In late 2021, operators of the European Space Agency's (ESA) Swarm constellation noticed something worrying: The satellites, which measure the magnetic field around Earth, started sinking toward the atmosphere at an unusually fast rate — up to 10 times faster than before. The change coincided with the onset of the new solar cycle, and experts think it might be the beginning of some difficult years for spacecraft orbiting our planet.

"In the last five, six years, the satellites were sinking about two and a half kilometers [1.5 miles] a year," Anja Stromme, ESA's Swarm mission manager, told Space.com. "But since December last year, they have been virtually diving. The sink rate between December and April has been 20 kilometers [12 miles] per year."

Satellites orbiting close to

Earth always face the drag of the residual

atmosphere, which gradually slows the spacecraft and eventually makes them fall back to the planet. (They usually don't survive this so-called re-entry and burn up in the atmosphere.) This atmospheric drag forces the

International Space Station's controllers to perform regular

"reboost" maneuvers to maintain the station's orbit of 250 miles (400 km) above Earth.

This drag also helps clean up the near-Earth environment from space junk. Scientists know that the intensity of this drag depends on solar activity — the amount of

solar wind spewed by the

sun, which varies depending on the

11-year solar cycle. The last cycle, which officially ended in December 2019, was rather sleepy, with a below-average number of monthly

sunspots and a prolonged minimum of barely any activity. But since last fall, the

star has been waking up, spewing more and more solar wind and generating sunspots,

solar flares and

coronal mass ejections at a growing rate. And the Earth's upper atmosphere has felt the effects.

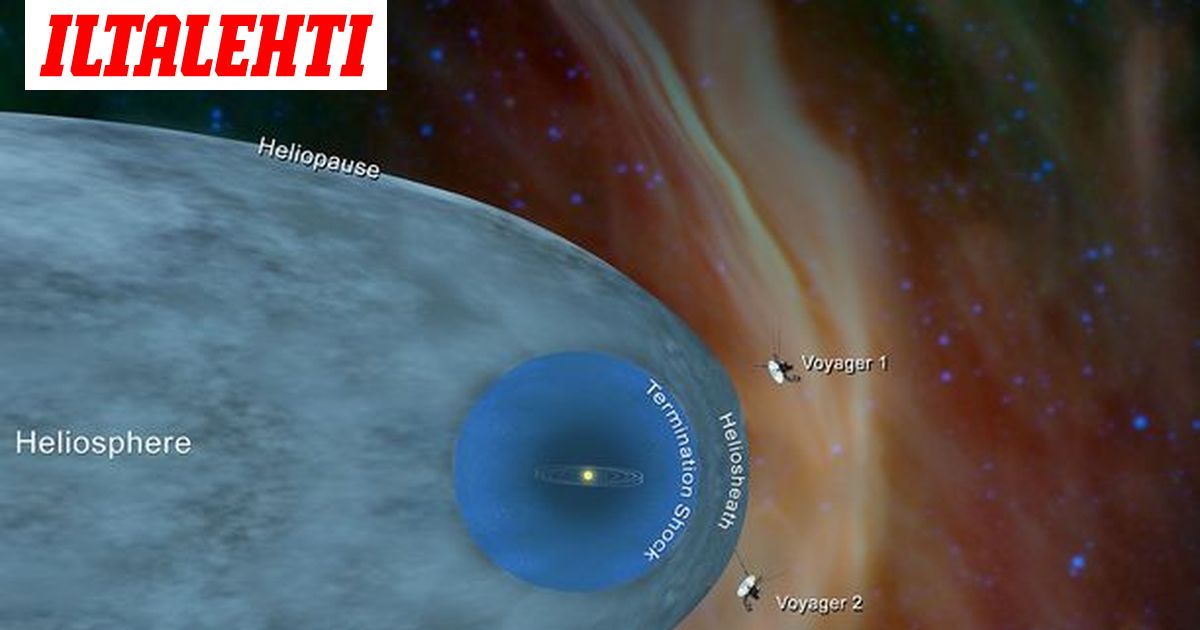

? Vastaus on ei. Voyagerilla ei ole mitään muuta virkaa kuin kulkea matkansa ja toivottavasti päätyen jossain vaiheessa jonkun toisen käsiin. Me tiedämme omasta kokemuksesta kuinka nämä "Interstellar Visitors" on vaikea havaita, ja koko tilaisuus voi mennä ohi. Ja totuus on että atomipatterissa ei riitä virtaa niin pitkiksi ajoiksi, joten sen havaitseminen jonkun toisessa aurinkokunnassa on sattumakauppaa.

? Vastaus on ei. Voyagerilla ei ole mitään muuta virkaa kuin kulkea matkansa ja toivottavasti päätyen jossain vaiheessa jonkun toisen käsiin. Me tiedämme omasta kokemuksesta kuinka nämä "Interstellar Visitors" on vaikea havaita, ja koko tilaisuus voi mennä ohi. Ja totuus on että atomipatterissa ei riitä virtaa niin pitkiksi ajoiksi, joten sen havaitseminen jonkun toisessa aurinkokunnassa on sattumakauppaa.