ONLINE ANALYSIS

18th June 2025

Israel’s attack and the limits of Iran’s missile strategy

Israel’s attack on Iran has exposed critical weaknesses in Tehran’s broader military strategy. While Iran still has untapped shorter-range capabilities it could deploy in its immediate neighbourhood, its depleted medium-range missile arsenal and weakened regional allies leave it with limited options for retaliation against Israel.

On 13 June 2025, following months of escalating tension and limited reciprocal strikes, Israel launched a large-scale attack on Iran’s nuclear programme and conventional military capabilities. In addition to nuclear facilities, the initial strike waves appear to have prioritised time-sensitive targets such as nuclear scientists, senior military commanders including Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Commander Hossein Salami and IRGC Aerospace Force Commander Amir Ali Hajizadeh, as well as air defence systems.

As part of the opening campaign, Israel targeted ballistic missile assets expected to play a central role in Iran’s anticipated retaliation. Strikes were conducted against major missile sites in western Iran, including underground bases in Khorramabad, Kermanshah, and Tabriz. In parallel, Israel

employed small uninhabited aerial vehicles (UAVs), reportedly smuggled into Iran by its intelligence services, against air defence systems and road-mobile ballistic missile launchers. Israel has long pioneered the use of such UAVs for stand-off sabotage,

previously deploying explosive-laden drones against critical nodes in Iran’s nuclear and missile programmes. The operational freedom gained through the destruction of Iranian air defences then enabled the Israeli Air Force to conduct dynamic targeting of

mobile missile launchers using more conventional strike assets. According to the Israeli Air Force, the service

destroyed about 120 launchers as of 16 June, representing roughly a third of Iran’s pre-war inventory.

Iran’s response

Iran’s first response came on the night of 13 June with a strike involving

approximately 150 missiles launched in two waves, followed in the subsequent days by smaller barrages encompassing

tens of missiles, with the total number of ballistic missiles fired

standing at 370 as of 16 June. Notably, the scale of any individual strike or tightly-grouped salvos remained well below the 200 missiles launched in a single night during

Operation True Promise 2 on 1 October 2024. According to

press reports, the limited scope of the initial attack may have been the result of Israeli interdiction efforts, with Iran originally planning to launch up to 1,000 missiles but being forced to scale down the operation. In addition to Israel’s kinetic strikes on missile launchers and bases, targeted assassinations of key Iranian commanders likely disrupted command and control. This disruption may have been further exacerbated by operational elements not yet fully known, such as cyber attacks, electronic warfare or strikes against communications infrastructure.

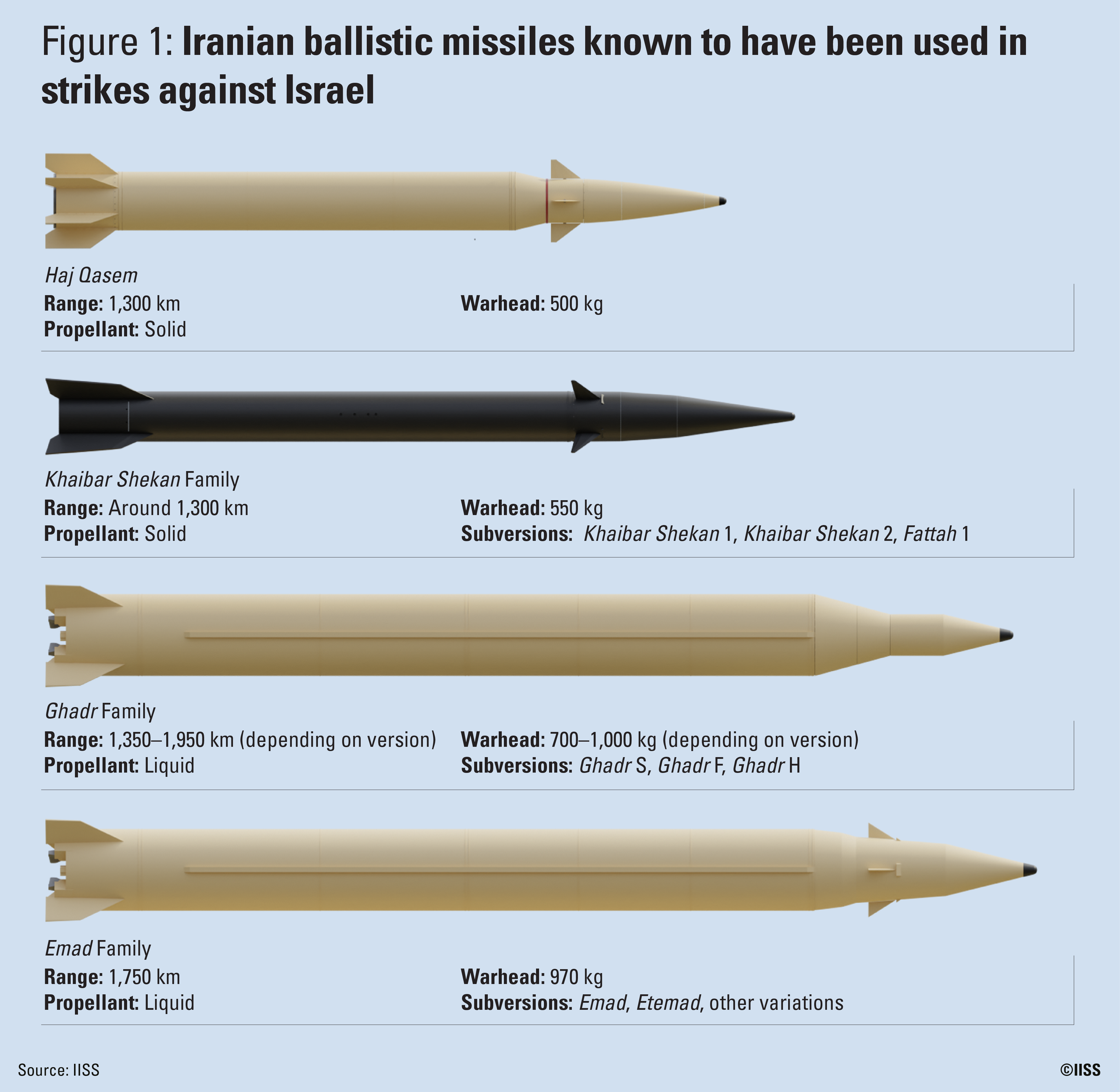

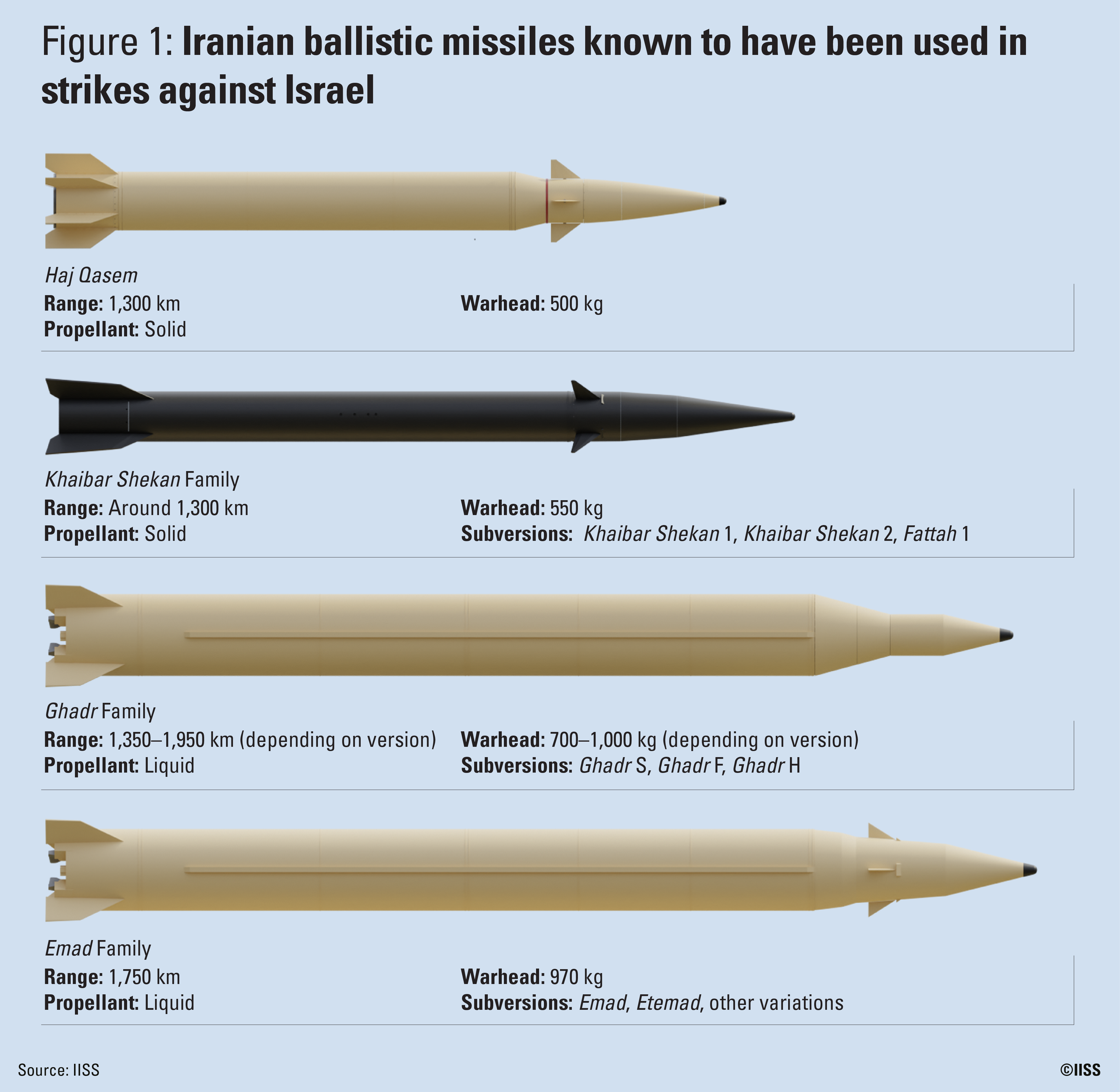

Beyond the quantitative dimension, there is no indication of a qualitative improvement in Iranian missile and UAV attacks compared with the October 2024 strike. Visual evidence of missile debris and Israeli left-of-launch strikes points to the use of

Emad,

Haj Qasem,

Khaibar Shekan, or Fattah 1 systems, all of which were already employed in last year’s attack. In addition to ballistic missiles, Iran also launched more than 100 one-way attack UAVs, including the

Shahed 136,

Arash 2 and an enlarged version of the

Shahed 101. Most of these appear to have been successfully intercepted.

Despite the smaller scale of the current ballistic missile attacks compared with those in 2024, Israeli casualties have been

significantly higher, with at least 23 killed and more than 600 injured to date. This outcome appears to be less a function of the quantity or quality of missiles used and more the result of target selection. While the 2024 strikes focused primarily on remote military installations such as Nevatim air base, recent attacks have also targeted sites in more densely populated urban areas, including Tel Aviv, Haifa and Tamra. This may, at least partially, indicate a shift by Iran toward countervalue targeting as a means of raising the costs imposed by its missile strikes. During the 2024 campaign, Iran’s medium-range ballistic missiles demonstrated limited accuracy, restricting their value in counterforce roles. Ballistic missiles hitting population centres could also be the result of Iran perceiving Israeli attacks against targets in densely populated areas as representing attacks on its cities and attempting to respond in kind. Israel, meanwhile, might have chosen to assign a higher priority to the protection of more strategic installations to assist with weapons stock management, thereby reducing the level of protection in large Israeli cities.

Assessing Iran’s remaining ballistic threat

The scale of the remaining missile threat from Iran remains uncertain and depends on several variables that are currently unknown. Chief among them is the size of Iran’s ballistic missile stockpile. In 2022,

United States’ Central Command estimates placed the arsenal at approximately 3,000 missiles, although this would include short-range ballistic missiles with insufficient range to reach Israel. More

recent Israeli assessments suggest a figure closer to 2,000 operational missiles. This would allow Iran to conduct only a limited number of large-scale barrages aimed at overwhelming Israeli missile defences. Moreover, this estimate does not account for ongoing Israeli operations targeting launchers, storage facilities and missile bases, which are likely to reduce Iran’s available inventory further.

Tehran’s options for replenishing its missile arsenal are limited. Before the current campaign, the US

assessed Iran’s ballistic missile production capacity to be approximately 50 missiles per month. Although this represents a significant production rate, it remains insufficient to sustain Iran’s current rate of fire. Israel also appears to be

expanding its operations to include direct strikes on Iran’s missile production infrastructure. Iran will, therefore, need to carefully calibrate its use of a limited missile arsenal for the duration and intensity of the conflict.

The other key variable in assessing the threat posed by Iran’s remaining missile arsenal is the size of Israel’s

Arrow 2 and

Arrow 3 interceptor stockpiles, as well as the interception rates these systems have demonstrated against Iranian missiles. Both figures remain unknown. Israel’s missile defence is

reinforced by direct US support, including the deployment of two

Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) batteries on Israeli territory and the presence of

Aegis-equipped vessels with advanced ballistic missile defence capabilities. This US support provides Israel with additional arsenal depth.

Potential escalation pathways

Iran may now seek new options for imposing costs on Israel or its American ally. One would be for Iran to target Israeli critical infrastructure, which often has a larger geographical footprint than military assets, making it easier to hit with the current generation of Iranian ballistic missiles. Iran appears to have already employed this approach, notably with its attack on the

Haifa refinery on the second day of the conflict. Another course of action would be for Iran to draw on its largely unexpended arsenal of more accurate short-range ballistic missiles to strike petrochemical facilities or US military bases in the Gulf region. These options, however, carry significant risks. Striking energy infrastructure would endanger Iran’s recently improved ties with Gulf states, while attacks on US forces would risk triggering direct American involvement in the conflict. Iran also still possesses a significant arsenal of anti-ship missiles that could be used to attack commercial shipping in the Gulf, the Gulf of Oman and, to a lesser extent, the Arabian Sea. Iran has

issued threats to close the Strait of Hormuz.

The limits of Iran’s deterrence strategy

While Iran faces significant immediate challenges in the use of its missile forces, their employment already indicates a broader failure of its military strategy. Despite substantial efforts in recent years to strengthen its air defences, Iran has always primarily relied on deterrence by punishment through the credible threat of significant retaliation. In the absence of an effective air force, missiles have served as the primary instrument for delivering such reprisals.

Lebanese Hizbullah’s weakening as a result of Israeli attacks in 2024 removed a key element from that strategy, as the group’s large rocket and missile arsenal, enabled by the proximity of Lebanon to Israel, ceased to be a significant factor. While Yemen’s Houthis have managed to cause severe disruption to shipping in the Red Sea and have targeted Israel with ballistic missiles, their geographical distance from Israel and relatively small arsenal prevents them from serving as a strategic deterrent comparable to Hizbullah. The limited effectiveness of Iran’s missile barrages in April and October 2024, which failed to cause significant damage or casualties, further eroded its deterrence posture. Israeli counterstrikes in late October then disabled the Russian-supplied

S-300 system, Iran’s most advanced air defence capability, and weakened Iran’s already fragile capability to deter by denial. These developments helped pave the way for Israel’s current large-scale campaign.

Iran’s deterrence strategy, however, not only relied on the scale and sophistication of its missile arsenal but also on its ability to accurately gauge the risk tolerance and pain thresholds of its adversaries. The missile deterrent credibility of Iran and the ‘Axis of Resistance’ was based on the assumption that the costs imposed by its use would be sufficient to deter aggression. The parameters of this equation shifted rapidly after the Hamas-led 7 October 2023 attacks, as Israel began to perceive the regional conflict in existential terms, adapted to a prolonged state of war and saw its tolerance for risk increase markedly. As a result, even in the absence of major changes in military capability, long-standing deterrence relationships began to break down. This was evident in the case of Hizbullah, whose deterrence relationship with Israel all but collapsed in 2024 despite no significant change in its strategic arsenal.

Today, with Iranian capabilities degraded and exposed as insufficient over the past year, and with the Israeli leadership, at least for the time being, accepting the risks of ballistic missile strikes on its population centres, the deterrence balance between Israel and Iran is unravelling at an even faster pace. Whether Israel’s elevated risk tolerance will endure in the face of more painful strikes remains to be seen.

AUTHOR

! Miten sionismi muka edisti antisemitismiä idässä? Hiukan ristiriitaista.

! Miten sionismi muka edisti antisemitismiä idässä? Hiukan ristiriitaista.