https://warisboring.com/for-japan-air-to-air-fighters-trump-other-jets-7d4f6725c28e#.pnwhfe8f2In late June, the Japanese ministry of defense made its initial request for information on next-generation jet fighters from manufacturers, kickstarting the long process of replacing the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force’s Mitsubishi F-2 multirole fighters with a new “F-3.”

But as Tokyo looks to counter an increasingly sophisticated Chinese air and naval threat, none of the existing aircraft that are currently available for purchase seems likely to fit Japan’s needs.

What Japan really wants is the American F-22. Legally barred from buying that plane, Japan’s likely next-best option is to design and manufacture a new stealth fighter entirely on its own. It’s a weighty decision with huge implications.

...

To understand why Tokyo wants to improve its counter-air capabilities, you need only look at how quickly China has become a major threat to the Ryukyu island chain.

During the Cold War, Japan’s forces faced north to defend against the Soviet Union. But Japan was slow to adjust to the post-Cold War environment, keeping those northern forces in place even as tensions decreased between Moscow and Tokyo.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the Japanese Self-Defense Forces struggled to justify their existence to the public — taking on peacekeeping missions, international disaster and humanitarian relief operations and even engaging in anti-terrorism and nation-building operations in the Middle East

But in 2010, after years of growing concern among Japanese conservatives, the Ministry of Defense found its new threat. That year’s National Defense Program Guidelines highlighted China’s blue-water navy ambitions, its interest in anti-access and area-denial weaponry and its fresh interest in the disputed Senkaku islands.

It’s easy to understand Japan’s concerns. .

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2...litary-drills-ahead-of-key-territorial-rulingChina has kicked off a week of military drills in the South China Sea ahead of a hotly anticipated and potentially destabilising court ruling on its territorial claims in the region.

CCTV, the country’s state broadcaster, said the manoeuvres were due to start at about 8am Beijing time on Tuesday.

At least two guided missile destroyers, the Shenyang and Ningbo, and one missile frigate, the Chaozhou, were reported to be among the vessels being deployed to the region, where China has overlapping territorial claims with Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

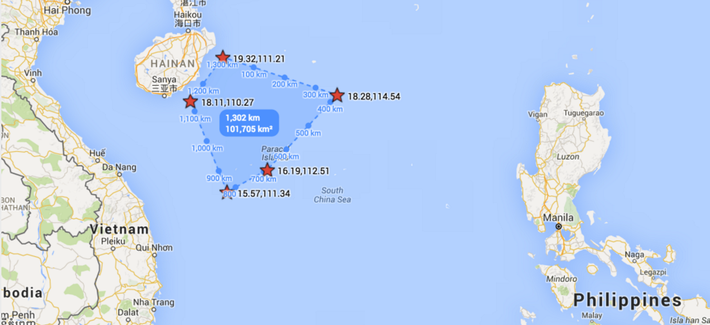

The exercises, inside a 100,000 square kilometre zone around the disputed Paracel Islands, come ahead of a ruling next week by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague over a long-standing territorial dispute between the Philippines and China.

http://www.defenseone.com/threats/2...l-zone-disputed-waters-during-wargame/129607/The PLA Navy has designated a trapezoid of some 38,000 square miles, located in the South China Sea between Vietnam and the Philippines, for a series of naval exercises that began on America’s Independence Day and will wrap up just before an international body is expected to rule on territorial claims. Other nations’ vessels are not to intrude, Beijing said in a press release over the weekend.

Viimeksi muokattu:

Japani on kiinnostautuneet tekemään kauppoja iippojen kanssa, varsinkin lennokkimarkkinoilla.

http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com...der-partnership-with-israeli-industry-034188/Defense officials from Japan are considering a partnership with Israeli industry to research unmanned surveillance aircraft and fighters. The proposal would see Japan’s Acquisition, Technology & Logistics Agency work with the SIBAT defense cooperation department of Israel’s Defense Ministry on how Japanese sensor technologies can be integrated with Israeli airframes. Until 2014, Japan’s arms export principles banned the country from exporting arms to a state that may potentially become a conflict country. This prevented cooperation with Israel due to its conflict with Palestine

http://www.spacewar.com/reports/Chi...flict_in_South_China_Sea_state_media_999.htmlBeijing must prepare for "military confrontation" in the South China Sea, state-run media said Tuesday, as it began naval drills in the area ahead of an international tribunal ruling over the maritime dispute.

China asserts sovereignty over almost all of the resource-rich strategic waterway despite rival claims from Southeast Asian neighbours -- raising tensions with the United States, which has key defence treaties with many allies in the region.

On Tuesday, China began a week of naval exercises in waters around the Paracel Islands.

They come a week before a United Nations-backed tribunal in The Hague rules on a case brought by the Philippines challenging China's position.

Beijing has boycotted the hearings and is engaged in a major diplomatic and publicity drive to try to delegitimise the process.

In an editorial, the Global Times -- a newspaper owned by the People's Daily group that often takes a nationalistic tone -- said China should accelerate the build-up of its defence capabilities and "must be prepared for any military confrontation".

"Even though China cannot keep up with the US militarily in the short-term, it should be able to let the US pay a cost it cannot stand if it intervenes in the South China Sea dispute by force," it added.

In recent years Beijing has rapidly built up reefs and outcrops into artificial islands with facilities capable of military use.

Manila lodged its suit against Beijing in early 2013, saying that after 17 years of negotiations it had exhausted all political and diplomatic avenues to settle the dispute.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) will issue its ruling on July 12, though China has consistently rejected the tribunal's right to hear the case and has taken no part in the proceedings.

The arbitration case had been orchestrated by the Philippines and the US to portray China as "an outcast from a rules-based international community", said an editorial in the China Daily.

The newspaper, which is published by the government, added: "It is naive to expect China to swallow the bitter pill of humiliation".

http://www.spacewar.com/reports/Philippines_Duterte_to_China_Lets_talk_999.htmlPhilippine President Rodrigo Duterte on Tuesday offered China conciliatory talks on a long-awaited international tribunal ruling over Beijing's maritime claims, a week before the verdict.

Duterte, who was sworn into office last week, said he was optimistic that the UN-backed tribunal in The Hague would rule in favour of the Philippines.

"If it's favourable to us, let's talk," Duterte said in a speech before the Philippine Air Force at the former US military base of Clark, about an hour's drive from the capital Manila.

http://www.spacewar.com/reports/Chinese_Japanese_warplanes_in_close_encounter_999.htmlBeijing and Tokyo were at loggerheads Tuesday over accusations Japanese warplanes locked their fire control radar onto Chinese aircraft, as state-run Chinese media said the country needed to be ready for "military confrontation" elsewhere.

Beijing has long been embroiled in fierce territorial disputes with Tokyo over Japanese-controlled islands in the East China Sea, and with a host of littoral states over the South China Sea, which it claims almost in its entirety.

Chinese vessels and planes regularly enter waters and airspace near the East China Sea islands, called Senkaku in Japan and Diaoyu in China.

China's defence ministry late Monday accused Japanese fighter jets of using their fire control radar to lock onto two Chinese aircraft on "routine patrol" in the Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) it declared unilaterally in 2013.

The aggressive move generally means an attacker is ready to fire weapons at a target.

Japan's deputy chief cabinet secretary Koichi Hagiuda denied the accusation Tuesday, telling reporters that Tokyo's Self-Defence Forces had scrambled F15 jets to monitor Chinese aircraft.

"There are no facts showing that we took provocative action against Chinese military planes," he said.

In 2013, Tokyo demanded Beijing apologise when it said a Chinese frigate had locked its fire-control radar onto a Japanese destroyer in international waters.

The row over the islands has seen relations between the world's second- and third-largest economies plunge in recent years, before recovering slightly, although they remain poor.

Pystyykö kiina ottamaan kerta rysäyksellä kaikki sen haluamat saaret haltuun ja pitämään niistä kiinni?

Jos Trump valitaan, niin jenkit keskittyy entistä enemmän pitämään pesäeroa Kiinaan. Japani ja jopa Australia sekä Uusi-Seelanti punnitsevat puolustustaan Kiinan uhkaan.http://www.spacewar.com/reports/Chi...flict_in_South_China_Sea_state_media_999.html

http://www.spacewar.com/reports/Philippines_Duterte_to_China_Lets_talk_999.html

http://www.spacewar.com/reports/Chinese_Japanese_warplanes_in_close_encounter_999.html

Pystyykö kiina ottamaan kerta rysäyksellä kaikki sen haluamat saaret haltuun ja pitämään niistä kiinni?

Jos Kiina onnistuu Venäjän kanssa liittoutumaan, niin jonkinnäköinen yllätysvaltaus saattaisi ehkä onnistuakin.

Kiina tuskin lähtee sotajalalle, koska USAn markkinat ovat jatkossakin Kiinalle elinehto. Jonkinlainen kriisi saattaa syttyä kuitenkin ihan vahingossakin. Kiinalainen hävittäjä pudottaa vahingossa amerikkalaisen tiedustelukoneen etc..

Oho, BBC ennustaa sukellusvenesotaa

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-36574590A tribunal is about to rule on China's territorial claims in the disputed South China Sea. But Beijing's desire for control is about much more than rocks above the water, argues analyst Alexander Neill. It is also central to China's plans for a submarine nuclear force able to break out into the Pacific Ocean.

Historically, China's national infrastructure projects have tended to be of grandiose scale - the Great Wall of China and the Three Gorges Dam are ancient and modern examples. China has now proved such a capability at sea with the imminent opening of a string of advanced military bases across the South China Sea, where just two years ago little more than rocky outcrops, sandbars and reefs dotted the region.

International attention has focused on why Beijing's constructed these artificial islands so speedily. There is speculation that with the imminent announcement of the ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague on the Philippines' territorial dispute with China, Beijing fast-tracked the project to create a fait accompli or a "great wall of sand".

For China, national sovereignty and the credibility of the Communist Party is at stake. But so too is its new sea-based nuclear deterrent.

Woody Island.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2...court-ruling-on-its-claims-in-south-china-seaBeijing has unleashed a final salvo of defiance, propaganda and bravado with hours to go until a landmark court ruling that could deal a major blow to its territorial claims in the South China Sea.

More than three years after the Philippines asked the permanent court of arbitration in The Hague to dismiss many of China’s sweeping claims in the resource-rich region, the court is set to announce its decision at around 11am Tuesday CEST (10am BST).

China has refused to recognise the five-judge court’s authority and on Tuesday morning the country’s Communist party-controlled press lashed out at what it claimed was a United States-sponsored conspiracy to stifle its rise.

“China in the past was weak … but now it has multiple means at its disposal,” warned the Global Times, a nationalist Communist party tabloid, in an editorial, adding: “Provocateurs are doomed to fail.”

The China Daily, Beijing’s English-language mouthpiece, dismissed the court case as a “farce directed by Washington”.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-36767252

Viimeksi muokattu:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-36771749International tribunal rules against Chinese claims to rights in South China Sea; China calls ruling "ill-founded"

The Permanent Court of Arbitration said there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or resources.

China described the ruling as "ill-founded".

China claims almost all of the South China Sea, including reefs and islands also claimed by others.

The tribunal in The Hague said China had violated the Philippines' sovereign rights. It also said China had caused "severe harm to the coral reef environment" by building artificial islands-

The ruling came from an arbitration tribunal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which both countries have signed.

The ruling is binding but the tribunal, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, has no powers of enforcement.

The US sent an aircraft carrier and fighter jets to the region ahead of the ruling, prompting an angry editorial in the Global Times, a strongly nationalist state-run newspaper, calling for the US to prepare for "military confrontation".

Meanwhile, the Chinese Navy has been carrying out exercises near the disputed Paracel islands.

Miten se nyt menikään, sota on politiikan jatkumo, ei syy. Saa nähdä miten tässä edetään, kun kiinalla tuntuu olevan kovat piipussa valmiiksi. Samalla tuntuu, että he tiesivät tämän tapahtuvan ja ovat siten varautuneet pitämään kiinni alueen saarista Haagin päätöstä vastaan.

Viimeksi muokattu:

http://en.people.cn/n3/2016/0712/c90000-9085054.htmlStatement of the Government of the People' s Republic of China on China' s Territorial Sovereignty and Maritime Rights and Interests in the South China Sea

To reaffirm China' s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea, enhance cooperation in the South China Sea with other countries,and uphold peace and stability in the South China Sea, the Government of the People' s Republic of China hereby states as follows:

I. China' s Nanhai Zhudao (the South China Sea Islands) consist of Dongsha Qundao (the Dongsha Islands), Xisha Qundao (the Xisha Islands), Zhongsha Qundao (the Zhongsha Islands) and Nansha Qundao (the Nansha Islands). The activities of the Chinese people in the South China Sea date back to over 2,000 years ago. China is the first to have discovered, named, and explored and exploited Nanhai Zhudao and relevant waters, and the first to have exercised sovereignty and jurisdiction over them continuously, peacefully and effectively, thus establishing territorial sovereignty and relevant rights and interests in the South China Sea.

Following the end of the Second World War, China recovered and resumed the exercise of sovereignty over Nanhai Zhudao which had been illegally occupied by Japan during its war of aggression against China. To strengthen the administration over Nanhai Zhudao, the Chinese government in 1947 reviewed and updated the geographical names of Nanhai Zhudao, compiled Nan Hai Zhu Dao Di Li Zhi Lue (A Brief Account of the Geography of the South China Sea Islands), and drew Nan Hai Zhu Dao Wei Zhi Tu (Location Map of the South China Sea Islands) on which the dotted line is marked. This map was officially published and made known to the world by the Chinese government in February 1948.

II. Since its founding on 1 October 1949, the People' s Republic of China has been firm in upholding China' s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea. A series of legal instruments, such as the 1958 Declaration of the Government of the People' s Republic of China on China' s Territorial Sea, the 1992 Law of the People' s Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, the 1998 Law of the People' s Republic of China on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf and the 1996 Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People' s Congress of the People' s Republic of China on the Ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, have further reaffirmed China' s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea.

III. Based on the practice of the Chinese People and the Chinese government in the long course of history and the position consistently upheld by successive Chinese governments, and in accordance with national law and international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, China has territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea, including, inter alia:

i. China has sovereignty over Nanhai Zhudao, consisting of Dongsha Qundao, Xisha Qundao, Zhongsha Qundao and Nansha Qundao;

ii. China has internal waters, territorial sea and contiguous zone, based on Nanhai Zhudao;

iii. China has exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, based on Nanhai Zhudao;

iv. China has historic rights in the South China Sea.

The above positions are consistent with relevant international law and practice.

IV. China is always firmly opposed to the invasion and illegal occupation by certain states of some islands and reefs of China' s Nansha Qundao, and activities infringing upon China' s rights and interests in relevant maritime areas under China' s jurisdiction. China stands ready to continue to resolve the relevant disputes peacefully through negotiation and consultation with the states directly concerned on the basis of respecting historical facts and in accordance with international law. Pending final settlement, China is also ready to make every effort with the states directly concerned to enter into provisional arrangements of a practical nature, including joint development in relevant maritime areas, in order to achieve win-win results and jointly maintain peace and stability in the South China Sea.

V. China respects and upholds the freedom of navigation and overflight enjoyed by all states under international law in the South China Sea, and stays ready to work with other coastal states and the international community to ensure the safety of and the unimpeded access to the international shipping lanes in the South China Sea.

http://www.ft.com/fastft/2016/07/12/un-tribunal-rules-for-philippines-in-south-china-sea-dispute/A UN tribunal has ruled unanimously in favour of the Philippines in its case against China’s extensive claims in the South China Sea.

The Philippines first brought the case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea at The Hague in 2013, raising 15 instances in which it held China’s claims and activity in the South China Sea had violated international law, writes Hudson Lockett. In 2015 the tribunal decided it had jurisdiction on seven of those, though it said it was still considering the other eight.

The tribunal’s decision applies not to sovereignty claims, but the maritime rights attached to such claims. Among the issues raised by the Philippines was the validity of China’s “Nine-dash line” asserting sovereignty over as much as 90 per cent of the region’s waters.

[The] Tribunal concluded that, to the extent China had historic rights to resources in the waters of the South China Sea, such rights were extinguished to the extent they were incompatible with the exclusive economic zones provided for in the Convention. The Tribunal also noted that, although Chinese navigators and fishermen, as well as those of other States, had historically made use of the islands in the South China Sea, there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or their resources. The Tribunal concluded that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within the ‘nine-dash line’.

Kova juttu tuo yk:n päätös. Sen vuoksi kuka Filippiineillä on päässyt valtaan.

Ukko on ihan seko mielestäni. Nationalisti ja retoriikka on kovaa. Huumeiden käyttäjät hirteen.

Tästä kirjoitti busines insider artikkelinkin,mutta en tähän hätään löydä.

Kunhan ei nyt innostu.

Ukko on ihan seko mielestäni. Nationalisti ja retoriikka on kovaa. Huumeiden käyttäjät hirteen.

Tästä kirjoitti busines insider artikkelinkin,mutta en tähän hätään löydä.

Kunhan ei nyt innostu.

Bushmaster

Greatest Leader

Rähinä lähestyy uhkaavasti tyynenmeren suunnalla...

Bushmaster

Greatest Leader

USA:lla on selkeästi suuri rooli tyynenmerenalueen puolustuksessa ja omien kumppaniensa tukemisessa joten USA on ensilinjassa ottamassa osaa tyynenmeren hulabaloohon..mutta Obama voi olla eri mieltä ...?

Kiina jo varoittaa konflikteista ja yhteenotoista Etelä-Kiinan merellä...kummalista kun rauhaa rakastava Kiina rähinästä varoittaa...?

Kiina jo varoittaa konflikteista ja yhteenotoista Etelä-Kiinan merellä...kummalista kun rauhaa rakastava Kiina rähinästä varoittaa...?

Kiina varoittaa konflikteista kiistellyllä merialueella

Tänään klo 08:38

http://m.iltalehti.fi/ulkomaat/2016071321899879_ul.shtml

Kiina varoittaa konflikteista ja yhteenotoista Etelä-Kiinan merellä. Kiina hävisi aluetta koskevan oikeusriidan Filippiineille YK:n pysyvässä tuomioistuimessa eilen.

Kiinan reaktiot tuomioon olivat jo aikaisemmin vihaisia ja torjuvia. Maan ulkoministeriö kuvaili päätöstä muun muassa mitättömäksi. Kiinan Yhdysvaltain-suurlähettilään Cui Tiankain mukaan päätös heikentää mahdollisuuksia ratkaista erimielisyydet Etelä-Kiinan merellä.

Viimeksi muokattu:

Aika ankaria lausuntoja kiinan valtaa pitäviltä.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-36781138

Huvittaa hieman että he laittoivat "lentokiellon" koko alueen päälle. On melkein kuin libyassa taikka irakissa, sodan alussa.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2...national-court-after-south-china-sea-slapdownA front page commentary in the Communist party’s official mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, continued the offensive, dismissing the tribunal as “a lackey of some outside forces” that would be remembered “as a laughing stock in human history”.

“We do not claim an inch of land that does not belong to us, but we won’t give up any patch that is ours,” the newspaper said, adding: “China, of course, will not accept such downright political provocations.”

The China Daily, Beijing’s English-language mouthpiece, claimed the “outrageously one-sided ruling” meant military confrontation in the region had become more likely.

“With military activity reaching unprecedented levels in the South China Sea, there is no guarantee that an escalating war of words will not transform into something more,” it said.

The Global Times, a nationalist tabloid that is controlled by the People’s Daily and is known for its inflammatory rhetoric, was even more direct.

Further political or military pressure from the US – which Beijing has accused of masterminding the case against its claims in the South China Sea – would lead the Chinese people to “firmly support our government to launch a tit-for-tat counterpunch”, it warned.

Liu Zhenmin, China’s vice-foreign minister, said Beijing reserved the right to declare an air defence identification zone over the South China Sea.

“What we have to make clear first is that China has the right to ... But whether we need one in the South China Sea depends on the level of threats we face,” he said, adding that China hoped to return to bilateral talks with Manila.

“We hope that other countries don’t use this opportunity to threaten China, and hope that other countries can work hard with China, meet us halfway, and maintain the South China Sea’s peace and stability, and not turn the South China Sea in a source of war,” Liu said.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-36781138

Huvittaa hieman että he laittoivat "lentokiellon" koko alueen päälle. On melkein kuin libyassa taikka irakissa, sodan alussa.

kausaliteetti

Luutnantti

KV-yhteisön tulee eristää Kiina samoin kuin Venäjä kaikesta yhteistyöstä ja tuoda Putinin lisäksi myös Xi Hagiin. Oikeastaan olisi parempi eristää varmuuden vuoksi koko Aasia, eihän se ole paljonkaan kuuta isompi maapläntti.

Raja railona aukeaa. Edessä Aasia, Itä. Takana Länttä ja Eurooppaa;varjelen, vartija, sitä.

Raja railona aukeaa. Edessä Aasia, Itä. Takana Länttä ja Eurooppaa;varjelen, vartija, sitä.

http://qz.com/730669/chinas-citizen...cause-theyve-always-been-taught-it-is-theirs/Chinese citizens have reacted swiftly and angrily to a ruling this week that China’s claim to most of the South China Sea are illegal.

Patriotic netizens have called for war against the Philippines, a boycott of the country’s products, and created a somewhat racist cartoon to mock Filipinos. They’re jumping the Great Firewall to spit vitriolic, expletive-laden insults on Twitter, and over 20,000 Chinese citizens have signed an open letter to protest against the court ruling.

Many can’t believe the Philippines brought a complaint to an international tribunal to begin with.

“Why were there any disputes?,” Lin Hongguang, a 23-year-old university student now based in Australia, wondered to Quartz. “You don’t have to be taught that the South China Sea belongs to China—just like no one would ask whether northeastern region belongs to China.”

Mitä tähän pitäisi sanoa? Luulo ei ole tiedon värtti.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opin...987c44-4918-11e6-acbc-4d4870a079da_story.htmlCHINA’S COMMUNIST regime is reacting with rhetorical frenzy to a ruling by an international tribunal rejecting its expansive territorial claims in the South China Sea. President Xi Jinping, who has aggressively pushed what has now been formally deemed as illegal construction of bases on contested islets, issued a statement saying that China “will never accept any claim or action based on these awards.” He’s right that the judgment, in a case filed by the Philippines, is unenforceable. But it is a major blow to Mr. Xi’s attempt to establish Chinese hegemony in the region and presents him with a fateful choice: embark on a dangerous escalation, or slowly and quietly back down.

Beijing’s insistence that the court decision is “invalid and has no binding force” only goes so far. The Philippines sued under the Law of the Sea treaty, which China has ratified. That means the decision is legally binding whether Mr. Xi recognizes it or not. Nations far beyond Asia will watch to see if the rising superpower violates a treaty it agreed to be bound by. If it does, the damage to China’s international standing and influence could prove considerably greater than whatever it might gain from fortifying a few coral reefs.

Though the unanimous court judgment was more sweeping than some experts expected, it wasn’t particularly surprising. China has been claiming up to 90 percent of the South China Sea, an area larger than the Gulf of Mexico, based on a vague 1940s map with a “nine-dash line” sketched across it. But the treaty it ratified voided such historical claims and awarded sovereignty over waters based on their distance from coastlines. Scarborough Shoal, the fishing ground that China seized from the Philippines three years ago, is about 500 miles from the Chinese mainland; the tribunal found that Beijing had engaged in multiple unlawful actions in Philippine waters.

Having decisively won its case, the Philippines’ new government is reacting prudently. Foreign Secretary Perfecto Yasay Jr. held out the possibility of negotiations with the Xi regime and said the two governments had agreed not to take “provocative action” in the meantime. The Obama administration, which has beefed up its military alliance with the Philippines in an attempt to deter further Chinese aggression, also responded temperately. That’s fine for now: Mr. Xi, who is due to host a summit of the Group of 20 nations in September, must be given a chance to change course without losing face.

The United States nevertheless must be prepared for the possibility that Mr. Xi will double down on his adventurism, perhaps hoping to take advantage of a president in his last months of office who has responded weakly to red-line crossings in other parts of the world. For some time experts have been concerned China would attempt to militarize Scarborough Shoal, placing planes or missiles 150 miles from Subic Bay in the Philippines; it has also threatened to declare an air defense zone over the South China Sea. Any such action must be contested by the United States. The alternative would be to sanction Mr. Xi’s use of raw power to advance his nationalist aims — and open the way to serious conflict in East Asia.

Bushmaster

Greatest Leader

EU ja eurooppa on riisunut itsensä aseista unelmoidessaan ikuisesta rauhasta ja yrittää nyt kasata rippeistä jotain vastusta Venäjälle mutta Tyynellämerellä on valmistauduttu puolin ja toisin yhteenottoon jo pitkään. USA eikä muut maat joita Kiina painostaa, tule Kiinalle periksi antamaan, joten on vain ajan kysymys milloin leimahtaa...ellei siiten Kiina peräänny, mikä vaikuttaa myös epätodennäköiseltä vaihtoehdolta eli kysymys onkin siitä milloin yhteenotto tapahtuu...?

Kiinalla on ihan samankaltainen retoriikka kuin Venäjällä Gerogian ja Ukrainan sekä Krimin valtauksen kanssa.

Kun on joku tarpeeksi härski niin sellaista ei puheilla eikä neuvotteluilla pysäytetä...

Kiinalla on ihan samankaltainen retoriikka kuin Venäjällä Gerogian ja Ukrainan sekä Krimin valtauksen kanssa.

Kun on joku tarpeeksi härski niin sellaista ei puheilla eikä neuvotteluilla pysäytetä...