T.K. Jones, 82, Dies; Arms Official Saw Nuclear War as Survivable

By

SAM ROBERTSMAY 23, 2015

Continue reading the main story Share This Page

- Share

- Tweet

- Email

- More

- Save

Photo

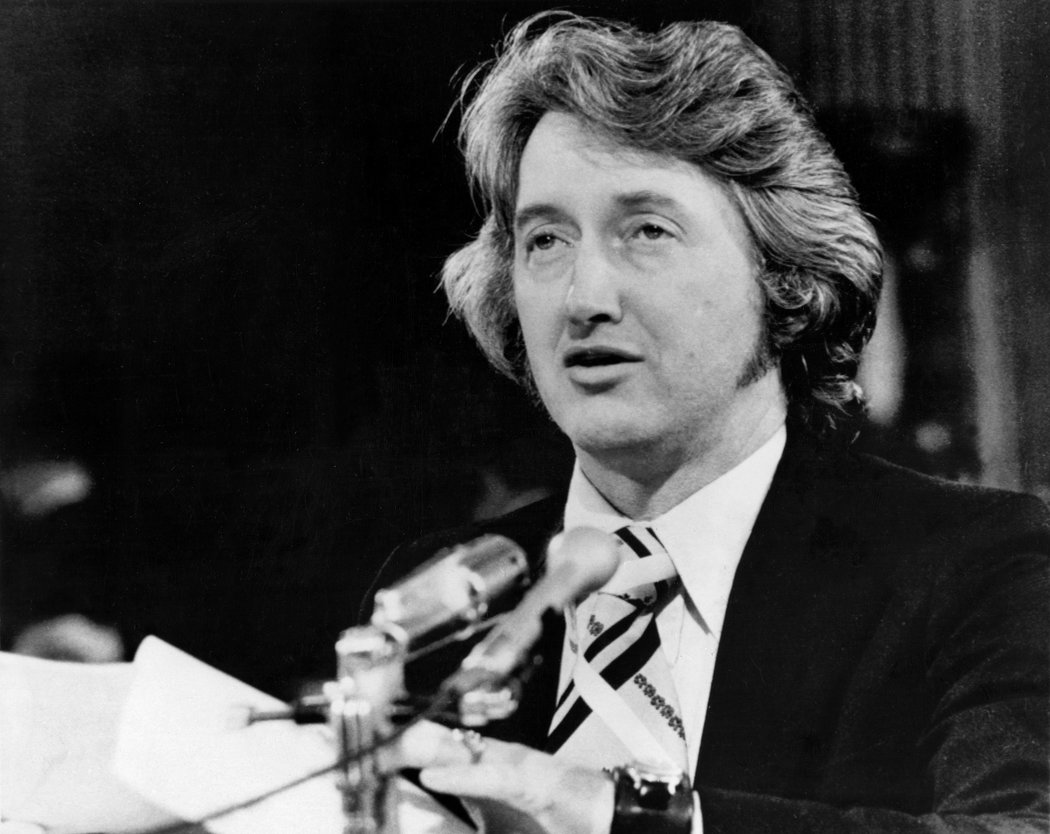

Thomas K. Jones in 1976. An American arms negotiator, he believed the Soviets were better prepared for a nuclear strike. Credit Associated Press

Thomas K. Jones, an American defense official and arms negotiator who turned Nikita Khrushchev’s defiant “We will bury you” threat on its head when he declared in 1982 that Americans could survive a Soviet nuclear attack by digging shelters — “If there are enough shovels to go around,” he said, “everybody’s going to make it” — died on May 15 in Bellevue, Wash. He was 82.

The cause was complications of Parkinson’s disease, his wife, Deborah, said.

His “enough shovels” assurance was largely derided, but his faith in the efficacy of civil defense, his certitude that the Soviets were better prepared to rebound from a nuclear strike and his fears that the United States was lagging in weapons development undergirded the Reagan administration’s aggressive missile defense strategy and its resolve during arms limitation talks to maintain America’s bomber superiority.

Mr. Jones, the deputy under secretary of defense for strategic and theater nuclear forces and a technical adviser to the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, was an acolyte of Paul Nitze, an architect of Cold War arms policy. Mr. Nitze, a deputy defense secretary under President Lyndon B. Johnson, co-founded Team B, the think tank whose assessment of America’s vulnerability to Soviet weapons — it later appeared to have been overstated — prompted an arms race that began in the waning days of Jimmy Carter’s administration and accelerated under Ronald Reagan.

Mr. Jones operated mostly below the radar until 1982 when, in an interview with Robert Scheer of The Los Angeles Times, he delivered his “enough shovels” civil defense prescription.

Continue reading the main story

Without adequate protection, he warned, “half the people in the country” would die in a nuclear attack, and it would take “a couple of generations” to recover. However, he was quoted as saying, “if we used the Russian methods for protecting both the people and the industrial means of production, recovery times could be two to four years.”

That the nation could survive a nuclear war — and therefore might be more inclined to engage in one — rattled Senate Democrats, who summoned Mr. Jones to elaborate. He failed to appear, three times; the Defense Department sent other officials instead. When the Democrats accused them of gagging Mr. Jones, the officials insisted that he did not speak for the department “on these matters.”

His comments prompted

an editorial in The New York Times, under the headline “The Dirt on T. K. Jones.”

“Who is the Thomas K. Jones who is saying those funny things about civil defense?” it began. “Is he only a character in ‘Doonesbury’? Did he once write lyrics for Tom Lehrer’s darker political ballads? Or is T. K., as he is known to friends, the peace movement’s mole inside the Reagan Administration?”

Mr. Jones finally appeared on Capitol Hill on March 31, 1982, joining the assistant secretary Richard N. Perle in appealing to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for more civil defense funding. Asked about his “enough shovels” remarks, Mr. Jones said they had been misinterpreted. Mr. Scheer, who later wrote a book titled “With Enough Shovels: Reagan, Bush and Nuclear War” (1982), said he had tape-recorded their interview.

“The tapes were transcribed by the transcription staff at The L.A. Times, and they are accurate as quoted in my book and writing for the paper,” Mr. Scheer said in an interview on Friday.

Mr. Scheer spoke to Mr. Jones in his Pentagon office and again at his home, on Mercer Island, Wash. “T. K may have sounded like a kook,” he said, “but he was hardly alone in the Pentagon and its allied industry.”

In the published interview, Mr. Scheer quoted Mr. Jones as saying, “You can make very good sheltering by taking the doors off your house, digging a trench, stacking the doors about two deep over that, covering it with plastic so that rainwater or something doesn’t screw up the glue in the door, then pile dirt over it.”

California Today

The news and stories that matter to Californians (and anyone else interested in the state), delivered weekday mornings.

Receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

Digging, he figured, would take about 10 hours, followed by installation of a ventilation pump and dealing with sanitation and supplies. Apartment dwellers were no problem, he said; they could be moved to rural areas.

“The second problem of the ’50s was we fell into that argument of: If you’ve got a shelter and your neighbor’s got a gun, how’s this going to be handled?” he continued. “Turns out with the Russian approach, if there are enough shovels to go around, everybody’s going to make it.”

Any inflated estimate of Soviet civil defenses suggested that the United States should invest more not only in protecting its citizens and industrial resources, but also in weapons capable of inflicting additional damage on the enemy.

Mr. Jones considered himself apolitical, but the response to his remarks split pretty much along ideological lines — between those who considered him a prophet whose predictions, translated into policy, intimidated the Soviets into ending the Cold War, and those who dismissed him as an unhinged hawk who evoked Dr. Strangelove.

In a 1984 book, “Ronald Reagan: The Politics of Symbolism,” the historian Robert Dallek wrote, “The belief that any such civil defense program could allow the country to survive a nuclear conflict encourages the administration to contemplate fighting such a war.” And in 2013 in Salon, the journalist Alexander Zaitchik

wrote that it was ironic that “the neocons were selling their vision of Soviet supremacy largely on the fantasy of a sophisticated Soviet civil defense program — which consisted of little more than dirt-covered doors.”

But in “Waging Nuclear Peace: The Technology and Politics of Nuclear Weapons” (1985), Robert Ehrlich, while warning against “overenthusiastic” claims, said that “realistic civil defense and crisis relocation could be effective.” And Richard F. Sincere Jr. wrote in 1983 in The Washington Times that while Mr. Jones was portrayed as “a wild-eyed maniac,” critics ignored the empirical data he had gathered, “which demonstrate that, with proper preparations, the devastation from

nuclear weapons can be significantly mitigated.”

Anyway, said Bruce G. Blair, a research scholar at the Program on Science and Global Security at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School, “by the mid-1980s and the rise of Gorbachev, Reagan switched gears and renounced the idea of fighting and winning a nuclear war, and he actually sought the total elimination of nuclear weapons.”

Thomas Kensington Jones was born in Tacoma, Wash., on June 30, 1932. He started working for what became Boeing Aerospace while attending the University of Washington’s School of Engineering and remained there after graduating. Except for his forays into government service, he spent his entire career at the company and retired in 1999.

At Boeing he worked on the Minuteman missile and on manned space and strategic bomber systems as the company’s program and product evaluation manager. In 1971, during the Nixon administration, he joined the defense secretary’s support group for the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks; he later became its deputy director and senior technical adviser.

In addition to his wife, the former Deborah Benedetto, Mr. Jones is survived by his daughters, Kerin Jones, Kelli Wick, Alicia Calderon and Mindy Shivers; his sons, Kevin Jones and George L. Richardson Jr.; four grandsons; and a brother, Jason.

Tai jopa Putinin hallinto.

Tai jopa Putinin hallinto.