In the popular conception of a technological breakthrough, a flash of genius is followed quickly by commercial or industrial success, public acclaim, and substantial wealth for a small group of inventors and backers. In the real world, it almost never works out that way.

Advances that seem to appear suddenly are often backed by decades of development. Consider

steam engines. Starting in the second quarter of the 19th century they began powering trains, and they soon revolutionized the transportation of people and goods. But steam engines themselves had been invented at the beginning of the

18th century. For 125 years they had been used to

pump water out of mines and then to power the mills of the Industrial Revolution.

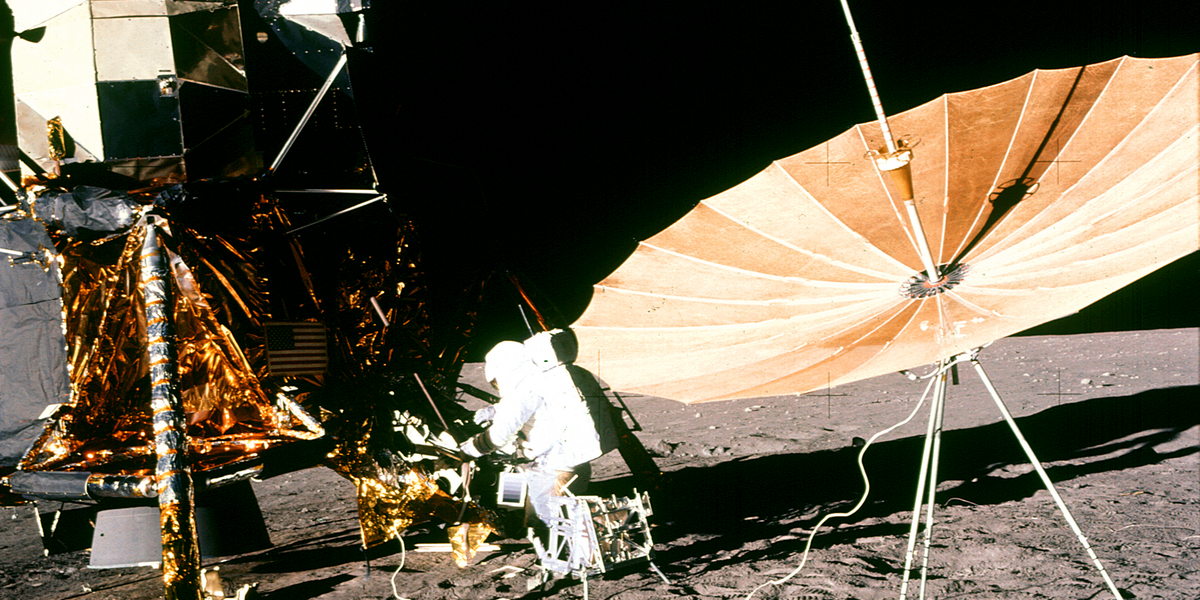

Lately we’ve become accustomed to seeing rocket boosters return to Earth and then land vertically, on their tails, ready to be serviced and flown again. (Much the same

majestic imagery thrilled sci-fi moviegoers in the 1950s.) Today, both SpaceX and Blue Origin are using these techniques, and a third startup, Relativity Space, is on the verge of joining them. Such reusable rocketry is already cutting the cost of access to space and, with other advances yet to come, will help make it possible for humanity to return to the moon and eventually to travel to Mars.

Vertical landings, too, have a long history, with the same ground being plowed many times by multiple research organizations. From 1993 to 1996 a booster named DCX, for

Delta Clipper Experimental, took off and landed vertically eight times at White Sands Missile Range. It flew to a height of only 2,500 meters, but it successfully negotiated the very tricky dynamics of landing a vertical cylinder on its end.

The key innovations that made all this possible happened 50 or more years ago. And those in turn built upon the

invention a century ago of liquid-fueled rockets that can be throttled up or down by pumping more or less fuel into a combustion chamber.