LinkkiMaailman suurin amfibiolentokone, kiinalainen AG600 on tehnyt ensilentonsa. Kone nousi ilmaan Zhuhain lentokentältä, Guangdongin maakunnasta, joka sijaitsee Etelä-Kiinan meren rannalla.

Kone lensi meren yllä noin tunnin ja palasi kentälle, missä sitä vastaanottamassa oli riemuitseva väkijoukko ja sotaisaa musiikkia soittanut torvisoittokunta.

AG600-koneen on valmistanut Kiinan valtio-omisteinen lentokoneyhtiö Aviation Industry of China (AVIC). Koneen kehitystyö vei yhdeksän vuotta.

AG600 on tarkoitettu saarikohteisiin suunnattuihin kuljetuksiin ja myös viranomaisvoiman käyttöön, kertoo Kiinan valtion tiedotuskanava

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

LinkkiFierce monsoons and razor-edged reefs have proved deadly for Filipino seafarers for centuries, but there are more modern dangers lurking in the ocean for a crew of adventurers planning to sail the 600 miles to China in boats constructed with techniques that date to AD320.

“My greatest fear is to sail at night, because you can be run over by big ships,” said Arturo Valdez, 69, who is leading the mission. Without advanced navigation equipment, the only way his team will spot oil tankers is with their eyes. “We cannot even be seen on their radar because we are made of wood.”

Valdez heads a crew of about 30 who plan to leave Manila this spring in three 18-metre boats made of hardwood planks, colourful sails and just a small roofed area that shades them from the sun. The round trip will take about a month, and there is no toilet on board.

The balangays were made by boat builders from the southern Philippines using skills passed from one generation to the next.

The crew plans to recreate historical trade and migration routes in commemoration of a journey launched in 1417 by the Filipino sultan Paduka Batara, who set sail to pay tribute to Ming dynasty rulers.

Though he made it to China, the sultan fell ill and died. His wife and children remained and were granted land and citizenship, and thousands of their descendants remain there to this day.

Valdez hopes his voyage will be luckier than the sultan’s. To stay on course, he has enlisted the help of locals skilled in celestial navigation.

Many of the team are mountaineers who led an expedition to conquer Mount Everest, including Carina Dayondon, one of three women to make history when they became the first Filipinas to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain.

Onko se sitten ihan mahdoton ajatus pystyttää masto jonka päässä joku tutkaheijastin?“We cannot even be seen on their radar because we are made of wood.”

Onko se sitten ihan mahdoton ajatus pystyttää masto jonka päässä joku tutkaheijastin?

Ei tietenkään. Itse ottaisin tuon etuna, en takapakkina.

LinkkiA new Chinese undersea surveillance network is gathering oceanographic data stretching from the Western Pacific into the Indian Ocean, according to new reporting from the South China Morning Post. The network appears to be part of a much broader Chinese effort to improve its undersea warfare capabilities and erode the advantage that the United States’ advanced submarines provide it.

Earlier reporting on a part of this network covering the East and South China Seas emphasized its scientific mission while acknowledging it would contribute to China’s national defense. The network merges data collected by buoys, ships, satellites, and unmanned underwater gliders for analysis and use by the Chinese navy.

The United States also operates unmanned underwater gliders to collect oceanographic data, one of which was seized by the Chinese navy in December 2016 near the Philippines while it was being retrieved by a U.S. Navy oceanographic research vessel.

LinkkiFor 70 years the United States has dominated Southeast Asia with both hard and soft power — the capability to use economic or cultural influence to shape the preferences of others. Soft power underpins and makes possible robust hard power relationships. But some analysts and policymakers refuse to recognize that U.S. influence and its relationships in Southeast Asia are much shallower and more ephemeral than assumed.

Indeed, despite U.S. enticement and pressure, U.S. allies Australia, Japan, and the Philippines have so far declined U.S. requests to join its freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea against China’s claims. Indonesia has expressed disapproval over such U.S. “power projection” in the area. U.S. relations with Thailand have not been close since the military coup there in 2014 and Bangkok seems to be leaning toward China. Malaysia-U.S. relations have been brittle since the United States took a legal interest in Prime Minister Najib Razak’s international financial dealings. Even staunch U.S. strategic partner Singapore seems to be seeking a more neutral position between Washington and Beijing.

A recent example of this decline of U.S. soft power was the reaction of the Philippines regarding the January 17 USS Hopper freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) near Scarborough Shoal. The Shoal is claimed by China, Taiwan, and the Philippines. The U.S. Navy guided missile destroyer sailed through the 12 nautical mile territorial sea around the disputed feature. The Hopper’s transit was in innocent passage, which is generally considered legal (if somewhat provocative). China requires permission for innocent passage by warships and objected.

Laitan tänne koska osittain ne vehkeet mitä he ovat laittaneet saarille ovat suoraan rinnastettavissa tähän touhuun.

http://www.defenseone.com/technolog...te-should-scare-everyone/145718/?oref=d-riverChina’s evolving algorithmic surveillance system will rely on the security organs of the communist party-state to filter, collect, and analyze staggering volumes of data flowing across the internet. Justifying controls in the name of national security and social stability, China originally planned to develop what it called a “Golden Shield” surveillance system allowing easy access to local, national, and regional records on each citizen. This ambitious project has so far been mostly confined to a content-filtering Great Firewall, which prohibits foreign internet sites including Google, Facebook, and The New York Times. According to Freedom House, China’s level of internet freedom is already the worst on the planet. Now, the Communist Party of China is finally building the extensive, multilevel data-gathering system it has dreamed of for decades.

While the Chinese government has long scrutinized individual citizens for evidence of disloyalty to the regime, only now is it beginning to develop comprehensive, constantly updated, and granular records on each citizen’s political persuasions, comments, associations, and even consumer habits. The new social credit system under development will consolidate reams of records from private companies and government bureaucracies into a single “citizen score” for each Chinese citizen. In its comprehensive 2014 planning outline, the CCP explains a goal of “keep[ing] trust and constraints against breaking trust.” While the system is voluntary for now, it will be mandatory by 2020. Already, 100,000 Chinese citizens have posted on social media about high scores on a “Sesame Credit” app operated by Alibaba, in a private-sector precursor to the proposed government system. The massive e-commerce conglomerate claims its app is only tracking users’ financial and credit behavior, but promises to offer a “holistic rating of character.” It is not hard to imagine many Chinese boasting soon about their official scores.

While it isn’t yet clear what data will be considered, commentators are already speculating that the scope of the system will be alarmingly wide. The planned “citizen credit” score will likely weigh far more data than the Western fico score, which helps lenders make fast and reliable decisions on whether to extend financial credit. While the latter simply tracks whether you’ve paid back your debts and managed your money well, experts on China and internet privacy have speculated—based on the vast amounts of online shopping data mined by the government without regard for consumer privacy—that your Chinese credit score could be higher if you buy items the regime likes—like diapers—and lower if you buy ones it doesn’t, like video games or alcohol. Well beyond the realm of online consumer purchasing, your political involvement could also heavily affect your score: Posting political opinions without prior permission or even posting true news that the Chinese government dislikes could decrease your rank.

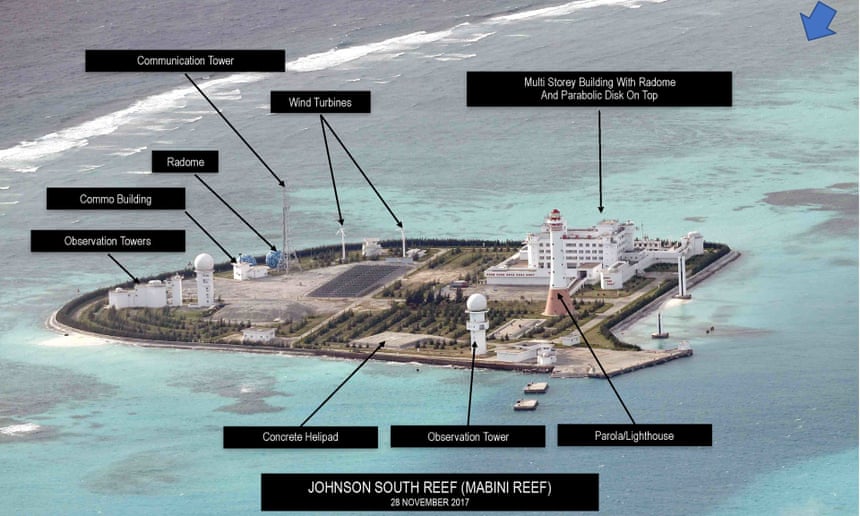

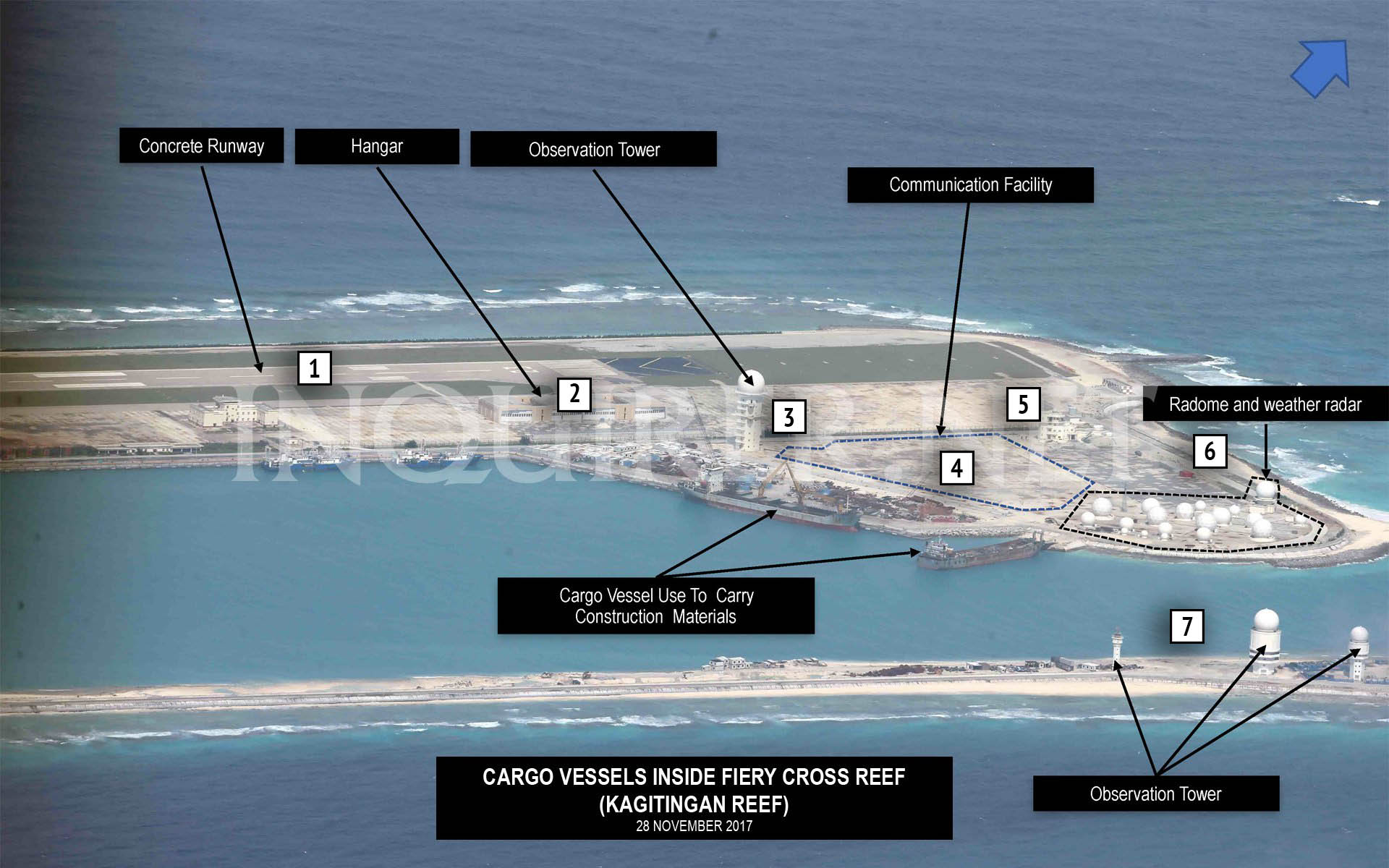

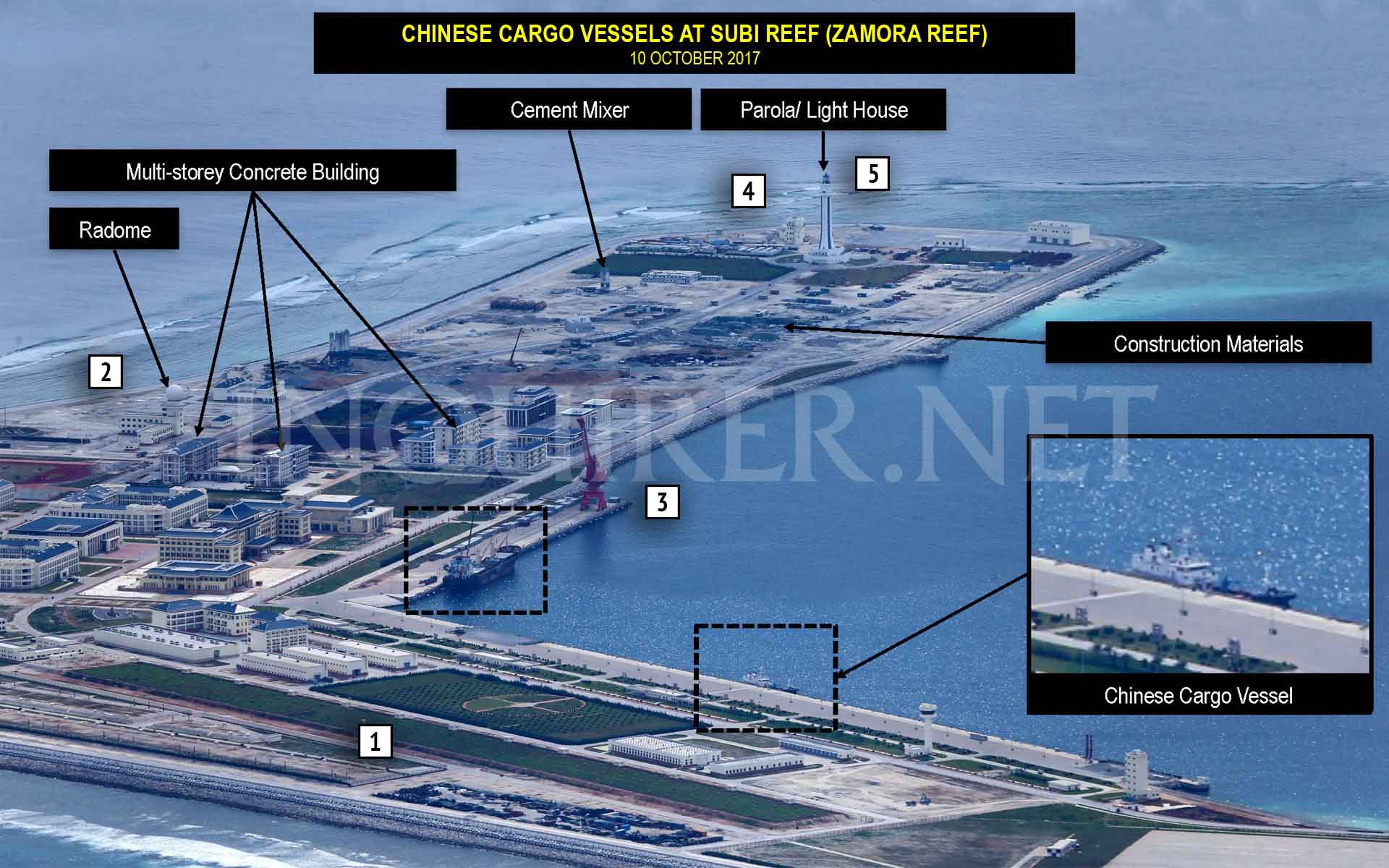

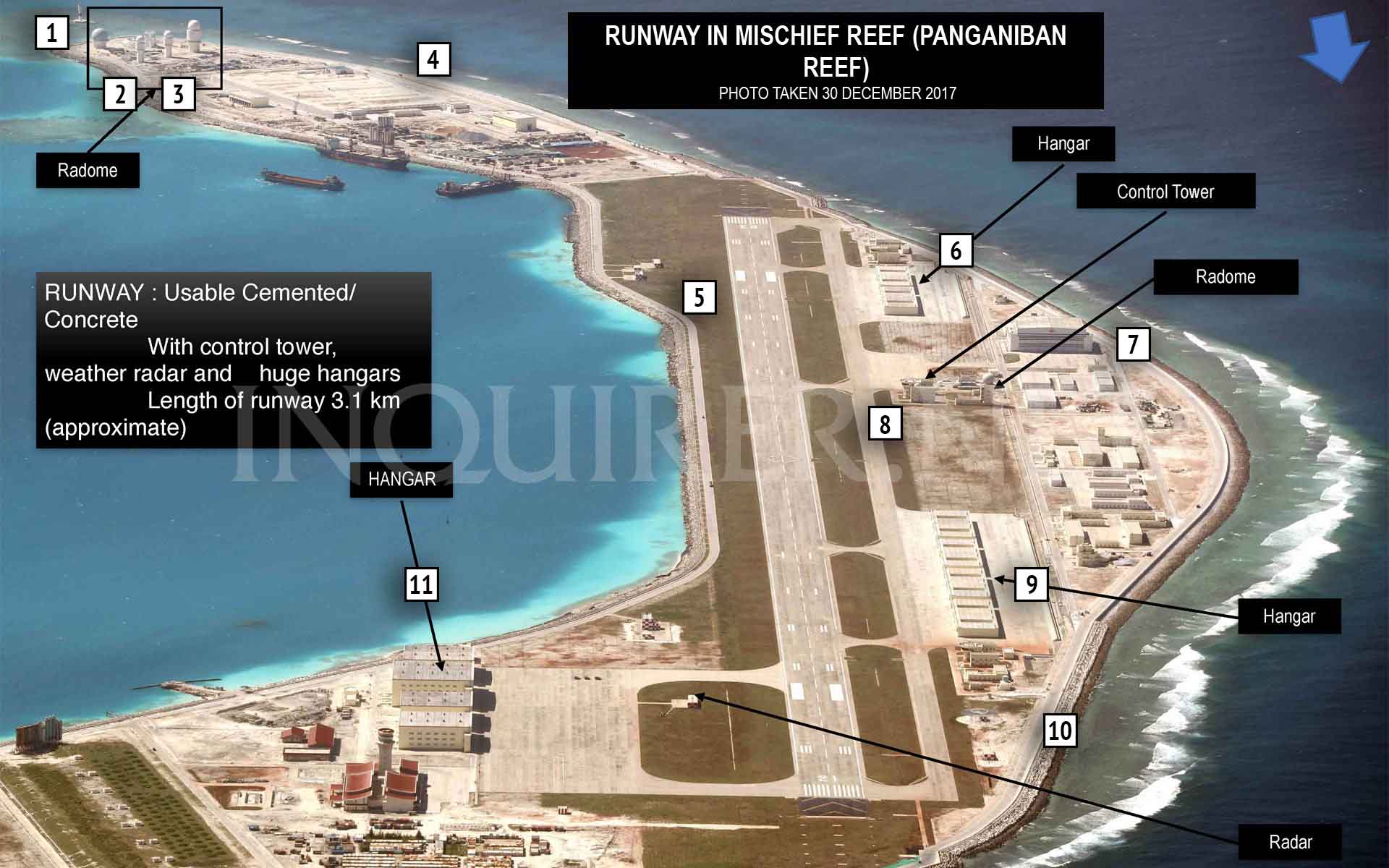

Beijing has been accused of building “island fortresses” in the South China Sea after a newspaper in the Philippines obtained aerial photographs offering what experts called the most detailed glimpse yet of China’s militarisation of the waterway.

The Philippine Daily Inquirer said the surveillance photographs – passed to its reporters by an unnamed source – were mostly taken between June and December last year and showed Chinese construction activities across the disputed Spratly archipelago between the Philippines and Vietnam.

Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam have overlapping claims in the region.

The Inquirer said the images showed an “unrestrained” building campaign designed to project Chinese power across the resource-rich shipping route through which trillions of dollars of global trade flows each year.

Kiina taitaa toistaiseksi olla ainoa Venäjän ulkopuolinen maa, joka lennättää su-35:sia.

http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/China_to_Develop_Sea_Based_Missile_Interceptors_999.htmlChina is planning to develop a sea-based missile defense launcher after completing a successful intercept of a ballistic missile in space from a ground-based system earlier this week, according to the South China Morning Post.

"China's sea-based anti-missile system aims to defend both its territory and overseas interests, because sea-based defense systems will be set up wherever its warships can go," analyst Song Zhongping said Tuesday, adding that "the first area it will target is the Asia-Pacific region and the Indian Ocean to protect its overseas interests."

Zhou Chenming, another analyst, told SCMP the developments are meant to show North Korea it is a relatively small nuclear power. The most recent missile interception occurred at a time when Pyongyang is gaining a stronger grip on how to launch nuclear weapons on ballistic missiles.

Further, the Indian military tested an Agni-V intercontinental ballistic missile in mid-January with sufficient range to reach anywhere in China.

However, Beijing may not have the capability to intercept US ICBMs yet.

"China's mid-course anti-missile system is powerful enough to shoot down missiles from North Korea and India, though it's not clear whether it could intercept an ICBM from the US if they start firing at each other," Zhou told SCMP.

The People's Liberation Army-Navy has rapidly expanded in recent years with the launch of the Liaoning, China's first aircraft carrier, in late 2016, before the construction of a second carrier in April 2017. At least four carrier groups are expected to be operating in the Chinese fleet by 2030.

Beijing has a strong interest in ensuring trading routes through the Indian Ocean and the Strait of Malacca are secure since 75 percent of its oil imports transit those waterways.

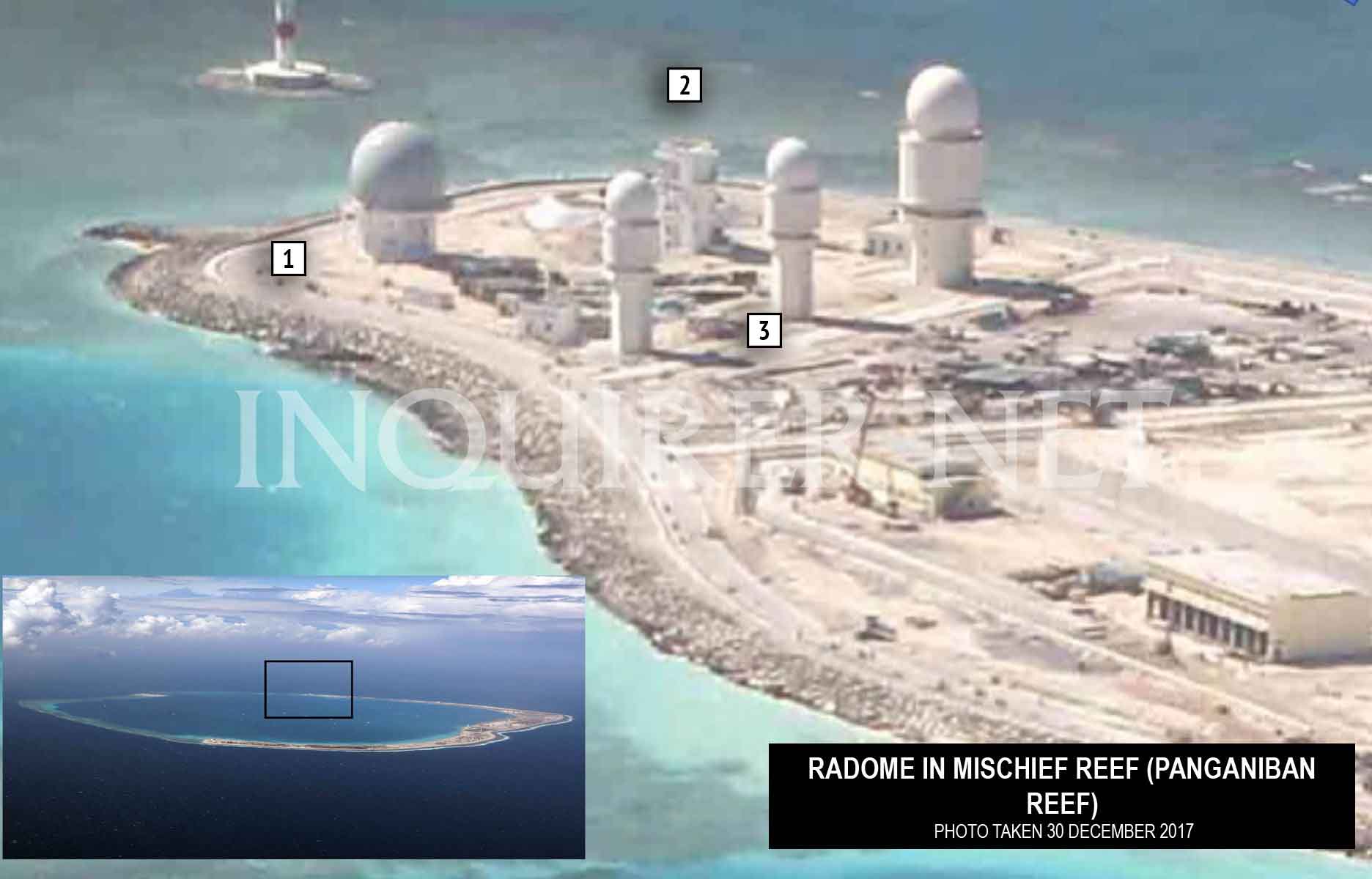

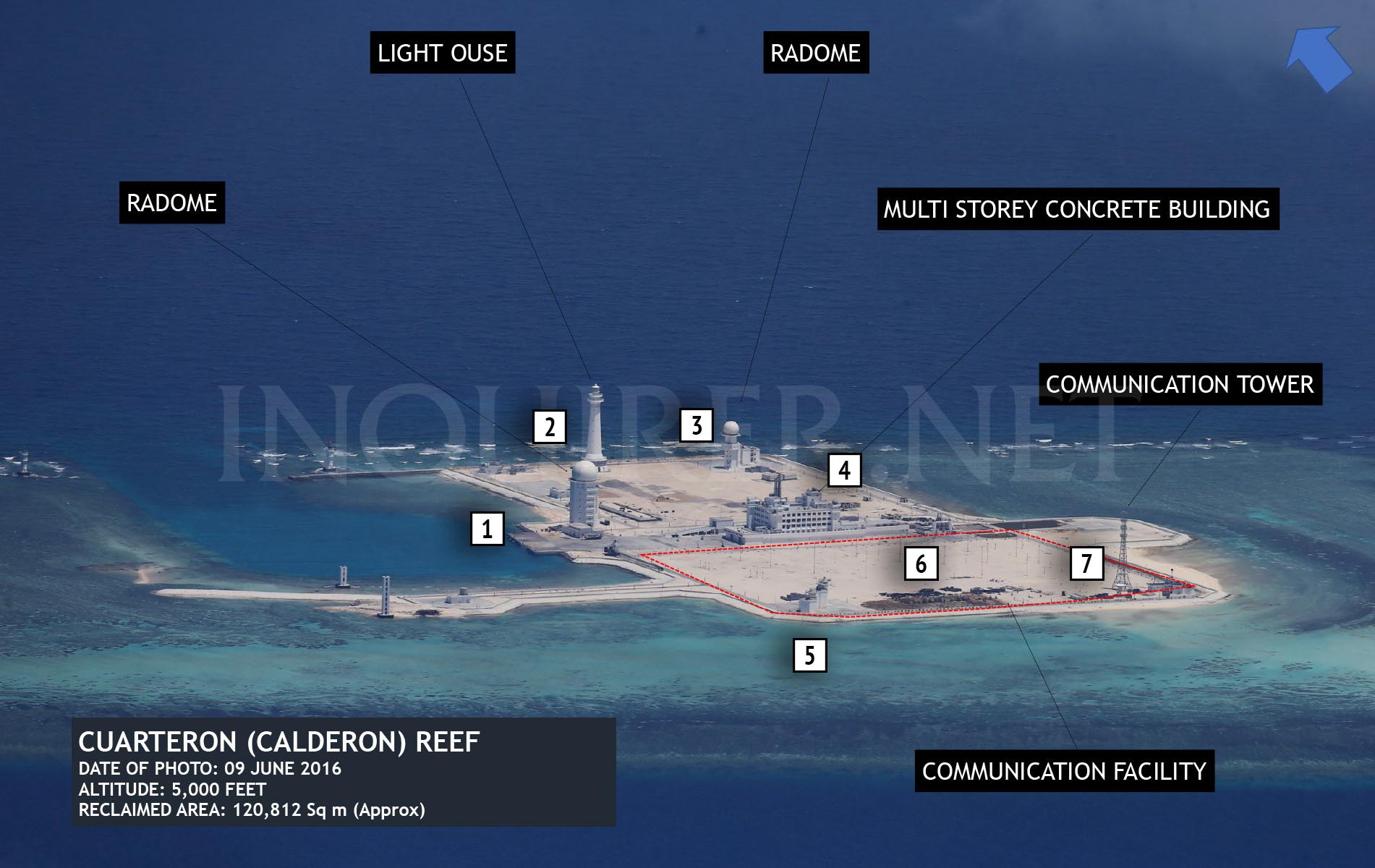

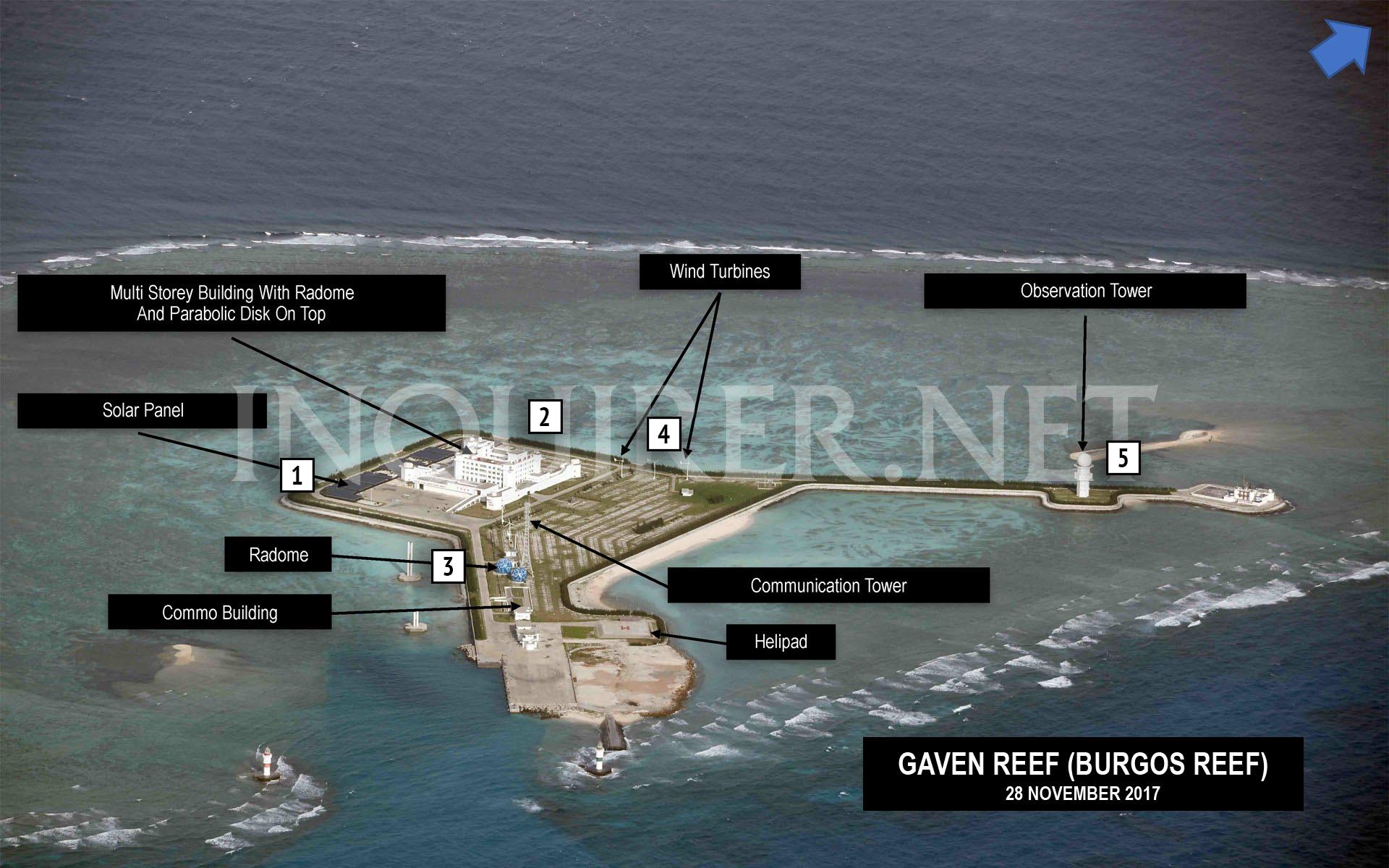

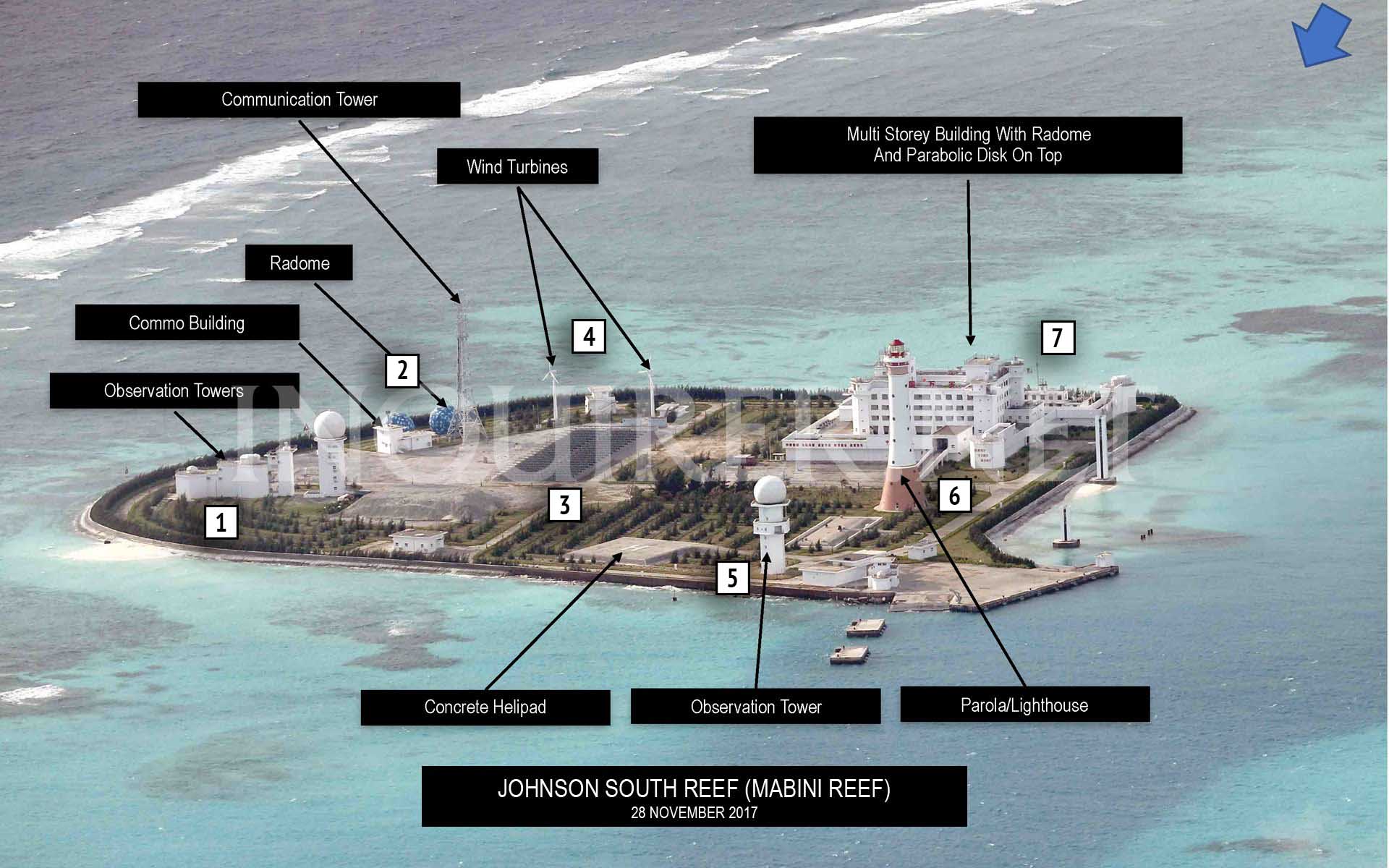

https://amti.csis.org/comparing-aerial-satellite-images-chinas-spratly-outposts/On February 5, the Philippine Daily Inquirer published a series of aerial photos of China’s seven outposts in the Spratly Islands. The photos, most of which were taken in late 2017 by an unspecified patrol aircraft from an altitude of 5,000 feet (1,500 meters), offered glimpses of Beijing’s military facilities at a level of detail rarely seen before. They also reinforced a message that AMTI delivered most recently in December: these artificial islands now host substantial, largely complete, air and naval bases, and new construction continues apace despite diplomatic overtures between China and its fellow claimants.

The aerial photos published by the Inquirer do not reveal any new capabilities on the artificial islands, but they do offer an important new perspective. These images communicate the relative sizes, and especially heights, of individual facilities more effectively than satellite imagery, though without the same ability to show the bases in their entirety. Comparing the aerial photos with AMTI’s most recently-available satellite imagery offers the best of both worlds, placing the former in context and lending the latter extra weight.

In the comparisons that follow, AMTI has used satellite images to highlight the direction from which each aerial photo was taken and then identifies the structures of note in both shots. Note that AMTI has not removed text on the aerial photos published by the Inquirer, but has added its identification of points of interest, represented by the boxed numbers on each image.

- One of the four point defense facilities built around the base in 2016. Similar point defenses exist on all of China’s artificial islands, sporting a combination of large guns (identified in one of the aerial photos of Johnson Reef as having 100-mm barrels) and probable close-in weapons systems (CIWS) emplacements.

- Hangars to accommodate four combat aircraft. Hangar space for another 20 combat aircraft and four larger hangars, capable of housing bombers, refueling tankers, and large transport aircraft, have been built farther south along the runway. All the hangars were completed in early 2017.

Viimeksi muokattu:

- Buried storage facilities, presumed to be for fuel, water, or other base necessities.

- A sensor/communications facility topped by a radome.

- Mobile shipping crane used to transfer cargo between ships and dock facility. In the satellite image, it can be seen at the middle of the dock next to several ships, while in the Inquirer photo it is at the eastern end of the dock.

- One of the four point defense facilities built around the base in 2016.

- A large lighthouse.

- The over 3,000-meter airstrip, completed in early 2016.

- Hangar space for 20 combat aircraft, completed by late 2016. Another four such hangars stand at the northern end of the runway.

- Four bigger hangars for large aircraft, completed in early 2017.

- Underground storage tunnels, likely for ammunition and other materiel, built during 2017. Identical buried storage facilities can be found on Fiery Cross and Subi Reefs.

- A high frequency “elephant cage” radar array, so called because the circular construction of the antennae resembles a tall fence.

- One of the four point defense facilities built around the base in 2016.

- Hardened structures with retractable roofs believed to be shelters for mobile missile launchers, completed in 2017. In the Inquirer photo, the top of the radome for the nearby tower, which will presumably be used for targeting, can be seen assembled on the ground, waiting for installation.

- A large sensor/communications facility topped by a radome, completed in 2017.

- One of the four point defense facilities built around the base in 2016.

- Three towers housing sensor/communications facilities topped by radomes, completed in 2017.

- Underground storage tunnels, likely for ammunition and other materiel, built during 2017. In the Inquirer’s photo, the tunnels are already buried, but AMTI’s satellite image shows the tunnels in an earlier, exposed state. Identical buried storage facilities have been constructed at Fiery Cross and Subi Reefs. There is also more underground storage built along the north side of Mischief (and at Fiery Cross and Subi).

- The base’s 3,000-meter runway, which has been complete since 2016.

- Hangar space for 8 combat aircraft, completed by late 2016.

- One of Mischief’s five hangars for larger aircraft, completed by late 2016.

- A sensor/communications facility topped by a radome paired with what is believed to be an administrative building for the airfield.

- Hangar space for 16 combat aircraft, completed by late 2016.

- An omnidirectional radio beacon for guiding inbound aircraft toward the airfield.

- A tall tower housing a sensor/communications facility topped by a radome, completed in early 2016.

- A lighthouse built in 2015, one of the first buildings constructed on the reef.

- One of two point defense emplacements completed in 2016.

- A large administrative building, similar to ones built on Gaven, Hughes, and Johnson Reefs.

- A second point defense emplacement, also completed in 2016.

- A large radar array, likely for high frequency over-the-horizon radar. Because the array consists of a grid of vertical poles, satellite images taken from directly overhead do a poor job of depicting the array. The Inquirer photos thus offer a much more enlightening perspective.

- A communications tower completed in 2015. The two blue radomes on the ground beside the tower in the satellite images do not appear in the aerial photos and were constructed in 2016.

- A solar panel array, constructed in tandem with the administrative building in 2015.

- The headquarters/administrative center on Gaven Reefs, built in 2015. The octagonal structures jutting out from each corner sport gun emplacements, which are covered up in the aerial Inquirer photos.

- A communications tower, with accompanying blue radomes. The tower went up in 2015, followed by the radomes in the first half of 2016.

- Three of six wind turbines on Gaven Reefs (the other three can be seen between the communication tower and administrative building). All six turbines appear to have been erected in 2015.

- A tall tower housing a sensor/communications facility topped by a radome, completed in 2016.

- A point defense emplacement, completed in 2016. The guns on the structure are covered up in the images.

- A communications tower with accompanying blue radomes. As on Cuarteron, Gaven, and Hughes Reefs, the tower was built in 2015 and the radomes completed in 2016.

- A solar panel array built in late 2015 or early 2016.

- Two wind turbines installed in late 2015.

- A tall tower housing a sensor/communications facility topped by a radome, completed in late 2015.

- A large lighthouse.

- The administrative/headquarters building, including point defenses, completed in early 2016.

http://warisboring.com/how-defensible-are-chinas-island-bases/China has built some islands in the South China Sea. Can it protect them?

During World War II Japan found that control of islands offered some strategic advantages, but not enough to force the United States to reduce each island individually. Moreover, over time the islands became a strategic liability, as Japan struggled to keep them supplied with food, fuel and equipment.

The islands of the SCS are conveniently located for China, but do they really represent an asset to China’s military? The answer is yes, but in an actual conflict the value would dwindle quickly.

All the military capabilities of China’s SCS islands depend upon secure communications with mainland China. Most of the islands constructed by China cannot support extensive logistics stockpiles, or keep those stockpiles safe from attack.

In a shooting war, the need to keep the islands supplied with fuel, equipment and munitions would quickly become a liability for presumably hard-stretched Chinese transport assets. Assuming that the PLAN and PLAAF would have little interest in pursuing risky, expensive efforts at resupplying islands under fire, the military value of the islands of the SCS would be a wasting asset during a conflict.

Unfortunately for China, the very nature of island warfare, and the nature of the specific formations that China has determined to support, make it difficult to keep installations in service in anything but the very short term.

Toisin sanoen Kiinanmeren saarilla pystytään projisoimaan voimaa, mutta pitkitetyssä konfliktissa niillä joutuu kärvistelemään varantojen huvetessa. Paras lääke tuohon tietysti on automatisointi, mutta ihmistyövoiman huvetessa, energian tuotanto ja varastointi nousevat ongelmiksi. Ei silti uskon että Kiina pystyy kehittämään vastauksia näihin kysymyksiin monien saarien ollessa hieman vaiheessa.

Viimeksi muokattu:

https://amti.csis.org/the-potential-of-the-quadrilateral/In Donald Trump’s first National Security Strategy (NSS), reference is given to the importance of increasing cooperation with Japan, Australia, and India. The idea is not new. The Quadrilateral Security Framework (also Quadrilateral Initiative; hereafter, the Quad), was initiated by Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe in 2006, but the idea fell apart after China vociferously objected to its formation, and a change of leadership in Australia led to a more ambivalent China policy. Prime Minister Abe has once again signaled support for the Quad, as did the United States’ NSS. At the same time, India and Australia are taking firmer stances against China. If the Quad’s time has finally come, what purpose would cooperation among these four countries serve in the contemporary strategic environment?

Kiinalainen näkökulma

https://amti.csis.org/chinese-perspective-rand-adiz-report/In November of last year, the RAND Corporation published a report titled In Line or Out of Order? China’s Approach to ADIZ in Theory and Practice, on the establishment of China’s East China Sea (ECS) Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) and the potential of a South China Sea ADIZ. Though comprehensive, the report suffers from a few common misperceptions of China’s ADIZ shared by many Western scholars and policymakers. These misperceptions, which touch on the fundamental nature of China’s ECS ADIZ, have received insufficient attention in the media and if left unclarified, could worsen distrust between governments and escalate tensions in the region. While this article does not seek to provide a comprehensive analysis of China’s strategy and motivations in the ECS, the author hopes that establishing the basic legal facts regarding the ECS ADIZ can facilitate constructive dialogue between the relevant actors going forward.