Huoranpenikat tappoivat eilisyön Lvin iskussa lähes koko perheen

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

The evidence suggests that on Ukraine, Putin simply is not persuadable; he is all in.

Totta, ainakin osittain. Mitä ilmeisimmin ryssä on paras disinformaation ja propagandan levittäjä, mitä tukee vankka kokemus ja vuosikymmenten aikana rakennettu verkosto käytännössä jokaiseen länsimaahan. Sekä tietysti täydellinen moraalin puute, joka sallii minkä tahansa toiminnan "tarkoitus pyhittää keinot" tyylillä, kun äitiryssän suojelu ja laajentaminen on se varsinainen tarkoitus.Foreign Affairs julkaisussa on kirjoitettu ajatuksia Ukrainan sodan suunnasta ja vaihtoehdoista. Artikkelin merkittävin teesi on se että Putin on sitoutunut tähän sotaan pitkän aikavälin strategisena tavoitteena ja ajatus siitä että "hänen mielensä tulisi muuttumaan" on syytä hylätä (artikkeli julkaistu 3.9.2024):

Putin Will Never Give Up in Ukraine

The West Can’t Change His Calculus—It Can Only Wait Him Out

By

September 3, 2024

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukra...content=&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter

Putin Will Never Give Up in Ukraine

The West Can’t Change His Calculus—It Can Only Wait Him Out

By Peter Schroeder

September 3, 2024

Katso liite: 103660

Russian President Vladimir Putin and members of his cabinet at a military parade in Saint Petersburg, July 2024

Vyacheslav Prokofyev / Sputnik / Reuters

-

Two and a half years after Russia invaded Ukraine, the United States’ strategy for ending the war remains the same: impose enough costs on Russia that its president, Vladimir Putin, will decide that he has no choice but to halt the conflict. In an effort to change his cost-benefit calculus, Washington has tried to find the sweet spot between supporting Ukraine and punishing Russia on the one hand, and reducing the risks of escalation on the other. As rational as this approach may appear, it rests on a faulty assumption: that Putin’s mind can be changed.

The evidence suggests that on Ukraine, Putin simply is not persuadable; he is all in. For him, preventing Ukraine from becoming a bastion that the West can use to threaten Russia is a strategic necessity. He has taken personal responsibility for achieving that outcome and likely judges it as worth nearly any cost. Trying to coerce him into giving up is a fruitless exercise that just wastes lives and resources.

There is only one viable option for ending the war in Ukraine on terms acceptable to the West and Kyiv: waiting Putin out. Under this approach, the United States would hold the line in Ukraine and maintain sanctions against Russia while minimizing the level of fighting and amount of resources expended until Putin dies or otherwise leaves office. Only then will there be a chance for a lasting peace in Ukraine.

PUTIN THE OPPORTUNIST?

When Putin ordered the invasion, it was a war of choice. There was no urgent security threat to Russia that necessitated a large-scale invasion of its neighbor. And it was distinctly Putin’s choice. Both William Burns, the director of the CIA, and Eric Green, the National Security Council’s senior director for Russia at the time, have noted how out of the loop other Russian officials seemed to be about Putin’s decision. Even at Putin’s stage-managed, televised meeting of his top security officials on the eve of the invasion, some participants didn’t seem to know exactly what to say. Russian elites eventually lined up behind him, but before February 2022, very few were pushing for a confrontation that would cost Russia so much and shatter relations with the West.

Because it is a war of choice, Putin has the power to stop it. Recognizing that the gambit proved to be harder than he anticipated, he could decide to cut his losses. The war is not existential for Russia, even if he has cast it that way rhetorically. Withdrawing Russian forces from Ukraine wouldn’t threaten the existence of the Russian state, nor would it likely even threaten his own rule. Putin has made sure that no potential successors have appeared on the horizon. The two who came closest to challenging him—the opposition leader Alexei Navalny and the mutineer Yevgeny Prigozhin—are now dead. The Kremlin has decades of experience shaping domestic narratives to bolster Putin. He could easily declare victory in Ukraine and launch an accompanying information campaign to justify his about-face.

But while Putin has the power to stop the war, would he ever be willing to do so? U.S. policymakers have largely answered that question in the affirmative, contending that with enough pressure, he could be forced to withdraw troops from Ukraine or at least negotiate a cease-fire. To change his calculus, Washington and its allies have imposed sweeping economic sanctions on Russia, given Ukraine military equipment and intelligence support, and isolated Moscow on the global stage.

Underneath this policy lies a belief that Putin is fundamentally an opportunist. He probes forward, and when he discovers weakness, he advances, but when he is met with strength, he withdraws. According to this view, Putin’s assault on Ukraine was driven by both his imperial ambitions and his perception of weakness in the West and in Ukraine. In President Joe Biden’s words, Putin has a “craven lust for land and power” and expected that after Russian forces invaded Ukraine, “NATO would fracture and divide.” If that is the diagnosis, then the right prescription is to show strength and resilience. Raise the costs of the war high enough, and he will eventually conclude that his opportunism isn’t paying off.

A SENSE OF INSECURITY

But Putin is not an opportunist, at least not on Ukraine. His most prominent international moves have not been opportunistic ploys to gain an advantage so much as preventive efforts to forestall perceived losses or retaliate against perceived provocations. Russia’s military action in Georgia in 2008 was both a response to that country’s attack on the separatist region of South Ossetia and an effort to avoid losing control of a territory it considered a point of leverage that could prevent Georgia’s integration with the West. When Putin seized Crimea in 2014, he worried about the loss of Russia’s naval base there. When he intervened in Syria in 2015, he worried about the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad, a Russia-friendly leader. And when he interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, he was responding to what he saw as U.S. efforts to undermine his position in Russia—namely, the United States’ public criticism of Russia’s elections in 2011–12 and the Panama Papers’ exposé of the secret financial dealings of his cronies in the spring of 2016.

If opportunism is motivating Putin in Ukraine—if the gambit is the product of his imperial avarice to gain Russian control of the country whenever the possibility presented itself—then his decidedly nonopportunistic approach to Ukraine from 2014 to 2021 needs to be explained. After Russia’s seizure of Crimea in March and April 2014, the Ukrainian government was in disarray. Yet rather than moving aggressively to seize additional territory, Putin chose to launch a low-level insurgency in eastern Ukraine that could be used as a bargaining chip to limit Kyiv’s foreign policy options. In September 2014, after Russian forces dealt a devastating defeat to Ukrainian forces in the city of Ilovaisk, Moscow probably could have advanced farther along the coast of the Sea of Azov, creating a land corridor from Crimea to Russia. Yet Putin instead opted for a political settlement, agreeing to the Minsk protocol.

Even after U.S. President Donald Trump took office, when it became clear that Washington was not inclined to help Kyiv, Putin still held back from launching a broader military attack or making any other attempt to expand Russian influence in Ukraine. Such missed chances sit uncomfortably alongside a view of Putin as a master opportunist.

Rather than an opportunistic war of aggression, the assault on Ukraine is better understood as an unjust preventive war launched to stop what Putin saw as a future security threat to Russia. In Putin’s view, Ukraine was turning into an anti-Russian state that, if not stopped, could be used by the West to undermine Russia’s domestic cohesion and host NATO forces that would threaten Russia itself. On some level, U.S. officials seem to understand this. As Avril Haines, the director of national intelligence, has said, “He saw Ukraine inexorably moving towards the West and towards NATO and away from Russia.”

While the invasion was not a crime of opportunity, it was a surprisingly risky move for Putin. He has tended to be risk-averse internationally, making calculated moves and minimizing the commitment of Russian resources. At just several thousand troops, Russia’s deployment to Syria has remained relatively small and mostly reliant on the Russian air force. When his fellow autocrat Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro seemed to be on the verge of overthrow in 2019, Putin deployed just a few hundred soldiers to help keep him in office. The war in Ukraine, by contrast, has cost Russia more than 100,000 soldiers’ lives and done untold damage to its economy and international standing.

That the war is so out of character with Putin’s normal risk calculus suggests that he made a strategic decision about Ukraine from which he is unwilling to back away. His decision to send the bulk of Russia’s army into Ukraine in 2022, and then mobilize more forces when his initial attack failed, demonstrates that he considers the war too important to fail. And for all the costs of his decision to invade, Putin likely thinks that the costs of inaction would have been higher—namely, that Russia would have been unable to prevent the emergence of a Western-aligned Ukraine that could serve as a springboard for a “color revolution” against Russia itself. If Putin doesn’t succeed now, he thinks, Russia is destined to incur those same costs. Given that this is likely how Putin is weighing the scenarios before him, Western pressure is unlikely to come anywhere close to coercing him into changing his mind and ending the war on terms acceptable to Kyiv and Washington.

THIS IS HOW IT ENDS

If Putin is unwilling to halt his assault on Ukraine, then the war can end in only one of two ways: either because Russia has lost the ability to continue its campaign or because Putin is no longer in power.

Bringing about the first outcome, by degrading Russia’s capabilities, is unrealistic. With Putin committed to the war and able to continue throwing soldiers and resources into the fight, the Russian military is unlikely to collapse. Defeating Putin on the ground in Ukraine would require a vast increase in munitions, but only in 2025 will the United States begin increasing production of necessary artillery shells, and even that uptick will not be enough to meet Ukraine’s battlefield requirements—to say nothing of the air defenses Ukraine could use. Ukraine will also need to continue sending soldiers into battle, and while the West can help train them, Western countries are not willing to commit their own troops. Adding to the difficulty, as over two years of war have shown, larger offensives are extremely difficult in the face of prepared defenses, especially now that drones and other surveillance technologies reduce the element of surprise for both sides.

That leaves the second route to ending the war: Putin’s exit from the Kremlin. Attempting to accelerate this process might look appealing, but it is an impractical idea. For decades, Washington has shown little ability to successfully manipulate Russian politics; trying to do so now would represent the triumph of hope over experience. Moreover, although Putin probably already thinks the United States is bent on ousting him, if it actually started taking steps to do so, he would very likely notice the change and see it as an escalation. In response, he might intensify Russian efforts to sow chaos in American society.

Given those risks, the best approach for Washington is to play the long game and wait for Putin to leave. It’s possible he may step down voluntarily or be pushed out; what is certain is that, at some point, he will die. Only once he is no longer in power can the real work of permanently resolving the war in Ukraine start.

PLAYING FOR TIME

Until then, Washington should focus on helping Ukraine hold the line and preventing further Russian military advances. It should continue to impose economic and diplomatic costs on Moscow but not expect them to have much effect; the main purpose of such pressure is to send the right message to U.S. allies and hold a point of leverage in reserve for a post-Putin Russia, all while avoiding domestic criticism. At the same time, Washington should husband its resources, expending them as efficiently as possible and convincing Kyiv to avoid large, wasteful offensives. Even Kyiv’s successful offensives to date—including the surprise attack into Russia’s Kursk region last month—have had little effect on the overall course of the conflict. It remains a war of attrition with no sign of a coming breakthrough for Ukraine.

When the Kursk offensive dissipates and Kyiv manages to arrest Russia’s progress in Donetsk, Washington should also support a cease-fire that halts the fighting. Although Putin could of course break any agreement, the benefits of a cease-fire outweigh the risks. A cease-fire would allow Ukraine to consolidate its defenses and train more soldiers, and the West could hedge its bets by continuing to supply the country with weapons. Most important, a cease-fire would prevent more soldiers and civilians from dying in a war that has no realistic end until Putin is gone.

When Putin does leave, however, Washington needs to be ready with a plan—one that not only resolves the war between Ukraine and Russia but also creates a positive framework for European security that eases military tensions, reduces the risk of conflict, and offers a vision that new Russian leaders in Moscow can buy into. That will require bold leadership, assertive diplomacy, and a willingness to compromise—in Moscow, Kyiv, Brussels, and Washington.

Since the invasion, the United States’ strategy toward the war in Ukraine has been characterized by wishful thinking. If only Washington can impose enough costs on Putin, it can convince him to halt the war in Ukraine. If only it can send enough weapons to Ukraine, Kyiv can push Russian forces out. After two and a half years, it should be clear that neither outcome is in the offing. The best approach is to play for time—holding the line in Ukraine, minimizing the costs for the United States, and preparing for the day Putin eventually leaves. This is an admittedly unsatisfying and politically unpalatable approach. But it is the only realistic option.

-

- PETER SCHROEDER is Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security. He was an analyst and a member of the Senior Analytic Service at the Central Intelligence Agency and from 2018 to 2022 served as Principal Deputy National Intelligence Officer for Russia and Eurasia at the National Intelligence Council.

-

Jos ei välitä artikkelin muusta analyysistä vaan haluaa tiivistetysti sen lopputuleman / toteaman, niin tässä avainkohta:

If Putin is unwilling to halt his assault on Ukraine, then the war can end in only one of two ways: either because Russia has lost the ability to continue its campaign or because Putin is no longer in power.

-

Hän tyrmää molemmat vaihtoehdot epätodennäköisinä.

Ensimmäinen vaihtoehto eli ryssän tappio vaatisi hänen arvionsa mukaan länneltä vahvempaa tukea, mistä ei ole merkkejä. Eikä yksikään maa ole valmis osallistumaan sotaan omilla joukoillaan. Samaan aikaan, hänen mukaansa, Venäjä kykenee kaatamaan sotaan kalustoa ja joukkoja sitä mukaa kun tappioita tulee. Hän nostaa myös esille sodan luonteen eli yllätyksen onnistuminen on vaikeaa tai jopa mahdotonta, mistä syystä sota on hidasta puskemista ja vahvojen asemien valtaamista - eli eteneminen on hidasta, vaikeaa ja tappiot suuria.

Toinen vaihtoehto eli Putinin vallastalähtö puolestaan on hankalaa, koska Putin on rakentanut järjestelmänsä 25 vuoden aikana. Hänen mukaansa Yhdysvalloilla on huono osaaminen "Venäjän sisäpolitiikkaan vaikuttamisessa" ja siten sellaisen yrittäminen tuskin johtaisi haluttuihin tuloksiin. Putin on myös varautunut tähän vaikuttamiseen, mikä vähentää onnistumisen todennäköisyyttä. Hän myös varoittaa että Putin saattaisi "kostaa" nämä yritykset lietsomalla sekasortoa Yhdysvalloissa.

-

JOTEN, jos nuo kaksi vaihtoehtoa ovat "epätodennäköisiä" niin mitä jää jäljelle?

Given those risks, the best approach for Washington is to play the long game and wait for Putin to leave. It’s possible he may step down voluntarily or be pushed out; what is certain is that, at some point, he will die. Only once he is no longer in power can the real work of permanently resolving the war in Ukraine start.

Pitkän pelin pelaaminen ja odottaminen. Putin saattaa astua syrjään vapaaehtoisesti tai pakotettuna, ja vaikka näin ei kävisikään, kukaan ei elä ikuisesti. Artikkelin kirjoittaja on vahvasti sitä mieltä että Ukrainan sodan "pysyvän ratkaisun" hakeminen ei ole mahdollista ennen kuin Putin on pois vallankahvasta.

-

Sinänsä hyvää pohdiskelua, mutta en ole kaikesta samaa mieltä.

En esimerkiksi usko että ryssä kykenee jatkamaan nykymuotoista sotaa loputtomiin. Tarkoitan tätä kaluston osalta, koska varastot tyhjenevät kovaa vauhtia eikä aito uustuotanto riitä paikkaamaan tätä. Samaan aikaan en usko että saisivat ostettua ulkomailta "tarvitsemiaan" sotakoneita. Toisaalta uskon että kykenevät jatkossakin hankkimaan sotilaita, joko vapaaehtoisina tai pakotettuina. Eli täten sodan luonne tulee muuttumaan, mikäli ei ole esim. panssarivaunuja tai IFV-vaunuja samassa määrin kuin aikaisemmin, mutta sota itsessään ei tule loppumaan.

Sodan luonteen muutos erilaiseksi voi antaa Ukrainalle tilaisuuksia edetä, mikäli puntit tasoittuvat kaluston osalta. Toki eteneminen olisi silloinkin hidasta ja tuskaisaa. Eikä ole varmuutta että Ukraina kykenisi tuohon.

Toisekseen artikkeli unohtaa yhden tärkeän vaihtoehdon: Putinin salamurha.

www.verkkouutiset.fi

www.verkkouutiset.fi

www.verkkouutiset.fi

www.verkkouutiset.fi

Ukraina torjuu yhä vähemmän ohjuksia – mikä neuvoksi? | Verkkouutiset

Ukraina torjuu yhä vähemmän ohjuksia – mikä neuvoksi? | Verkkouutisetwww.verkkouutiset.fi

Uutisessa unohtuu myös miten se örkki motivoidaan kuolemaan, eli raha. Absoluuttisesti mitaten ryssälässä on resursseja sotimisen jatkamiseen hyvin pitkäaikaisesti, vähintään vuosia. Mutta jotta vatniksita tulee örkki niin pitää tarjota luksusta. Siviilipuolen kulutustavarat ostetaan ulkoa. Samoin merkittävä osa puolustusteollisuuden kriitisistä osista. Nykyisellään sotiminen ylittää ryssän valuuttatulot joten jostain pitää tinkiä pian. Jos tingit kulutustavaroista niin elintaso romahtaa, jos tingit sotatarvikkeista niin sota hyytyy. Nyt ostetaan kummatkin ja valuuttavarannot alkaa loppua.Foreign Affairs julkaisussa on kirjoitettu ajatuksia Ukrainan sodan suunnasta ja vaihtoehdoista. Artikkelin merkittävin teesi on se että Putin on sitoutunut tähän sotaan pitkän aikavälin strategisena tavoitteena ja ajatus siitä että "hänen mielensä tulisi muuttumaan" on syytä hylätä (artikkeli julkaistu 3.9.2024):

Putin Will Never Give Up in Ukraine

The West Can’t Change His Calculus—It Can Only Wait Him Out

By

September 3, 2024

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukra...content=&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter

Putin Will Never Give Up in Ukraine

The West Can’t Change His Calculus—It Can Only Wait Him Out

By Peter Schroeder

September 3, 2024

Katso liite: 103660

Russian President Vladimir Putin and members of his cabinet at a military parade in Saint Petersburg, July 2024

Vyacheslav Prokofyev / Sputnik / Reuters

-

Two and a half years after Russia invaded Ukraine, the United States’ strategy for ending the war remains the same: impose enough costs on Russia that its president, Vladimir Putin, will decide that he has no choice but to halt the conflict. In an effort to change his cost-benefit calculus, Washington has tried to find the sweet spot between supporting Ukraine and punishing Russia on the one hand, and reducing the risks of escalation on the other. As rational as this approach may appear, it rests on a faulty assumption: that Putin’s mind can be changed.

The evidence suggests that on Ukraine, Putin simply is not persuadable; he is all in. For him, preventing Ukraine from becoming a bastion that the West can use to threaten Russia is a strategic necessity. He has taken personal responsibility for achieving that outcome and likely judges it as worth nearly any cost. Trying to coerce him into giving up is a fruitless exercise that just wastes lives and resources.

There is only one viable option for ending the war in Ukraine on terms acceptable to the West and Kyiv: waiting Putin out. Under this approach, the United States would hold the line in Ukraine and maintain sanctions against Russia while minimizing the level of fighting and amount of resources expended until Putin dies or otherwise leaves office. Only then will there be a chance for a lasting peace in Ukraine.

PUTIN THE OPPORTUNIST?

When Putin ordered the invasion, it was a war of choice. There was no urgent security threat to Russia that necessitated a large-scale invasion of its neighbor. And it was distinctly Putin’s choice. Both William Burns, the director of the CIA, and Eric Green, the National Security Council’s senior director for Russia at the time, have noted how out of the loop other Russian officials seemed to be about Putin’s decision. Even at Putin’s stage-managed, televised meeting of his top security officials on the eve of the invasion, some participants didn’t seem to know exactly what to say. Russian elites eventually lined up behind him, but before February 2022, very few were pushing for a confrontation that would cost Russia so much and shatter relations with the West.

Because it is a war of choice, Putin has the power to stop it. Recognizing that the gambit proved to be harder than he anticipated, he could decide to cut his losses. The war is not existential for Russia, even if he has cast it that way rhetorically. Withdrawing Russian forces from Ukraine wouldn’t threaten the existence of the Russian state, nor would it likely even threaten his own rule. Putin has made sure that no potential successors have appeared on the horizon. The two who came closest to challenging him—the opposition leader Alexei Navalny and the mutineer Yevgeny Prigozhin—are now dead. The Kremlin has decades of experience shaping domestic narratives to bolster Putin. He could easily declare victory in Ukraine and launch an accompanying information campaign to justify his about-face.

But while Putin has the power to stop the war, would he ever be willing to do so? U.S. policymakers have largely answered that question in the affirmative, contending that with enough pressure, he could be forced to withdraw troops from Ukraine or at least negotiate a cease-fire. To change his calculus, Washington and its allies have imposed sweeping economic sanctions on Russia, given Ukraine military equipment and intelligence support, and isolated Moscow on the global stage.

Underneath this policy lies a belief that Putin is fundamentally an opportunist. He probes forward, and when he discovers weakness, he advances, but when he is met with strength, he withdraws. According to this view, Putin’s assault on Ukraine was driven by both his imperial ambitions and his perception of weakness in the West and in Ukraine. In President Joe Biden’s words, Putin has a “craven lust for land and power” and expected that after Russian forces invaded Ukraine, “NATO would fracture and divide.” If that is the diagnosis, then the right prescription is to show strength and resilience. Raise the costs of the war high enough, and he will eventually conclude that his opportunism isn’t paying off.

A SENSE OF INSECURITY

But Putin is not an opportunist, at least not on Ukraine. His most prominent international moves have not been opportunistic ploys to gain an advantage so much as preventive efforts to forestall perceived losses or retaliate against perceived provocations. Russia’s military action in Georgia in 2008 was both a response to that country’s attack on the separatist region of South Ossetia and an effort to avoid losing control of a territory it considered a point of leverage that could prevent Georgia’s integration with the West. When Putin seized Crimea in 2014, he worried about the loss of Russia’s naval base there. When he intervened in Syria in 2015, he worried about the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad, a Russia-friendly leader. And when he interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, he was responding to what he saw as U.S. efforts to undermine his position in Russia—namely, the United States’ public criticism of Russia’s elections in 2011–12 and the Panama Papers’ exposé of the secret financial dealings of his cronies in the spring of 2016.

If opportunism is motivating Putin in Ukraine—if the gambit is the product of his imperial avarice to gain Russian control of the country whenever the possibility presented itself—then his decidedly nonopportunistic approach to Ukraine from 2014 to 2021 needs to be explained. After Russia’s seizure of Crimea in March and April 2014, the Ukrainian government was in disarray. Yet rather than moving aggressively to seize additional territory, Putin chose to launch a low-level insurgency in eastern Ukraine that could be used as a bargaining chip to limit Kyiv’s foreign policy options. In September 2014, after Russian forces dealt a devastating defeat to Ukrainian forces in the city of Ilovaisk, Moscow probably could have advanced farther along the coast of the Sea of Azov, creating a land corridor from Crimea to Russia. Yet Putin instead opted for a political settlement, agreeing to the Minsk protocol.

Even after U.S. President Donald Trump took office, when it became clear that Washington was not inclined to help Kyiv, Putin still held back from launching a broader military attack or making any other attempt to expand Russian influence in Ukraine. Such missed chances sit uncomfortably alongside a view of Putin as a master opportunist.

Rather than an opportunistic war of aggression, the assault on Ukraine is better understood as an unjust preventive war launched to stop what Putin saw as a future security threat to Russia. In Putin’s view, Ukraine was turning into an anti-Russian state that, if not stopped, could be used by the West to undermine Russia’s domestic cohesion and host NATO forces that would threaten Russia itself. On some level, U.S. officials seem to understand this. As Avril Haines, the director of national intelligence, has said, “He saw Ukraine inexorably moving towards the West and towards NATO and away from Russia.”

While the invasion was not a crime of opportunity, it was a surprisingly risky move for Putin. He has tended to be risk-averse internationally, making calculated moves and minimizing the commitment of Russian resources. At just several thousand troops, Russia’s deployment to Syria has remained relatively small and mostly reliant on the Russian air force. When his fellow autocrat Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro seemed to be on the verge of overthrow in 2019, Putin deployed just a few hundred soldiers to help keep him in office. The war in Ukraine, by contrast, has cost Russia more than 100,000 soldiers’ lives and done untold damage to its economy and international standing.

That the war is so out of character with Putin’s normal risk calculus suggests that he made a strategic decision about Ukraine from which he is unwilling to back away. His decision to send the bulk of Russia’s army into Ukraine in 2022, and then mobilize more forces when his initial attack failed, demonstrates that he considers the war too important to fail. And for all the costs of his decision to invade, Putin likely thinks that the costs of inaction would have been higher—namely, that Russia would have been unable to prevent the emergence of a Western-aligned Ukraine that could serve as a springboard for a “color revolution” against Russia itself. If Putin doesn’t succeed now, he thinks, Russia is destined to incur those same costs. Given that this is likely how Putin is weighing the scenarios before him, Western pressure is unlikely to come anywhere close to coercing him into changing his mind and ending the war on terms acceptable to Kyiv and Washington.

THIS IS HOW IT ENDS

If Putin is unwilling to halt his assault on Ukraine, then the war can end in only one of two ways: either because Russia has lost the ability to continue its campaign or because Putin is no longer in power.

Bringing about the first outcome, by degrading Russia’s capabilities, is unrealistic. With Putin committed to the war and able to continue throwing soldiers and resources into the fight, the Russian military is unlikely to collapse. Defeating Putin on the ground in Ukraine would require a vast increase in munitions, but only in 2025 will the United States begin increasing production of necessary artillery shells, and even that uptick will not be enough to meet Ukraine’s battlefield requirements—to say nothing of the air defenses Ukraine could use. Ukraine will also need to continue sending soldiers into battle, and while the West can help train them, Western countries are not willing to commit their own troops. Adding to the difficulty, as over two years of war have shown, larger offensives are extremely difficult in the face of prepared defenses, especially now that drones and other surveillance technologies reduce the element of surprise for both sides.

That leaves the second route to ending the war: Putin’s exit from the Kremlin. Attempting to accelerate this process might look appealing, but it is an impractical idea. For decades, Washington has shown little ability to successfully manipulate Russian politics; trying to do so now would represent the triumph of hope over experience. Moreover, although Putin probably already thinks the United States is bent on ousting him, if it actually started taking steps to do so, he would very likely notice the change and see it as an escalation. In response, he might intensify Russian efforts to sow chaos in American society.

Given those risks, the best approach for Washington is to play the long game and wait for Putin to leave. It’s possible he may step down voluntarily or be pushed out; what is certain is that, at some point, he will die. Only once he is no longer in power can the real work of permanently resolving the war in Ukraine start.

PLAYING FOR TIME

Until then, Washington should focus on helping Ukraine hold the line and preventing further Russian military advances. It should continue to impose economic and diplomatic costs on Moscow but not expect them to have much effect; the main purpose of such pressure is to send the right message to U.S. allies and hold a point of leverage in reserve for a post-Putin Russia, all while avoiding domestic criticism. At the same time, Washington should husband its resources, expending them as efficiently as possible and convincing Kyiv to avoid large, wasteful offensives. Even Kyiv’s successful offensives to date—including the surprise attack into Russia’s Kursk region last month—have had little effect on the overall course of the conflict. It remains a war of attrition with no sign of a coming breakthrough for Ukraine.

When the Kursk offensive dissipates and Kyiv manages to arrest Russia’s progress in Donetsk, Washington should also support a cease-fire that halts the fighting. Although Putin could of course break any agreement, the benefits of a cease-fire outweigh the risks. A cease-fire would allow Ukraine to consolidate its defenses and train more soldiers, and the West could hedge its bets by continuing to supply the country with weapons. Most important, a cease-fire would prevent more soldiers and civilians from dying in a war that has no realistic end until Putin is gone.

When Putin does leave, however, Washington needs to be ready with a plan—one that not only resolves the war between Ukraine and Russia but also creates a positive framework for European security that eases military tensions, reduces the risk of conflict, and offers a vision that new Russian leaders in Moscow can buy into. That will require bold leadership, assertive diplomacy, and a willingness to compromise—in Moscow, Kyiv, Brussels, and Washington.

Since the invasion, the United States’ strategy toward the war in Ukraine has been characterized by wishful thinking. If only Washington can impose enough costs on Putin, it can convince him to halt the war in Ukraine. If only it can send enough weapons to Ukraine, Kyiv can push Russian forces out. After two and a half years, it should be clear that neither outcome is in the offing. The best approach is to play for time—holding the line in Ukraine, minimizing the costs for the United States, and preparing for the day Putin eventually leaves. This is an admittedly unsatisfying and politically unpalatable approach. But it is the only realistic option.

-

- PETER SCHROEDER is Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security. He was an analyst and a member of the Senior Analytic Service at the Central Intelligence Agency and from 2018 to 2022 served as Principal Deputy National Intelligence Officer for Russia and Eurasia at the National Intelligence Council.

-

Jos ei välitä artikkelin muusta analyysistä vaan haluaa tiivistetysti sen lopputuleman / toteaman, niin tässä avainkohta:

If Putin is unwilling to halt his assault on Ukraine, then the war can end in only one of two ways: either because Russia has lost the ability to continue its campaign or because Putin is no longer in power.

-

Hän tyrmää molemmat vaihtoehdot epätodennäköisinä.

Ensimmäinen vaihtoehto eli ryssän tappio vaatisi hänen arvionsa mukaan länneltä vahvempaa tukea, mistä ei ole merkkejä. Eikä yksikään maa ole valmis osallistumaan sotaan omilla joukoillaan. Samaan aikaan, hänen mukaansa, Venäjä kykenee kaatamaan sotaan kalustoa ja joukkoja sitä mukaa kun tappioita tulee. Hän nostaa myös esille sodan luonteen eli yllätyksen onnistuminen on vaikeaa tai jopa mahdotonta, mistä syystä sota on hidasta puskemista ja vahvojen asemien valtaamista - eli eteneminen on hidasta, vaikeaa ja tappiot suuria.

Toinen vaihtoehto eli Putinin vallastalähtö puolestaan on hankalaa, koska Putin on rakentanut järjestelmänsä 25 vuoden aikana. Hänen mukaansa Yhdysvalloilla on huono osaaminen "Venäjän sisäpolitiikkaan vaikuttamisessa" ja siten sellaisen yrittäminen tuskin johtaisi haluttuihin tuloksiin. Putin on myös varautunut tähän vaikuttamiseen, mikä vähentää onnistumisen todennäköisyyttä. Hän myös varoittaa että Putin saattaisi "kostaa" nämä yritykset lietsomalla sekasortoa Yhdysvalloissa.

-

JOTEN, jos nuo kaksi vaihtoehtoa ovat "epätodennäköisiä" niin mitä jää jäljelle?

Given those risks, the best approach for Washington is to play the long game and wait for Putin to leave. It’s possible he may step down voluntarily or be pushed out; what is certain is that, at some point, he will die. Only once he is no longer in power can the real work of permanently resolving the war in Ukraine start.

Pitkän pelin pelaaminen ja odottaminen. Putin saattaa astua syrjään vapaaehtoisesti tai pakotettuna, ja vaikka näin ei kävisikään, kukaan ei elä ikuisesti. Artikkelin kirjoittaja on vahvasti sitä mieltä että Ukrainan sodan "pysyvän ratkaisun" hakeminen ei ole mahdollista ennen kuin Putin on pois vallankahvasta.

-

Sinänsä hyvää pohdiskelua, mutta en ole kaikesta samaa mieltä.

En esimerkiksi usko että ryssä kykenee jatkamaan nykymuotoista sotaa loputtomiin. Tarkoitan tätä kaluston osalta, koska varastot tyhjenevät kovaa vauhtia eikä aito uustuotanto riitä paikkaamaan tätä. Samaan aikaan en usko että saisivat ostettua ulkomailta "tarvitsemiaan" sotakoneita. Toisaalta uskon että kykenevät jatkossakin hankkimaan sotilaita, joko vapaaehtoisina tai pakotettuina. Eli täten sodan luonne tulee muuttumaan, mikäli ei ole esim. panssarivaunuja tai IFV-vaunuja samassa määrin kuin aikaisemmin, mutta sota itsessään ei tule loppumaan.

Sodan luonteen muutos erilaiseksi voi antaa Ukrainalle tilaisuuksia edetä, mikäli puntit tasoittuvat kaluston osalta. Toki eteneminen olisi silloinkin hidasta ja tuskaisaa. Eikä ole varmuutta että Ukraina kykenisi tuohon.

Toisekseen artikkeli unohtaa yhden tärkeän vaihtoehdon: Putinin salamurha.

MUOKKAUS: lisäyksenä tähän jälkimmäiseen että tuo näyttää kaikkein ilmeisimmältä ja loogisimmalta "ratkaisulta", jos todetaan tilanne: sota on vahvasti henkilöitynyt Putiniin eikä hänen mielensä tule muuttumaan, maksoi sota mitä tahansa.

JOS tosiaan sodan päätökseen saattaminen ei ole mahdollista niin kauan kuin Putin on vallassa niin silloin Putinin "vallasta poistaminen" niin pian kuin mahdollista on järkevin mahdollinen vaihtoehto.

Länsimaalaisittain moni kavahtaa tällaista koska "emmehän voi alkaa listimään meille ei-mieluisia ihmisiä miten vain" mutta puhuinkin tässä Ukrainasta ja GUR:sta. Heillä on inhorealistisempi näkemys maailmasta, samanlainen kuin vanhalla KGB:llä ja Mossadilla. Oman kansan ja valtion olemassaolo ja tulevaisuus on se mistä tässä puhutaan. Jos sodan lopun hoputtaminen kaipaisi Putinin kuolemaa, niin silloin paras antaa viikatemiehelle kaikki apu mitä kyetään.

Toki "helpommin sanottu kuin tehty", mutta sellaista tämä on. Jos oletetaan että Putin poistuu harvoin bunkkeristaan ja julkiset esiintymiset hoidetaan erilaisten "kaksoisolentojen" avulla, niin listii sitten niitä "kaksosia" yksi toisensa jälkeen kunnes pääsee käsiksi itse pääpiruun.

Muistan GUR:n Budanovin kommentoinen aikaisemmin että olisivat yrittäneet Putinin tappamista jossain vaiheessa, mutta toistaiseksi siinä ei ole onnistuttu. Toivotan onnea uusille yrityksille.

Putinin kuolema ei tietysti takaa ehdottomasti että sota päättyisi siihen ja Ukraina saisi vuoden 1991 rajansa takaisin, mutta selvästikin Putin on merkittävä este. Tämän esteen poistaminen antaa ainakin mahdollisuuden "paremmille vaihtoehdoille". Ei ole varmuutta, on vain tilaisuuksia.

Ydinsekäyttöön tarkoitettuja kh-102:sie ei ole todennä raportoitu. Näitäkin on taatusti ollut jemmassa ja näiden modaus kh-101:seksi lienee helpompaa kuin uuden teko. 50kpl/kk voi siis hyvin pitää paikkansa, samoin 70kpl/kk. Jälkimmäisessä on vain mukana 20kpl/kk 102->101 muutoksia. Sodan alussahan nähtii kh-102:sia inertillä kärjellä. Torjunta tulostenkin valossa kh-102 on melkein käyttökelvoton joten muutos ydinkärjellisestä on nähtävissä täysin järkevänä ratkaisuna turhan ase-arsenaalin siirtona todelliseen hyötykäyttöön.Vähän turhan leveällä pensselillä tuossa maalataan, mutta ei käy kiistäminen etteikö aihe olisi vakava.

Tuosta löytyi hyödyllinen artikkeli numeroita seuraaville (artikkeli julkaistu 25.7.2024 eli kohta 1,5 kuukautta vanha sinänsä): LÄHDE

https://news.liga.net/politics/news/rossiya-ezhemesyachno-proizvodit-okolo-50-raket-x-101

Russia has fewer X-101 missiles, but still produces fifty every month – GUR

Russia currently has about 160 Kh-101 missiles in service, intelligence noted.

Tatyana Lanchukovskaya

LIGA.net News Editor

JULY 25, 12:41

X-101 cruise missile (Photo: occupiers' resource)

Russia produces about 50 units of Kh-101 air-launched cruise missiles every month. This was reported by the press service of the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense in response to a request from LIGA.net .

According to the GUR, at the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia had 440 Kh-101 missiles in its arsenal. In 2023, 460 such missiles were produced in the Russian Federation.

At the same time, Russia currently has about 160 Kh-101 missiles in service and produces 50 units monthly.

When asked about the origin of the components, intelligence noted that 90% of the parts and equipment of Western manufacture for the production of the X-101 missiles are imported to Russia via China.

On July 10, the British newspaper Financial Times, in an article about the missile attack on the Okhmatdet children's hospital, citing a report from the Royal United Services Institute, reported that Russia is now producing almost eight times more Kh-101 missiles than before the full-scale invasion.

According to the publication, in 2021, the Russian Federation produced 56 X-101 missiles, and in 2023 - 420 units.

REFERENCE.

The Kh-101 is a Russian strategic air-to-ground cruise missile using stealth technology. It was first used in combat in 2015 during the Russian intervention in Syria. It is currently being widely used in the war in Ukraine. The missiles are carried by the Tu-95 strategic bomber.

- On July 8, Russians launched a missile attack on the Okhmatdet children's hospital in Kiev. On the same day, the SBU reported that Russia had struck the medical facility with an X-101 cruise missile.

- On July 9, the SBU reported that it had received new confirmation of the type of missile that Russia used to hit the hospital.

- This information was also confirmed by Bellingcat analysts , who analyzed videos from social networks and created a 3D model of the missile.

-

Voi olla että tuo on julkaistu tässä ketjussa aikaisemmin, mutta otetaan varalta talteen ELI Ukrainan GUR:n mukaan ryssän Kh-101 risteilyohjuksen tuotannosta:

- vuonna 2021 valmistivat 56 kpl Kh-101 risteilyohjuksia

- Ukrainan kimppuun hyökkäämisen hetkellä eli 24.2.2022 heillä oli niitä 440 kpl

- vuonna 2023 valmistivat 420 kpl - eli keskiarvoisesti 35 kpl per kuukausi

- tällä hetkellä eli oletan että artikkelin julkaisun aikoihin ryssällä oli niitä 160 kpl käytössään

- he kykenevät valmistamaan "noin 50 kpl per kuukausi" mikä tarkoittaisi keskiarvoisesti "noin 600 kpl" per vuosi

Hyödyllinen datapiste, pitääpä tarkistaa, voisiko sen avulla korjata omaa laskelmaani.

Kh-101 on ryssän selvästi tärkein ja merkittävin strategisen ulottuman ohjusase, tosin kohtuu helposti torjuttavissa myös - ainakin jos verrataan ballistisiin ohjuksiin.

-

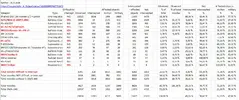

MUOKKAUS: pikainen vertailu keräämieni eri lähteiden eri aikoina kertomille uustuotantomäärille (Kh-101 numerot alleviivattu punaisella):

Katso liite: 103663

35 kpl per kuukausi näyttää loogiselta vuoden 2023 osalta, ainakin jos verrataan aikaisempien arvioiden kanssa: alkuvuonna 2023 määrän kerrottiin olevan noin 30 kpl per kuukausi, toukokuun 2023 loppupuolella 35 kpl per kuukausi ja vähintään elokuun 2023 lopusta alkaen noin 40 kpl per kuukausi.

Helppo uskoa tuollainen tasainen nousu, joskin kuukausien välillä on varmasti jonkin verran vaihtelua. Yleinen trendi lienee silti nouseva.

Vuoden 2024 alkupuolella ja vielä 2.4.2024 määrän kerrottiin olevan sama noin 40 kpl per kuukausi kuin vuoden 2023 viimeisellä kolmanneksellakin (ellei jopa aikaisemmin) MUTTA 1.5.2024 tuli yllättävä väite että määrä olisikin noin 70 kpl per kuukausi. Nyt sitten tuorein minun tiedossa oleva arvio sanoo että 50 kpl per kuukausi.

Tasainen kasvu 40 --> 50 olisi loogisempaa, mutta kenties väliin mahtuu myös muutama tuotteliaampi kuukausi, joten tuo 70 kpl per kuukausi ei välttämättä olisi väärin?

Minun aikaisempi "montako ohjusta ryssällä jäljellä" laskelmani perustui GUR:n Skibitskyn 6.11.2023 kertomiin numeroihin. Se laskelma lipsahti negatiiviseksi Kh-101 osalta, mutta siinä oletettiinkin uustuotannon määräksi 40 kpl per kuukausi (Skibitsky kertoi ko. numeron).

Kuin sattumalta myös silloin Kh-101 risteilyohjusten jäljelläolevaksi määräksi kerrottiin 160 kpl eli sama kuin nyt 25.7.2024.

Mikä tarkoittaisi sitä että ryssä olisi kyennyt valmistamaan tuolla aikavälillä samansuuruisen määrän näitä ohjuksia kuin mitä ovat käyttäneet.

Ukrainan "torjuntailmoitusten" perusteella voidaan laskea että aikavälillä 6.11.2023 - 25.7.2024 ryssä olisi käyttänyt vähintään 595 kpl Kh-101 risteilyohjuksia. Tuo aikaväli on 262 päivää eli karkeasti ottaen 8,73 kuukautta. Mistä voidaan laskea keskiarvoinen kuukausituotanto tälle aikavälille: 68,13 kpl per kuukausi.

MUTTA tämä keskiarvo asettaa outoon valoon tuoreen väitteen että uustuotannon määrä olisi vain 50 kpl per kuukausi. Tuntuisi loogisemmalta että se olisi 70 kpl per kuukausi, ellei jopa vähän sen yli. Toki tuotannon vaikeudet voivat aiheuttaa suuriakin heilahduksia eri kuukausien välille, joita sitten pidemmän aikavälin keskiarvot tasaavat (ja sekoittavat).

HUOM: virhe voi myös johtua muista syistä, esim. torjuntailmoitukset eivät välttämättä kerro 100% tarkkuudella sitä, mitä risteilyohjuksia on torjuttu. Tätä on mahdotonta kompensoida. Lisäksi torjutuksia väitetty Kh-101 voi olla esim. valemaali tai muu vastaava. Ukraina ei ole muistaakseni koskaan julkaissut "korjauksia" aikaisemmille torjuntailmoituksille eli kun sellainen on yhden kerran annettu, se tieto on ja pysyy.

Olen vähän hämmentynyt näiden numeroiden kanssa: vielä 2.4.2024 Skibitsky kertoi uustuotannon määräksi 40 kpl per kuukausi. Olisi loogista että määrä kasvaisi tasaisesti, kuten se kasvoi vuonna 2023. Joten olisi loogista että kesällä 2024 se olisi 45 tai 50 kpl per kuukausi.

Mutta tuo ei selitä, miten ryssä kykeni käyttämään noin 600 kpl näitä vajaan 9 kuukauden aikana ja sen jälkeenkin varastoissa oleva määrä olisi sama 160 kpl kuin 6.11.2023.

JOS uustuotanto olisi todella kasvanut tasaisesti 40 --> 50 niin mistä ovat peräisin noin 200 kpl risteilyohjuksia, jotka he ovat käyttäneet? Muuten tosiaan laskelma menee negatiiviseksi, kuten minulla kävi keväällä 2024. Eikä yksittäinen "parempi kuukausi" selitä tällaista määrää.

Ydinsekäyttöön tarkoitettuja kh-102:sie ei ole todennä raportoitu. Näitäkin on taatusti ollut jemmassa ja näiden modaus kh-101:seksi lienee helpompaa kuin uuden teko. 50kpl/kk voi siis hyvin pitää paikkansa, samoin 70kpl/kk. Jälkimmäisessä on vain mukana 20kpl/kk 102->101 muutoksia. Sodan alussahan nähtii kh-102:sia inertillä kärjellä. Torjunta tulostenkin valossa kh-102 on melkein käyttökelvoton joten muutos ydinkärjellisestä on nähtävissä täysin järkevänä ratkaisuna turhan ase-arsenaalin siirtona todelliseen hyötykäyttöön.

Näille ohjuksille löytyi toinenkin potenttiaalinen lähde. Pienellä kaivamisella löytyi uutinen että kh-55 ohjuksia olisi myyty vuosituhannen alussa Iraniin ja KiinaanTuossa voi olla perää, koska suhtaudun epäileväisesti siihen että aito uustuotanto hyppäisi yhtäkkiä 40 --> 70 kpl per kuukausi.

Olisi loogisempaa että ydinasekäyttöön varatuista risteilyohjuksista "vapautettaisiin" esimerkiksi 200 kpl, jotka sitten käytettäisiin pois Ukrainassa (jonkinlaisten muutostöiden jälkeen tietysti).

Yleinen aidon uustuotannon nousu olisi myös looginen selitys sille, miksi tuollainen "vapauttaminen" onnistuisi: tiedetään että vuonna 2024 kyettäneen valmistamaan noin 600 kpl Kh-101 risteilyohjuksia, joten jokin osa tästä voidaan jyvittää Kh-102 tuotannolle. Tällöin varastoista vapautuu vastaava määrä Kh-102 risteilyohjuksia Ukrainassa käytettäväksi. Eikä sen uustuotannon täytyne tapahtua heti vaan voidaan valmistaa esim. 5-10 kpl Kh-102 ohjuksia per kuukausi, jolloin loput voivat olla Kh-101 ohjuksia. Tällöin tuo pois käytetty määrä saadaan takaisin kahdessa vuodessa.

Toki on myös mahdollista että heillä tuli tietyn määrän osalta ajankohtaiseksi "määräaikaishuolto" ja siinä vaiheessa päätettiin että sen lisäksi ohjukset muutetaankin Ukrainassa käytettäviksi ja korvataan uustuotannosta valmistuvilla. Olen taipuvaisempi uskomaan että ryssä teki muutokset jotta saivat suuremman määrän ohjuksia Ukrainaa vastaan käytettäväksi eikä se johdu siitä että "ohjuksien parasta-ennen-päiväys alkoi lähestymään".

Millainen määrä voisi olla kyseessä? Spekuloidaan Ukrainan eri aikoina julkisuuteen kertomilla Kh-101 uustuotannon määrillä:

11.2023 = 40

12.2023 = 40

1.2024 = 40

2.2024 = 40

3.2024 = 40

4.2024 = 40

5.2024 = 50

6.2024 = 50

7.2024 = 50

Näiden summa on 390 kpl.

Samalla aikavälillä Ukrainan torjuntailmoitusten perusteella ryssän sanotaan käyttäneen ainakin 595 kpl Kh-101 risteilyohjuksia.

Näiden erotus on 205 kpl, tosin tuo yllä oleva kuukausittaisen uustuotannon lista on ihan vain minun mielikuvituksen tuotetta. Tarkkoja lukuja ei tiedetä, kunhan vain suhteutin tuon siihen mitä Ukraina on ilmoittanut eri aikoina. Siellä voi helposti olla suuriakin vaihteluita todellisuudessa ja jonain kuukautena määrä voi olla vaikka 45 kpl - tai jotain muuta.

Ukrainan torjuntailmoitukset eivät myöskään sisällä 100% kaikkia ryssän ohjuslaukaisuja ja toisaalta niissä voi myös olla virheitä eli on tunnistettu jotain väärin tms.

Minun on silti helpompi selittää itselleni nämä numerot siten että oikea uustuotanto on tällä hetkellä noin 50 kpl per kuukausi ja talven / kevään 2024 suurempi käytettyjen ohjusten määrä selittyy tuollaisella varastoitujen ohjusten "vapauttamisella". Tai eihän sitä tiedä, ehkä heiltä löytyi jostain vanha, aikaisemmin tuntematon varasto Kh-55 risteilyohjuksia, jotka sitten kunnostettiin ja käytettiin pois?

Joka tapauksessa hyvä pitää silmällä, miten Ukraina kommentoi jatkossa Kh-101 uustuotantoa eli pysyykö se "noin 50 kpl" per kuukausi tasolla vai onko jotain muuta.