KRP: Airiston helmi -jupakka siirtyy syyteharkintaan

Poliisi epäilee rikoksista yhteensä 12 henkilöä.

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

The unfinished war against Ukraine is already changing Europe’s security landscape. The centre of the earthquake is Helsinki. A year ago, only a quarter of Finns wanted to join the Nato alliance; now three fifths do. A government report on the “changed security environment” is by Finnish standards blisteringly phrased: “Russia jeopardises the security and stability of the whole of Europe,” it states. A formal decision is expected by midsummer.

Not that Finland has ever neglected defence. Its insights into its unpredictable neighbour’s thinking, based on intensive contacts and a highly eLective intelligence service, are renowned. In 2012, when most western countries were still in a strategic doze, Finland was the first European country to acquire the formidable AGM-158 JASSM, a stealthy American-made air-to-surface missile that can be fired from far away and strike deep inside Russia. In February it ordered 64 American F-35s, the world’s most advanced warplane, in a £7.2 billion deal.

Finland’s air force conducts cross-border exercises on a near-weekly basis with Norway and non-Nato Sweden. As well as a defence agreement with the United States, it is part of the British-led Joint Expeditionary Force, a grouping of ten north European countries with advanced, mobile military forces and a like- minded approach to Russia.

Finland also practises the kind of physical and psychological resilience that the rest of Nato urgently needs to learn. It maintains big stockpiles of fuel, food and medicine. Universal conscription for men, followed by regular training, underpins the biggest reserve forces in Europe. No other country can mobilise so many people so rapidly. Prestigious three-week courses for senior decision-makers build cohesion and capability in the face of crises: from natural disasters to national- security emergencies. The stellar education system teaches children to spot disinformation almost as soon as they learn to read. A research centre in Helsinki, backed by 31 EU and Nato members, has since 2017 examined “hybrid threats”: Moscow’s cocktail of financial, propaganda, legal, cyber and other mischief.

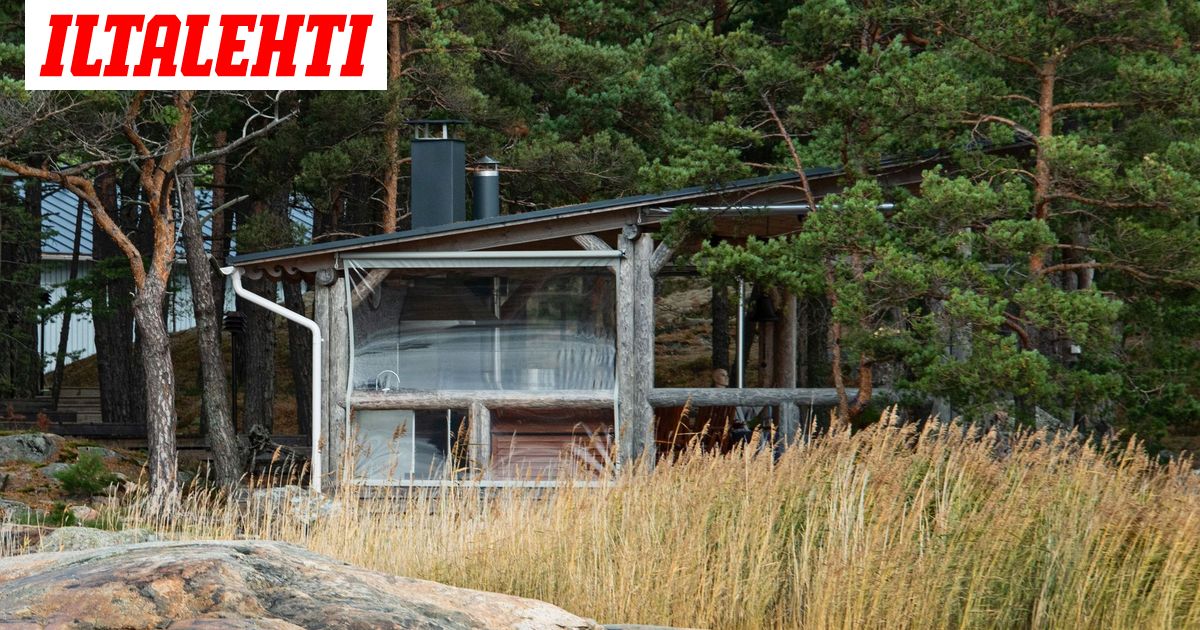

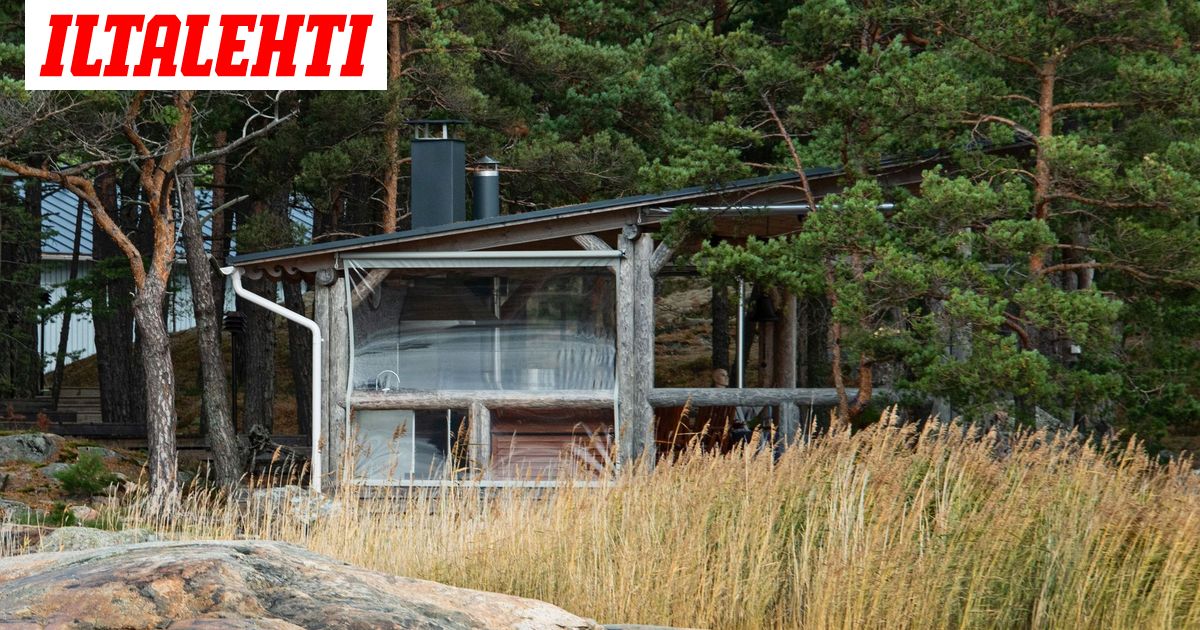

The prime example of Finland’s own approach to this came in September 2018. Sheltered by a no-fly zone, more than 400 o`cials, including special forces, coastguards, military police, intelligence o`cers, tax inspectors and others took part in 17 raids centring on Airiston Helmi, a Russian-run complex of buildings in the country’s southwestern archipelago. The biggest security operation in the country’s peacetime history found encrypted satellite communications, large quantities of cash, plus bunkers, underwater installations and a much-used helicopter pad.

Was this Bond-villain’s lair, close to critical transport and communications infrastructure, a gangland hangout? Or a military-intelligence base? Or both? Nobody will say, pending the outcome of a police investigation which is continuing, seemingly indefinitely. A public fuss would have served no purpose. The private message to Moscow was clear and eLective. A worrying trend of Russian real-estate purchases near sensitive sites stopped immediately.

This discreet, watchful approach stems from bitter historical experience. Finland escaped from Russian rule only 105 years ago, prompting a traumatic civil war between pro-Bolshevik “reds” and nationalist “whites”. In 1939, Stalin launched an unprovoked attack. For 105 days of the Winter War the outnumbered but gutsy Finns inflicted colossal losses on the ill-led, undertrained Soviets; an echo of Ukraine’s struggle now. To this day, Finns mourn the territory they had to cede.

For Nato’s 30 existing members, Finland’s advanced, well-funded armed forces are ideal. Interoperability is already assured. Intelligence-sharing will be smooth. And a vital piece in the security jigsaw falls into place. Assuming (plausibly) that the vacillating Swedes follow the lead from Helsinki, the Baltic Sea will become, in eLect, a Nato lake, sharply constraining Russia’s ability to use its navy and air force against Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

The Kremlin is frothing. Dmitry Medvedev, a Putin stooge now serving as deputy chairman of the national security council, has threatened to deploy nuclear and hypersonic weapons to the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad. As the president of next-door Lithuania, Gitanas Nauseda, noted, Russia is widely assumed to keep nuclear warheads there anyway. But it underlines the troubling impression that the Kremlin sees nuclear threats as its all-purpose response to setbacks.

Russia’s best chance of making trouble will be in the period before Finland’s formal Nato accession, particularly if Sweden is out of step, or if other alliance members (perhaps stroppy Hungary) kick up obstacles. Expect intensive diplomatic spadework on these issues in the coming weeks. The strategically located Aland islands could be tricky, too. Other islands in the Baltic Sea now have garrisons to forestall any Russian stunts. But the Aland islands are demilitarised under a League of Nations treaty signed in 1921. Russia, which keeps a spy nest (under cover of a consulate) in the islands’ capital, Mariehamn, may object to any change.

But any such attempts to frustrate Finland’s move to Nato will merely underline its necessity. Greeted by well-wishers at its rebirth in 1991, Russia is now encircled by countries that at best mistrust and at worst loathe it. For that, Russia’s leaders have only themselves to blame.

Airiston Helmen entinen omistaja Pavel Melnikov joutuu syytteeseen yhtiössä epäillyistä talousrikoksista. Syyttäjä nosti torstaina syytteet Melnikovia ja seitsemää muuta henkilöä vastaan.

Syyttäjä aikoo vaatia yhteisörangaistusta myös Airiston Helmi Oy:lle. Mittavat veronkiertoepäilyt liittyvät yhtiöön, joka omisti useita Turun saaristossa sijaitsevat miljoonien eurojen arvoiset kiinteistöt.