Maksumuurin takana. :/

Joulu on jakamisen aikaa, joten ottakaa koko kirjoitus.Kykenisitkö referoimaan oleellisen?

Outlook improves but offshore wind is not yet subsidy-free

The next challenge is to drive down the costs of intermittency

"For the first time renewables are expected to come online below market prices and without additional subsidy on bills, meaning a better deal for consumers,” said the UK’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy earlier this month.

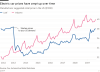

It was greeting the announcement that the latest wave of offshore wind farms will require guaranteed prices of between just £39.65 and £41.61 per MWh to get built.

At a time of escalating climate despondency, with the Swedish teenage activist Greta Thunberg earning cheers last week when she ticked off a UN conference over the developed world’s complacent inertia, the decline in offshore wind prices is a genuine shaft of light through the gloom.

As recently as 2014, the UK government was handing out contracts worth £150/MWh, although these were not struck through competitive auctions. Subsequent tenders saw the price drop to £110/MWh in 2015, and then a further startling fall to £57.50 two years ago.

The latest drop takes the price below the government’s estimate for wholesale electricity prices when the farms come online from 2023. Which brings us to the really big news, which is the idea that offshore wind farms could be built without subsidy assistance at all.

Now that would really change the weather for renewables, potentially unleashing construction on a scale that would allow these technologies to play a much larger role in the power network. This is something that will incidentally be necessary if the country is to meet the targets set out in the Committee on Climate Change’s plan to get to “net zero” carbon emissions by the middle of the century. It envisages a system with 75GW of offshore capacity, as against an expected 18GW by 2024.

But is it really true that offshore wind is on course for this by going “subsidy free”? Not yet — at least not in the sense of dispensing with public assistance.

The 6GW of projects agreed recently may have strike prices lower than current estimates of future wholesale prices, but they still enjoy the benefit of guaranteed prices financed by the consumer, and a ready market for whatever power they produce. It’s a privilege only offered to a few favoured power technologies.

And that is not the only leg-up they receive. While wind may be abundant in the British Isles, nature also dictates that its output is intermittent. Which in turn imposes further charges, such as paying to switch off turbines when the wind is blowing too hard and calling up back-up power when it’s not blowing hard enough. Or funding the extra grid and transmission costs of running electricity from remote offshore sites to the places where it’s needed. These expenses are presently passed on to all customers, rather than fborne by renewable operators themselves.

Quite how big such “system costs” are is something that is disputed. But what is accepted is that they go up as more renewables come on to the overall system. A recent study from the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency suggested a rise from $7 (£5.68)/MWh at 10 per cent penetration to as much as $50 (£40.63) at very high levels. Add that latter figure to the £39.65 struck recently and the latest round of contracts does not look quite so competitive, although it still beats the £92.50/MWh for the Hinkley Point nuclear scheme. But the key point is: we just don’t know.

The next challenge then is to squeeze down the cost of intermittency. That’s not impossible. Proponents of renewables point to fixes, such as using AI-enabled appliances to limit the need for back-up, or more battery storage to enable wind farms to bridge gaps when nature will not play ball.

But that will need investment — and plenty of it. Take battery storage for instance. A recent study by the French utility company EDF (which has a foot in both nuclear and renewables) suggested that to build the battery storage necessary to supply Britain with power for just one week would presently cost £1tn.

The logical way forward would be to force renewables investors to bear the costs of their intermittency. If they are right about the fixes, they should be willing to take the risk. One way would be to take up the solution proposed by the economist Dieter Helm who wants to make renewables bid to deliver so-called “firm power” to the grid — thus buying in any nature-induced shortfall.

In the short term this might actually increase the visible subsidy requirement, as renewables operators have to price in the back-up. But it would at least signal to the public the real cost consequences of choosing different power technologies.

No less importantly, it would give the renewables sector a strong incentive to bear down on the cost of intermittency, which is vital. For until that dwindles, subsidies won’t disappear.