The Swiss "4th Gen Sniper" training technique is excellent, and I have seen some very good videos of troops training on military, town, and canton ranges.

This is the exact concept -- training regular guys to shoot past the basic 300 Meter requirement with an issue Sturmgewehr with a simple and robust scope with quality glass. Swiss GP-90 5.56 is already of known, good quality, and standard 7.62 is not bad, either.

Not everyone can or SHOULD do it, but it is a very powerful capability if two, three, or more guys in a unit can do it with consistency, day, night, in forest, up and down hills, and across valleys.

This is a sample of what he means:

This is the concept (stolen from another site):

===== ===== =====

"This is a description by "Bold," a forum member from Germany, of a Swiss mil program, "Sniping 4th Generation" (S4G). It's an interesting read; I hope you find it so.

The Swiss have a very interesting designated marksman concept called "sniping 4th generation" (abbr. S4G).

In a single day of training, S4G enables an ordinary shooter to hit a man-sized target at 600 metres with the Swiss service rifle and a decades-old fixed 4x-scope - not with every shot, but with a very short target exposure time required.

The math behind S4G is centered around a practical accuracy of 1 per mill - "practical" meaning the combination of rifle, ammo, optics, shooter, and "per mill" meaning a deviation of not more than one metre at 1000 metres, or 10 centimetres at 100 metres. That amounts to round about 3.4 MOA, which is not too difficult to achieve.

(If anyone is interested, I can write a short overview of S4G).

Why am I even mentioning this?

In the S4G courses I personally took and in those friends of mine did, it was quite evident that any shooter who has the basics down can utilize the S4G concept almost from the very start to make hits. Many shooters in the courses had never shot past 100 meters before (!) and achieved first-try hits.

So, what I´m saying is that one may not be sacrificing the ability to hit at longer ranges when training at shorter ones at all, or at least not to the extent suspected.

As long as we are talking about distances where the relevant variables can be handled with a scientific wild-ass guess and not "real" spotter´s work, it is still all about the basics.

And those distances are, depending on the weapon system, the 500-700 meters you mentioned above.

Having said all that, I think in a civilian rifle work context there are only two ranges:

A) The range where an attacker can obviously and intuitively pose a threat almost regardless of his weapons, and his intent can be identified from things other than him shooting at you.

B) The range where you have either a rifle fight or no fight at all.

Training should be focussed on the first range for the simple reason that this is the variant one is much more likely to encounter (with clearly identifiable intent being the key factor) - let´s say 50 meters and in (and 50 meters is already pretty far in this context, isn´t it?).

As long as utmost accuracy is regularly trained for at shorter ranges, you are quite likely good to go at longer distances.

There are differences between an eyeball at 20 meters, a head at 150 and a man at 500, but they are not so great as to make regular and intensive training at long range a necessity.

As for the optics:

In a civilian context, the big bonus of magnification shifts from finding targets to deciding whether they need shooting (yet).

Magnified optics still make a lot of sense there IMO.

Now, about the S4G concept and course:

S4G is intended to enable a regular shooter to hit man-sized targets as fast as possible at distances of around 600 meters, depending on the weapon used.

The concept assumes that in many situations, it will take too long or be otherwise impossible or at least very difficult to get an accurate estimation of distance. Thus a shooter will not be able to adjust his scope accordingly (which would also take time) or use the correct holdover marking, if his reticle offers any.

The goal of the concept is therefore to provide the shooter with the means to hit a man-sized target in a short amount of time without the need to know the exact distance and without making any adjustments, freeing him of unnecessary choices and removing the need to fiddle with the weapon system under stress.

Naturally, this means that not every shot will be a hit. But every shot will have an acceptable chance to become a hit.

For the designated marksman, the Swiss regard quick hits with a few more rounds expended as superior to a perfect single round hit that took the better part of a minute or more to set up or a shot - because the latter method might see a lot of shots that are never taken as the target has disappeared in the meantime.

With the goal in mind, let´s take a look at the course:

The course starts in the KD-Box ("Kurzdistanz-Box", i.e. short distance range) at 25 meters.

First we are taught a simple and universal method of zeroing a scope with unreadable or no markings.

We fire a 3 shot group at 25 meters (prone with a daypack as a rifle rest) and adjust windage by 10 clicks. Then, we fire 3 more shots, measure the distance between the centers of the two groups and divide it by 10 (any number will do, but it needs to be large enough to compensate for small shooting errors and other deviation factors – so adjusting by a single click is out, but you could just as well use 20 clicks and divide by 20, for example). Now we know the adjustment one click will give us at 25 meters.

We repeat the process for elevation and now have the numbers to adjust our formerly unknown scope to point of aim = point of impact at 25 meters.

Depending on the rifle and scope, this will give us a zero of 25 / 300(ish) – the exact distance for the second intersection is not too important.

The next step is how to estimate distance.

When we look at a target with our Mk1 eyeball and can see any kind of detail, that is a close target.

Details would be stuff like gender, hair color, hair style, general type of clothing (e.g. wearing a jacket or not), other equipment (e.g. backpack, rifle) etc..

With a close target, we will aim at the hip, since generally the target will be within ~300 meters and our bullet will impact above the line of sight and thus somewhere on the torso.

When we cannot make out any of those details and are just able to see a person, we have a far target.

With a far target, we aim at the neck/head, since our bullet will impact below the line of sight – again, somewhere on the torso.

The beauty of this is that we do not have to worry about the grey area between close and far targets.

As we approach the end of close distance, our point of impact moves closer to our point of aim – we will still hit the hip or groin area.

If we go to the far target hold too early, the bullet will not hit below our line of sight, but rather high on the torso or in the shoulder/head area – no big loss, is it?

Basically, all we are doing is taking the Battlesight Zero concept and adding a single step of complexity: instead of always aiming at the center of a given target, we aim at the lower end of the target at close range and the higher end at long range.

Next comes correction for wind.

For a close target, we do not correct for wind at all.

For a far target, we correct half the target´s width for weak wind. Weak wind is wind that can be felt on exposed skin, but will not significantly sway trees or make clothing flap about.

According to the definition of weak wind, we now know what strong wind would be – anything noticeably stronger than weak wind.

In strong wind, we hold a full target´s width into the wind, i.e. we imagine a "virtual twin" right beside our target and hold at its neck/head area.

The shooting itself consists of two parts:

The first shot is a carefully aimed single shot. If it hits and produces perceptible results, we can stop.

If it does not produce results, be it from a miss or a bad hit, we change to what the Swiss call "rasches Einzelfeuer" – rapid semi-auto.

Depending on our shooting position and distance, we shoot five shots at a steady rhythm of 1 to 2 rounds per second.

We do not try to see bullet impact, we do not change our point of aim.

The thinking behind that is this:

If we missed our first shot (or had a bad hit), something went wrong. We could have misjudged distance or wind. Maybe we jerked the trigger or maybe it was something else. We do not know and we do not have the time to find out.

What we try to achieve with our rapid follow-up is to increase our deviation just to the point where one of the shots we fire will cancel out our earlier mistake, but not so far as to miss the target completely.

Once you have shot a few bouts of rapid semi-auto with tracer ammo, you get a pretty good feeling how fast you can go / need to go.

Again, the trick is to not be too accurate (!) - if the miss was a result of a misjudgement, we will just put more rounds off target if we shoot to accurately.

The Swiss army is taught to shoot this way (one aimed shot with eventual rapid-fire follow-up) at all distances.

Depending on target exposure time, distance or movement, we might skip the carefully aimed shot and start with rapid semi-auto fire – our call.

Putting it all together, let´s say we perceive a possible target.

As we establish our shooting position, we go through the very short check list.

Do we see details? - No. FAR target, neck/head hold.

Wind? - Just a touch on the face from the right side: WEAK, HALF a target´s width into the wind.

At the time we are content with our shooting position, we already know that we need to aim just above the right shoulder of the target – the process took us mere seconds (and can be practiced any time you go out for a walk...).

And that´s about it...with a combination of stuff we most likely knew already, we can now produce hits on targets at 500-600 meters with any type of reticle and without any adjustments on our scope.

Mind you, all of the shooting we did up to now was in the KD-Box at 25 meters...

After a short lunch break, we head off to the "real" range and start out at 600 meters.

If we shoot exactly like we did at 25 meters in the morning, the hits will be there.

After some time, when everybody has gotten the hang of it, we move closer to the targets and shoot from unconventional positions - just to give people a feeling for what they can get away with and still make hits.

After the 600 meter distance, targets at 200 and in feel like shooting at barnsides.

We get to walk our aiming point up and down the target until we miss low or high. This is to show us that at closer ranges, we still make hits if we forget about our low aiming point for whatever reason and just hold center mass.

Moving closer, we see that we can still hit despite the fixed x4 optic at closer ranges if we have to.

The shooting part of the day ends with reaching the targets and one of the instructors having us turn around and look at the house at 600 meters where we shot from after lunch.

"I made hits from there?" is written on the face of more than one student

Finally, some random observations and bits of info:

- Most student groups achieve hit rates of 80% and more for a "complete attack cycle" of one carefully aimed shot with rapid-fire follow-up.

- With the practical accuracy of 1 per mill I mentioned in my other post above, a shooter will hit a box of 60x60 centimeters (23,6 inches approx.) at 600 meters. Looking at those numbers, it suddenly seems not too hard to get one or a few hits on a man-sized target at that distance.

- The infantry in the German armed forces is currently experimenting with S4G adapted to the HK G36 rifle.

Although the G36´s integral scope was designed with holdover markings out to 800 meters, using only the "main" reticle and the S4G concept, results have been significantly better.

S4G will likely become a part of the new shooting curriculum that is being implemented lately.

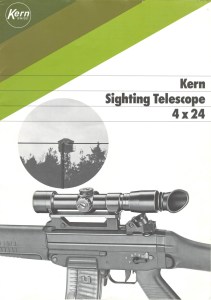

- The Kern 4x24 scope the Swiss use on their rifles is a stroke of genius IMO.

It features a hollow aiming post that makes it very easy to observe through the scope while still providing a good reticle and the ability to spot rifle cant.

A tritium-based reticle illumination can be cut off with the turn of a knob.

While the mount is proprietary to the Swiss service rifles, it can be mounted in less than 5 seconds and taken off in 3 while retaining its zero (!). To build confidence in the scope, instructors had us zero our guns at 25 meters, then take off the scope and pass it to our right neighbour. For most people, mounting the scope they got from the shooter to ther left had no noticeable effect on their hits.

The mount is made of the same metal as the rifle itself to reduce tension when the gun gets hot.

Not too shabby for a scope designed in the 1960s..."

threadreaderapp.com

threadreaderapp.com

"Unpacking" the tactics of the Wagnerites north of Soledar through the eyes of a very competent Ukrainian officer, one of the participants in the defense.

"Unpacking" the tactics of the Wagnerites north of Soledar through the eyes of a very competent Ukrainian officer, one of the participants in the defense. At first, the first group, usually of 8 people, is put forward to the finish line. The whole group is maximally loaded with BC (Perpetuan mukaan BC = ammo mutta oletan että voisi tarkoittaa luotien ja lippaiden lisäksi käsikranaatteja yms. Kirjoitan silti jatkossa tämän jälkeen "BC = ammo"), each has a "Bumblebee" flamethrower. Their task is to get to the point and get a foothold. They are almost suicidal. Their BC (BC = ammo) in case of failure is intended for the following groups.

At first, the first group, usually of 8 people, is put forward to the finish line. The whole group is maximally loaded with BC (Perpetuan mukaan BC = ammo mutta oletan että voisi tarkoittaa luotien ja lippaiden lisäksi käsikranaatteja yms. Kirjoitan silti jatkossa tämän jälkeen "BC = ammo"), each has a "Bumblebee" flamethrower. Their task is to get to the point and get a foothold. They are almost suicidal. Their BC (BC = ammo) in case of failure is intended for the following groups. Have light "armor" at a distance of short jumps. As soon as the drone operators notice the movement of the occupiers towards the positions, they inform the "armor". But quickly suppresses the attack of the "Wagnerians" even with machine guns. If there is no "armor", then it is difficult to restrain such assault actions.

Have light "armor" at a distance of short jumps. As soon as the drone operators notice the movement of the occupiers towards the positions, they inform the "armor". But quickly suppresses the attack of the "Wagnerians" even with machine guns. If there is no "armor", then it is difficult to restrain such assault actions.