NyTimesin Uutisessa kuvasta oli korostettu käytännössä yksi rivi. Linkki siihen Iltalehden uutisessa. Alemmassa kuvassa tummempi alue. Ei se miljoonakaupunkiin paljon ole, mutta samaan tautiin ainakin kohtalaisesti. Lieneekö haudattu muualle, vaikea sanoa.Varmasti Iranissa on kuollut ihmisiä valtavasti, mutta en ymmärrä mitä tuon satelliittikuvan hautausmaalta pitäisi todistaa?

Before

Katso liite: 38129

After

Katso liite: 38130

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Epidemiat maailmalla

- Viestiketjun aloittaja Tvälups

- Aloitus PVM

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Norwegian pyytää välitöntä apua valtiolta.

Suuri sääli jos kaatuu.

On kyllä sääli jos menee nurin. Itse olen aina käyttänyt Norwegiania Osloon ja Tukholmaan matkustaessa.

Itse myös käytän kun lapsiperheen rahat riittävät pelkästään siihen.On kyllä sääli jos menee nurin. Itse olen aina käyttänyt Norwegiania Osloon ja Tukholmaan matkustaessa.

Tanska ja Puola sulkevat rajansa koronaviruksen takia

Tanska ja Puola sulkevat rajansa koronaviruksen takia. Asiasta kertoivat maiden pääministerit.

Entäs ne ihmisoikeudet? Asylum jne

Tanska ja Puola sulkevat rajansa koronaviruksen takia

Tanska ja Puola sulkevat rajansa koronaviruksen takia. Asiasta kertoivat maiden pääministerit.www.is.fi

Koronavirus on tappanut Italiassa 250 ihmistä viime vuorokauden aikana

Julkaistu: 19:52

Italiassa 250 ihmistä on kuollut 24 tunnin aikana koronavirukseen, kertovat maan viranomaiset.

Virallisten lukujen mukaan kyseessä on suurin kuolonuhrien määrä yksittäisen päivän aikana Italiassa.

Yhteensä Italiassa yli 1 200 ihmistä on nyt kuollut koronavirukseen. Tartuntoja on todettu lähes 18 000. Nousua torstai-illasta on yli 2 500.

www.is.fi

www.is.fi

Julkaistu: 19:52

Italiassa 250 ihmistä on kuollut 24 tunnin aikana koronavirukseen, kertovat maan viranomaiset.

Virallisten lukujen mukaan kyseessä on suurin kuolonuhrien määrä yksittäisen päivän aikana Italiassa.

Yhteensä Italiassa yli 1 200 ihmistä on nyt kuollut koronavirukseen. Tartuntoja on todettu lähes 18 000. Nousua torstai-illasta on yli 2 500.

Koronavirus on tappanut Italiassa 250 ihmistä viime vuorokauden aikana

Italiassa 250 ihmistä on kuollut 24 tunnin aikana koronavirukseen, kertovat maan viranomaiset.

Vähän isomman kuvan maalailua.

Huhta

Greatest Leader

Hyysärin palatsin aulassa tarjoillaan varmaan sinä tilanteessa kahvia ja kakkua. Muutama vuosi siitä eteenpäin niin tulevat kaipaamaan Trumpia ja tätä rauhan kautta joka hänen vallassa ollessaan on ollut.

Vain 499 vieraalle kerrallaan!

Huhta

Greatest Leader

Niin ja ilmasto kiittää.

Myös valaat kiittävät.

From 9/11, a Lesson on Whales, Noise and Stress

A brief halt to shipping after the terrorist attacks appears to have lowered whales’ stress levels, an ocean experiment suggests.

green.blogs.nytimes.com

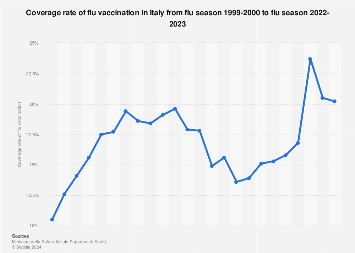

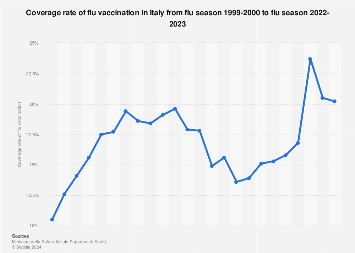

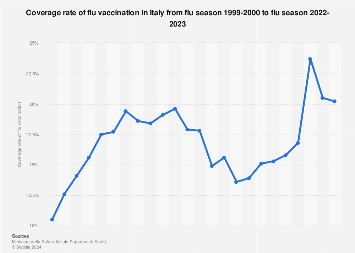

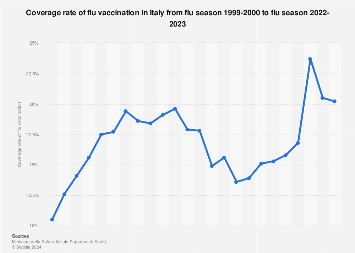

Tuli tässä sattumoisin mieleen ku mietin miksi Italiassa tuntuu porukkaa (vanhaa) kuolevan enempi kuin muualla vaikka kaiken järjen mukaan corona-viruskannassa ei pitäisi olla eroa (esim. Suomeen ja Itävaltaan tuodut tapaukset). Voisiko kuolematjohtua influenssan ja coronan yhteisvaikutuksesta? Flunssa kausi Italiassa on samanlainen kun viime vuonna joka oli pahin 14-vuoteen. Tammikuussa tauti riehui erityisesti pohjoisessa kuten Corona nyt... Voiko olla että riskiryhmään kuuluvat eivät yksinkertaisesti kestä kahta rajua tautia peräkkäin.

Influenssa rokote on kelvannut n. 15% kansasta. Italia on rokotevastainen maa kuten tuhkarokko keisseistä on nähty...

www.statista.com

www.statista.com

Influenssa rokote on kelvannut n. 15% kansasta. Italia on rokotevastainen maa kuten tuhkarokko keisseistä on nähty...

Italy: coverage rate of flu vaccination 1999-2024| Statista

The share of individuals getting vaccinated against flu in Italy reached the highest rate in the season 2020-2021, with the outbreak of COVID-19.

Sensei142

Majuri

Itse osaltani mietin italian perhekeskeisyyttä, vanhukset asuu saman katon alla nuorempien kanssa ja tauti nappaa sitten heikommat, voisko olla vaikutustaTuli tässä sattumoisin mieleen ku mietin miksi Italiassa tuntuu porukkaa (vanhaa) kuolevan enempi kuin muualla vaikka kaiken järjen mukaan corona-viruskannassa ei pitäisi olla eroa (esim. Suomeen ja Itävaltaan tuodut tapaukset). Voisiko kuolematjohtua influenssan ja coronan yhteisvaikutuksesta? Flunssa kausi Italiassa on samanlainen kun viime vuonna joka oli pahin 14-vuoteen. Tammikuussa tauti riehui erityisesti pohjoisessa kuten Corona nyt... Voiko olla että riskiryhmään kuuluvat eivät yksinkertaisesti kestä kahta rajua tautia peräkkäin.

Influenssa rokote on kelvannut n. 15% kansasta. Italia on rokotevastainen maa kuten tuhkarokko keisseistä on nähty...

Italy: coverage rate of flu vaccination 1999-2024| Statista

The share of individuals getting vaccinated against flu in Italy reached the highest rate in the season 2020-2021, with the outbreak of COVID-19.www.statista.com

USA:ssa tapahtuu nyt todella nopeasti päätösten osalta. Hätätila, sopimus demokraattien kanssa, palkalliset sairaslomat koronapotilaille, ilmaiset testit yms. "sosialismia". CDC (voiko sanoa: paikallinen THL?) on kompuroinut testikittien määrän kanssa, mikä tähän mennessä ollut yksi suurimpia ongelmia.

Vaikka USA:ssa on huonot lähtökohdat (OECD näkövinkkelistä) viruksen taltuttamiseen, niin ei pidä arvioida amerikkalaista kekseliäisyyttä, dynaamisuutta ja tiukan paikan tullen yhteen hiileen puhaltamista.

Vaikka USA:ssa on huonot lähtökohdat (OECD näkövinkkelistä) viruksen taltuttamiseen, niin ei pidä arvioida amerikkalaista kekseliäisyyttä, dynaamisuutta ja tiukan paikan tullen yhteen hiileen puhaltamista.

The coronavirus, first reported from Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019, has spread to more than 80 countries. Cases top 118,000; deaths exceed 4,200. Governments, desperate to manage the flow of patients into health services, have employed wildly different measures. Belgium, France, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, amongst others, have closed all their schools. Italy is under total lockdown. The United States has banned flights from most of Europe. India has effectively closed its borders to all foreign visitors. Israel is quarantining all arrivals from abroad for 14 days.

The UK, which now has 590 cases, will take a different path to the rest of the world. It has been hesitant to deploy the four social distancing measures available to it – school closures, limitation of movement, restrictions of mass gatherings and quarantine. And prime minister Boris Johnson announced last night that the NHS will no longer test those self isolating at home, and that the country will avoid lockdowns.

Yet there is an anomaly amongst the chaos that the virus is reaping across the world that may give the UK pause for thought. China, which was recording more than 3,000 cases as recently as February, reported just 26 new cases on Thursday.

Compare this stat to Italy, which reported 213 deaths from the virus, and more than 2,000 new cases on Wednesday – or even the UK, which reported 83 – and the decline appears even more remarkable. The WHO has recognised it as such, praising China’s response, while a new study in the journal Science shows that the country’s travel lockdown may have sharply slowed the virus’s global spread.

What, then, should the UK, in the early stages of its own epidemic, learn from China’s success?

What the world can learn from China’s coronavirus lockdown

China’s quarantine has nearly wiped out new coronavirus cases in the country. But as the virus spreads across the world, a global lockdown is unlikely to be effective

If you are judging the country’s mood by the toilet paper and pasta on the shelves in major supermarkets, it feels like the end of days. First the hoards came for surgical face masks, hand sanitisers and flu medicine. Then they came for bog roll, fusilli, UHT milk and baked beans.

As quickly as supermarkets restocked, essentials flew off the shelves. So far, there have been no serious shortages. But experts believe that this is only a matter of time – and that if demand continues like this, we may be a couple of weeks away from supermarkets and manufacturers running out of reserve stock.

John Perry, managing director of consulting firm SCALA, says that the UK’s supply chain has been streamlined over the last few years to a three-week manufacturing model. Put simply, if we all start to stock up like this, the system will eventually buckle.

Grocers have systems to be able to see what the sales are and to be able to send the requirement back down the chain to call the product forward and in turn to call it from the manufacturers. That can all happen very quickly. “Typically a retailer can restock overnight from their own distribution centre. Within two days they can get more product from the manufacturer to restock their distribution centre. But quite clearly what that places is huge surges in demand,” Perry says.

How Brexit prepared supermarkets for our coronavirus stockpiling

As global panic-buying of essentials like toilet paper, tinned goods and pasta continues, the only hope for supermarkets is for us all to calm down

Huhta

Greatest Leader

Mielenkiintoinen Twitter-ketju brittiprofessorin pohdintaa UK:n strategiasta - annetaan koronaviruksen levitä "hallitusti" valtaväestöön että saadaan laumasuoja, suojellaan riskiryhmät.

Suomella ja THL:llä samankaltainen linja?

Pastean tänne oikeaan ketjuun.

On kyllä täysin hullu suunnitelma eikä mitään mahdollisuutta toimia, ellei riskiryhmiä jotenkin suojata. Ja miten suojattaisiin? Diabeetikoita, keuhkosairaita, sydän- ja verisuonitauteja sairastavia jne. on iso osuus väestöstä. Ilmeisesti siellä on päätetty karsia NHS:n vakioasiakkaat pois taudin verukkeella.

Minä ennemmin rajoittaisin tautia. Jos koko yhteiskuntaa ei voikaan sulkea, niin koulut ja yliopistot (opetustoiminta) voi laittaa kiinni hyvin pienellä vahingolla. Samaten massatapahtumat voidaan kieltää ilman suurta vahinkoa, jääkiekko-ottelun näkee kotisohvaltakin. Jos oikein pitkälle on tarve mennä, niin voidaan sulkea myös ei-välttämättömiä palveluita, joiden tartuntapotentiaali on suuri ja yhteiskunnallinen välttämättömyys pieni: kuntosaleja, uimahalleja, parturiliikkeitä, ravintoloita, krääsäkauppoja ja vastaavia.

Samaten kuumemittaukset on otettava käyttöön työpaikoilla, kaupoissa, liikennevälineissä ja vastaavissa paikoissa. Ei sataprosenttinen keino, mutta rajoittaa epidemian leviämistä, kun sairaat eivät liikuskele täysin vapaasti.

Samoin julkisilla paikoilla tulee asettaa pakolliseksi suusuojuksen käyttö. Näitä simppeleitä kuminauhallisia kangaslerpakkeita pystytään kyllä tarvittaessa valmistamaan suuria määriä, kun toimeen ryhdytään heti ja konvertoidaan mm. kaupalliset ompelimot tähän käyttöön. Käyttäjää eivät ehkä suojele, mutta muita käyttäjältä, ja se on ihan riittävä peruste.

Todennäköisesti aika pienilläkin teoilla saadaan aikaan paljon. 10 prosenttia vähemmän sosiaalista kanssakäymistä, ja tautihuippu miltei puolittuu. 25 prosenttia vähemmän sosiaalista kanssakäymistä, ja tautihuippua ei synny melkein ollenkaan.

Maidan

Respected Leader

Mielenkiintoinen näkemys. Miksi italialaiset ovat rokotevastainen maa, katolilaisuuden takia?Tuli tässä sattumoisin mieleen ku mietin miksi Italiassa tuntuu porukkaa (vanhaa) kuolevan enempi kuin muualla vaikka kaiken järjen mukaan corona-viruskannassa ei pitäisi olla eroa (esim. Suomeen ja Itävaltaan tuodut tapaukset). Voisiko kuolematjohtua influenssan ja coronan yhteisvaikutuksesta? Flunssa kausi Italiassa on samanlainen kun viime vuonna joka oli pahin 14-vuoteen. Tammikuussa tauti riehui erityisesti pohjoisessa kuten Corona nyt... Voiko olla että riskiryhmään kuuluvat eivät yksinkertaisesti kestä kahta rajua tautia peräkkäin.

Influenssa rokote on kelvannut n. 15% kansasta. Italia on rokotevastainen maa kuten tuhkarokko keisseistä on nähty...

Italy: coverage rate of flu vaccination 1999-2024| Statista

The share of individuals getting vaccinated against flu in Italy reached the highest rate in the season 2020-2021, with the outbreak of COVID-19.www.statista.com

Gundjajevin ortodoksisessa kirkossa Venäjällä rokotevaisuus on normi, muun sekopäisyyden lisäksi. Luulin että ovat ainoat

murhahimoiset.

Huhta

Greatest Leader

Mielenkiintoinen näkemys. Miksi italialaiset ovat rokotevastainen maa, katolilaisuuden takia?

Gundjajevin ortodoksisessa kirkossa Venäjällä rokotevaisuus on normi, muun sekopäisyyden lisäksi. Luulin että ovat ainoat

murhahimoiset.

Pölhöpopulistit ovat heiluttaneet kansalaisten uskoa viranomaisiin. Ja sitten on päälle autismikortti - tuomioistuin päätti vuonna 2012, että MPR-rokote aiheutti autismin yhdelle lapselle.

Why Italy's U-turn on mandatory vaccination shocks the scientific community

An amendment from Italy's anti-establishment government that removes mandatory vaccination for schoolchildren is sending shock waves through the country's medical community.edition.cnn.com

Italians' trust in the efficacy and safety of vaccinations was affected by an infamous ruling in 2012 from a Rimini court that established a link between autism and the combined measles, mumps and rubella vaccination, experts say. While the ruling was overturned three years later, it helped anti-vaccination theories to spread in Italy -- and globally.

Others maintain that the skepticism about vaccines is in line with a more general lack of trust in Italy's institutions, a sentiment that the populist Five Star Movement was able to channel in its political agenda, winning support at the latest general elections.

Rise of Italian populist parties buoys anti-vaccine movement

Backlash against sportsman’s post about his young daughter highlights lingering distrust

In a high-profile case in 2012, a court in Rimini awarded compensation to the family of an autistic child after ruling that the child’s autism had probably been caused by the MMR jab. The judgment was quashed on appeal three years later.

Grillo is a member of the Five Star Movement (M5S), whose founder, Beppe Grillo (no relation), has said in the past that vaccines can be as dangerous as the diseases they protect against. In 2015 the party proposed a law against vaccinations, citing “the link between vaccinations and specific illnesses such as leukaemia, poisoning, inflammation, immunodepression, inheritable genetic mutations, cancer, autism and allergies.”

Before the election in March, M5S changed course slightly. The party leader, Luigi Di Maio, said he was not anti-vaccination but against obliging parents to have their children injected. Last week Giulia Grillo, who is pregnant with her first child, said she would have her baby vaccinated.

But M5S’s coalition ally, the League, could end up dictating how the debate is resolved. Matteo Salvini, the party’s leader and deputy prime minister, recently said the requirement for 10 vaccines was “too much”.

“It’s difficult to know what [the government] will do because within M5S there are different positions – some are close to the scientific position, others are opposed,” said Burioni. “The League doesn’t leave me feeling very optimistic but judging before they’ve done anything would be premature.”

Maidan

Respected Leader

Nyt ei oikein auennut lihavoitu osuus.Samoin julkisilla paikoilla tulee asettaa pakolliseksi suusuojuksen käyttö. Näitä simppeleitä kuminauhallisia kangaslerpakkeita pystytään kyllä tarvittaessa valmistamaan suuria määriä, kun toimeen ryhdytään heti ja konvertoidaan mm. kaupalliset ompelimot tähän käyttöön. Käyttäjää eivät ehkä suojele, mutta muita käyttäjältä, ja se on ihan riittävä peruste.