5-vuotiasta vielä tarvittaisiin kybersotaan. Vaikkakin kyber-asia on varsin laaja, ei pelkästään tietotekniikkaa, joskin se on tässä vaiheessa merkittävä.

Erityinen osaamisalueeni on perustason tietoturva yms. asioiden lisäksi trollaus ja häiriköinti. Olen tutkinut ja harrastanut tätä 90-luvun alusta (aluksi BBS:t) asti ja ollut 2016 MPK informaatiovaikuttamiskurssilla luennoitsijana aiheesta trollaus ja taktinen häiriköinti. Pidän omatoimisia "kertausharjoituksia" mm. suoli24-palstan autokeskusteluissa jossa "löylyn heittäminen" on mukavaa koska niihin lankeaa niin moni normo. Automerkit herättävät tunteita. Venäjän toiminnasta olen oppinut paljon ja kehittänyt paljon omiakin keinoja.

Kerran olen joutunut poliisikuulusteluihin trollailun takia, mutta ei tullut syytettä . Kuitenkin näistä on kertynyt mielestäni vankkaa osaamista.

. Kuitenkin näistä on kertynyt mielestäni vankkaa osaamista.

Erityinen osaamisalueeni on perustason tietoturva yms. asioiden lisäksi trollaus ja häiriköinti. Olen tutkinut ja harrastanut tätä 90-luvun alusta (aluksi BBS:t) asti ja ollut 2016 MPK informaatiovaikuttamiskurssilla luennoitsijana aiheesta trollaus ja taktinen häiriköinti. Pidän omatoimisia "kertausharjoituksia" mm. suoli24-palstan autokeskusteluissa jossa "löylyn heittäminen" on mukavaa koska niihin lankeaa niin moni normo. Automerkit herättävät tunteita. Venäjän toiminnasta olen oppinut paljon ja kehittänyt paljon omiakin keinoja.

Kerran olen joutunut poliisikuulusteluihin trollailun takia, mutta ei tullut syytettä

. Kuitenkin näistä on kertynyt mielestäni vankkaa osaamista.

. Kuitenkin näistä on kertynyt mielestäni vankkaa osaamista.

Viimeksi muokattu:

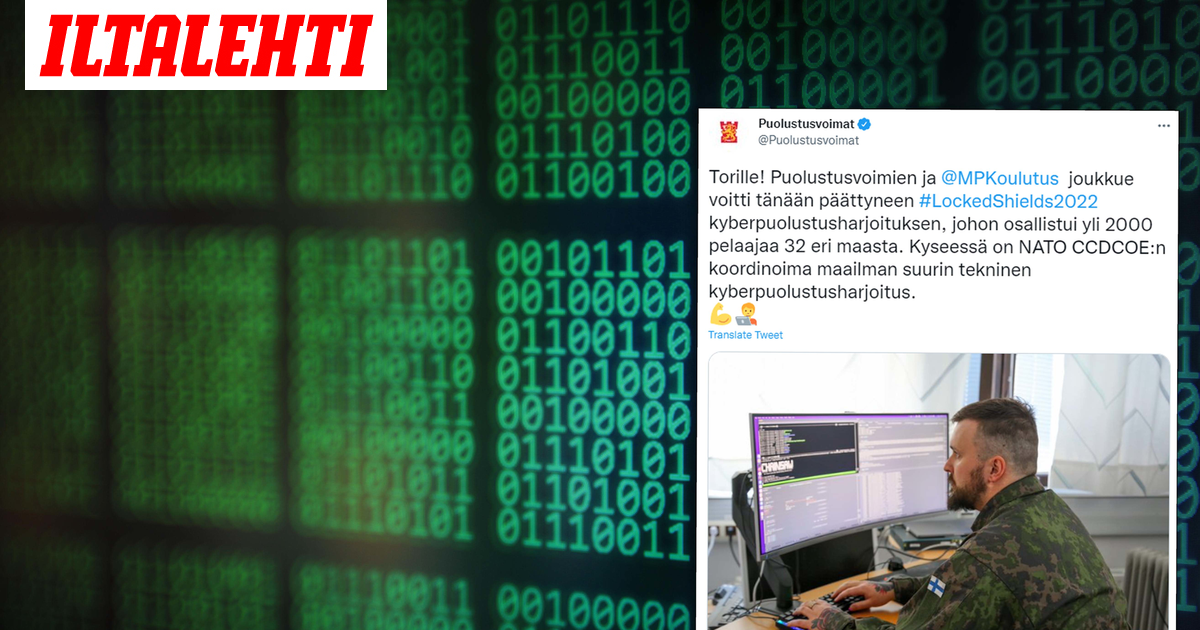

Puolustusvoimien ja Maanpuolustuskoulutuksen (MPK) joukkue voitti maailman suurimman teknisen kyberpuolustusharjoituksen.

Harjoituksen koordinoi sotilasliitto Naton kyberhyökkäyksiin erikoistunut yksikkö.

Kyseessä on Locked Shields- niminen harjoitus, johon osallistui yli 2000 pelaajaa 32 eri maasta. Harjoitus päättyi eilen.

Suomi voitti Naton järjestämän erikoisharjoituksen

Suomi tuli ensimmäiselle sijalle Naton koordinoimassa kyberpuolustusharjoituksessa.

Previously unknown “zero-day” software vulnerabilities are mysterious and intriguing as a concept. But they're even more noteworthy when hackers are spotted actively exploiting the novel software flaws in the wild before anyone else knows about them. As researchers have expanded their focus to detect and study more of this exploitation, they're seeing it more often. Two reports this week from the threat intelligence firm Mandiant and Google's bug hunting team, Project Zero, aim to give insight into the question of exactly how much zero-day exploitation has grown in recent years.

Mandiant and Project Zero each have a different scope for the types of zero-days they track. Project Zero, for example, doesn't currently focus on analyzing flaws in Internet-of-things devices that are exploited in the wild. As a result, the absolute numbers in the two reports aren't directly comparable, but both teams tracked a record high number of exploited zero-days in 2021. Mandiant tracked 80 last year compared to 30 in 2020, and Project Zero tracked 58 in 2021 compared to 25 the year before. The key question for both teams, though, is how to contextualize their findings, given that no one can see the full scale of this clandestine activity.

Hackers are exploiting 0-days more than ever

Mandiant and Google both reported a spike in 0-day bugs in 2021.

“There are definitely more zero-days being used than ever before,” he says. “The overall count last year for 2021 shot up, and there are probably a couple of factors that contributed, including the industry's ability to detect this. But there's also been a proliferation of these capabilities since 2012,” the year that Mandiant's report looks back to. “There's been a significant expansion in volume as well as the variety of groups exploiting zero-days,” he says.

The first bug bounty program by America's Homeland Security has led to the discovery and disclosure of 122 vulnerabilities, 27 of which were deemed critical.

In total, more than 450 security researchers participated in the Hack DHS program and identified weaknesses in "select" external Dept of Homeland Security (DHS) systems. At the end of the hack-a-thon, the department awarded these carefully vetted bug hunters $125,600 total for finding and disclosing the flaws, which is relatively cheap considering, for instance, Google has paid out millions for similar bugs. More cash is set to come from Homeland Security, we note.

"The enthusiastic participation by the security researcher community during the first phase of Hack DHS enabled us to find and remediate critical vulnerabilities before they could be exploited," DHS Chief Information Officer Eric Hysen said in a statement.

DHS did not immediately respond to The Register's questions about the bugs found and fixed through Hack DHS.

The department announced the program in December and modeled it after the Department of Defense's Hack the Pentagon as well as private bug bounty efforts, such as those run by Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and virtually every other major technology company.

Hack DHS followed a pilot bug bounty program that the department trialed in 2019 as part of the SECURE Technology Act. DHS also offered bounties for reports of Log4j vulnerabilities in any public-facing information system assets, which "allowed the department to identify and close vulnerabilities not surfaced through other means," the organization said in a statement.

Homeland Security bug bounty program reveals 122 holes

Thinking of another word for this US govt department's name

Yuga Labs, the multibillion-dollar collective behind the infamous Bored Ape Yacht Club non-fungible tokens, has been targeted by another hacking attack, leading to the theft of millions of dollars worth of the simian NFTs.

BAYC’s series of algorithmically generated cartoon ape profile pictures is one of the best-known collections of NFTs – a digital asset or artwork whose ownership is stored on a blockchain, a decentralised ledger of transactions like those used by cryptocurrencies.

The attacker seized control of the BAYC Instagram account and sent a phishing post that many followers were fooled into clicking on, connecting their crypto wallets to the hacker’s “smart contract” – a mechanism for implementing a crypto transaction. That enabled the attacker to steal the assets held in the wallets, seizing control of four Bored Apes, as well as a host of other NFTs with an estimated total value of $3m.

“Instagram attacks are nothing new but often take an element of social engineering,” said Jake Moore, global cybersecurity adviser at the security firm ESET. “Unfortunately, however, this takeover has had a huge consequence and resulted in a mass robbery of digital assets. Similar to when physical art is stolen, there will be questions over how they would now be able to sell on these assets, but the problems in NFTs still prevail and users must remain extremely cautious of this still very new technology.”

As one of the most prominent NFT collections, with celebrity owners including Eminem, Gwyneth Paltrow and Madonna, BAYC holders are often targeted for attacks, with greater or lesser technical significance.

In early April, for instance, one pseudonymous owner, “s27”, lost a $500,000 ape collection after being tricked into swapping it for, effectively, counterfeits: the scammer created new NFTs that were visually identical to BAYC pictures except they had a green tick over them – mimicking the “verified” icon of the platform used for the trade.

In December, another Ape holder, the New York art dealer Todd Kramer, disclosed his own $2.2m loss with the tweet, “I been hacked. All my apes gone. This just sold please help me.” Kramer, who had fallen prey to a similar phishing scam, managed to recover a portion of his stolen Apes with the help of the NFT trading platform OpenSea – but not before the phrase “all my apes gone” was widely mocked online among those who doubt the substance of the NFT fad.

The BAYC creators said in a statement: “Yuga Labs and Instagram are currently investigating how the hacker was able to gain access to the account. Two-factor authentication was enabled and the security practices surrounding the IG account were tight.”

Hack on Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs leads to $3m simian oblivion

Latest mass theft of digital art assets is carried out by phishing post on Instagram

Sophisticated hackers believed to be tied to the North Korean government are actively targeting journalists with novel malware dubbed Goldbackdoor. Attacks have consisted of multistage infection campaign with the ultimate goal of stealing sensitive information from targets. The campaign is believed to have started in March and is ongoing, researchers have found.

Researchers at Stairwell followed up on an initial report from South Korea’s NK News, which revealed that a North Korean APT known as APT37 had stolen info from the private computer of a former South Korean intelligence official. The threat actor–also known as Ricochet Collima, InkySquid, Reaper or ScarCruft—attempted to impersonate NK News and distributed what appeared to be a novel malware in an attempt to target journalists who were using the official as a source, according to the report.

NK News passed details to Stairwell for further investigation. Researchers from the cybersecurity firm uncovered specific details of the malware, called Goldbackdoor. The malware is likely a successor of the Bluelight malware, according to a report they published late last week.

Nation-state Hackers Target Journalists with Goldbackdoor Malware

A campaign by APT37 used a sophisticated malware to steal information about sources , which appears to be a successor to Bluelight.

“One of these artifacts was a new malware sample we have named Goldbackdoor, based on an embedded development artifact,” they wrote.

Goldbackdoor is a multi-stage malware that separates the first stage tooling and the final payload, which allows the threat actor to halt deployment after initial targets are infected, researchers said.

“Additionally, this design may limit the ability to conduct retrospective analysis once payloads are removed from control infrastructure,” they wrote in the report.

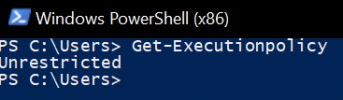

Goldbackdoor is a sophisticated malware that researchers broke down into two stages. In stage one, a victim must download a ZIP file from a compromised site, https[:]//main[.]dailynk[.]us/regex?id=oTks2&file=Kang Min-chol Edits2.zip, which executes a compressed Windows shortcut.

“The domain dailynk[.]us was likely chosen to impersonate NK News (dailynk[.]com),” researchers said, and had been previously used by APT37 in a previous campaign.

Stairwell researchers retrieved the ZIP file for analysis from a DNS history of the site, which had stopped resolving already by the time of their investigation. They identified that the file was created on March 17 and contained a 282.7 MB Windows shortcut file LNK named Kang Min-chol Edits, likely a reference to Kang Min-chol, North Korea’s Minister of Mining Industries.

“The attackers masqueraded this shortcut as a document, using both the icon for Microsoft Word and adding comments similar to a Word document,” researchers wrote.

They also padded the LNK file 0x90, or NOP/No Operation, bytes to artificially increase the size of this file, potentially as a means of preventing upload to detection services or malware repositories they said.

Once executed, the LNK executes a PowerShell script that writes and opens a decoy document before starting the deployment process of Goldbackdoor, researchers said.

After deploying the decoy document, the PowerShell script decodes a second PowerShell script that then will download and execute a shellcode payload XOR—named “Fantasy” stored on Microsoft OneDrive.

That Fantasy payload is the second stage of the malware’s process, and the first of a two-part final process for deploying Goldbackdoor, researchers said.

“Both parts are written in position-independent code (shellcode) containing an embedded payload, and use process injection to deploy Goldbackdoor,” they wrote.

Once executed, the LNK executes a PowerShell script

Tuota, ihan ei selvinnyt kerta lukemisella tuon toiminta. Eli se suoritettava ohjelma käy läpi system32-kansion yrittäen löytää tiedoston johon sillä/käyttäjällä on lukuoikeus, jonka jälkeen suorittaa _sen_ ohjelman niillä oikilla mutta oikeasti suoritetaankin PS-scripti?

Toki jos tuo on asetuksena, niin ei sitten mistään muustakaan kannata huolestua.../s ... se ei ole kylläkään oletuksena...

Tuon jälkeen sitten ladataan se varsinainen takaovi.

On March 1, Russian forces invading Ukraine took out a TV tower in Kyiv after the Kremlin declared its intention to destroy “disinformation” in the neighboring country. That public act of kinetic destruction accompanied a much more hidden but no less damaging action: targeting a prominent Ukrainian broadcaster with malware to render its computers inoperable.

The dual action is one of many examples of the “hybrid war” Russia has waged against Ukraine over the past year, according to a report published Wednesday by Microsoft. Since shortly before the invasion began, the company said, hackers in six groups aligned with the Kremlin have launched no fewer than 237 operations in concert with the physical attacks on the battlefield. Almost 40 of them targeting hundreds of systems used wiper malware, which deletes essential files stored on hard drives so the machines can’t boot.

“As today’s report details, Russia’s use of cyberattacks appears to be strongly correlated and sometimes directly timed with its kinetic military operations targeting services and institutions crucial for civilians,” Tom Burt, Microsoft corporate vice president for customer security, wrote. He said the “relentless and destructive Russian cyberattacks” were particularly concerning because many of them targeted critical infrastructure that could have cascading negative effects on the country.

It’s not clear if the Kremlin is coordinating cyber operations with kinetic attacks or if they’re the result of independent bodies pursuing a common goal of disrupting or degrading Ukraine’s military and government while undermining citizens' trust in those institutions. What’s undeniable is that the two components in this hybrid war have complemented each other.

Examples of Russian cyber actions correlating to political or diplomatic development taken against Ukraine before the invasion began include:

- The deployment of wiper malware dubbed WhisperGate on a “limited number” of Ukrainian government and IT sector networks on January 3 and the defacement and DDoSing of Ukrainian websites a day later. Those actions came as diplomatic talks between Russia and Ukrainian allies broke down.

- DDoS attacks waged on Ukrainian financial institutions on February 15 and February 16. On February 17, the Kremlin said it would be “forced to respond” with military-technical measures if the US didn’t capitulate to Kremlin demands.

- The deployment on February 23 of wiper malware by another Russian state group on hundreds of Ukrainian systems in the government, IT, energy, and financial sectors. Two days earlier, Putin recognized the independence of Ukrainian separatists aligned with Russia.

Russia wages “relentless and destructive” cyberattacks to bolster Ukraine invasion

Cyberattacks complement and are sometimes timed to military actions.

arstechnica.com

arstechnica.com

Vulnerabilities recently discovered by Microsoft make it easy for people with a toehold on many Linux desktop systems to quickly gain root system rights— the latest elevation of privileges flaw to come to light in the open source OS.

As operating systems have been hardened to withstand compromises in recent years, elevation of privilege (EoP) vulnerabilities have become a crucial ingredient for most successful hacks. They can be exploited in concert with other vulnerabilities that on their own are often considered less severe, with the latter giving what’s called local access and the former escalating the root access. From there, adversaries with physical access or limited system rights can deploy backdoors or execute code of their choice.

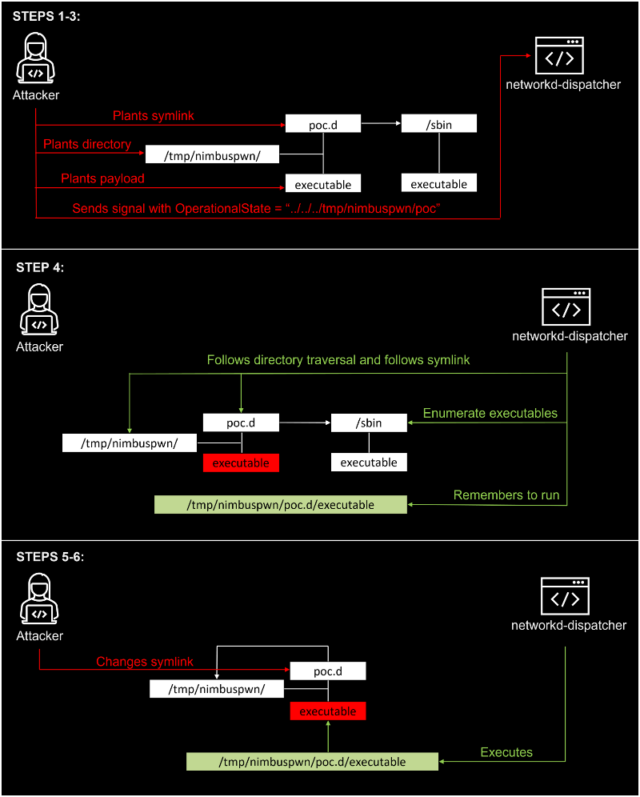

Nimbuspwn, as Microsoft has named the EoP threat, is two vulnerabilities that reside in the networkd-dispatcher, a component in many Linux distributions that dispatch network status changes and can run various scripts to respond to a new status. When a machine boots, networkd-dispatcher runs as root.

Microsoft finds Linux desktop flaw that gives root to untrusted users

Elevation of privilege vulnerabilities can be used to gain persistent root access.

arstechnica.com

arstechnica.com

The proof-of-concept exploit works only when it can use the “org.freedesktop.network1” bus name. The researcher found several environments where this happens, including Linux Mint, in which the systemd-networkd by default doesn’t own the org.freedodesktop.network1 bus name at boot.

The researcher also found several processes that run as the systemd-network user, which is permitted to use the bus name required to run arbitrary code from world-writable locations. The vulnerable processes include several gpgv plugins, which are launched when apt-get installs or upgrades, and the Erlang Port Mapper Daemon, which allows running arbitrary code under some scenarios.

The vulnerability has been patched in the networkd-dispatcher, although it wasn’t immediately clear when or in what version, and attempts to reach the developer weren’t immediately successful. People using vulnerable versions of Linux should patch their systems as soon as possible.

China appears to be entering a raging cyber-espionage battle that's grown in line with Russia's unprovoked attack on Ukraine, deploying advanced malware on the computer systems of Russian officials.

Bronze President, a China-linked threat group that typically targeted government entities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Southeast Asia to collect information for the Chinese government, is shifting its focus, Secureworks' Counter Threat Unit wrote in today's report.

"Changes to the political landscape can impact the collection requirements" of state-sponsored threat groups, the researchers wrote. "The war in Ukraine has prompted many countries to deploy their cyber capabilities to gain insight about global events, political machinations, and motivations. This desire for situational awareness often extends to collecting intelligence from allies and 'friends.'"

In the case of Bronze President – an advanced persistent threat (APT) group also known as Mustang Panda, RedDelta, and TA416 – "targeting Russian-speaking users and European entities suggests that the threat actors have received updated tasking that reflects the changing intelligence collection requirements of the PRC [People's Republic of China]."

China has tried to play a neutral role since Russia began its invasion of Ukraine on February 24, with government officials saying they want to see a peaceful resolution. That said, China has not condemned the attack and has spoken out against the mounting sanctions from the United States and Western allies on Russia and its oligarchs.

The Middle Kingdom has long been a key Russian trading partner while also a rival for authority in that region. Now China is turning some of its extensive cyber capabilities on its neighbor.

CTU threat hunters in March analyzed a malicious executable file that appeared to be a Russian-language document with a file name of "Blagoveshchensk Border Detachment.exe" written in Russian. According to the researchers, Blagoveshchensk is a Russian city near the border with China that houses the 56th Blagoveshchenskiy Red Banner Border Guard Detachment.

"This connection suggests that the filename was chosen to target officials or military personnel familiar with the region," they wrote.

Default settings on Windows systems didn't display the .exe extension of the decoy file, which instead uses a PDF icon to appear credible. The document is written in English and appears to be legitimate, outlining the pressures on Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland – which border Russian ally Belarus – created by mass migration of Ukrainians fleeing the war and seeking asylum.

The document also addresses sanctions the European Union placed on Belarus in early March for its role in supporting Russia's aggression. The Secureworks researchers said they were unsure why a file that carries a Russian name comes with a document written in English.

China launches cyber-espionage malware campaign

State-sponsored Bronze President group launches cyber-espionage malware campaign against notional ally

Hyvä palkkio olisi luvassa

www.forbes.com

www.forbes.com

Russian Military Hackers—$10 Million Reward Offered By U.S. Government

$10 million reward offered for location of six Russian military hackers

www.forbes.com

www.forbes.com