Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Informaatiosodankäynti, propaganda ja kulttuurivaikuttaminen - Turvallisuuden ulottuvuus

- Viestiketjun aloittaja LasUps

- Aloitus PVM

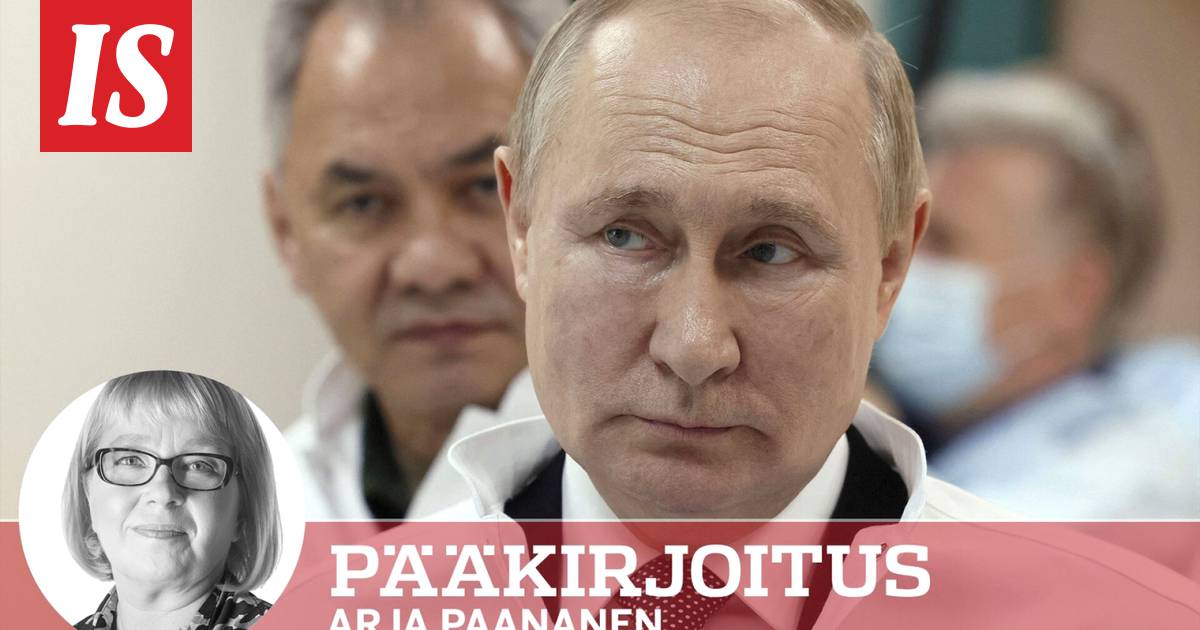

Arja Paanasen artikkeli putinisteista ja muista niille myötämielisistä hyödyllisistä idiooteista, vahva lukusuositus niille, ketkä eivät aiheeseen törmää esim. twitterin puolella:

www.is.fi

www.is.fi

Arja Paananen

21:15

Satuitteko muuten huomaamaan, että suomalaiset suuttuivat oikein joukolla, kun tasavallan presidentti Sauli Niinistö perusteli Suomen Nato-hakemusta Venäjän omilla teoilla? Siis se hetki, kun Niinistö lausui kuuluisat sanansa: ”Te aiheutitte tämän, katsokaa peiliin.”

Ei ihme, jos ette huomanneet – sillä niinhän Suomessa ei tosiasiassa tapahtunut.

Suuttumuksen sijaan Niinistö keräsi laajasti kehuja siitä, kuinka hän tiivisti suomalaisten nopeasti muuttuneen Nato-kannan syyt yhteen lauseeseen.

Venäjän mediassa ilmestyi kuitenkin uutisia, joiden mukaan suomalaiset pöyristyivät Niinistön peili-kommentista. Esimerkiksi valtiollisen Ria Novosti -uutistoimiston artikkeliin oli otettu lainauksia neljältä väitetyltä suomalaiselta Twitter-kommentoijalta ilman, että juttuun oli liitetty linkkejä alkuperäisiin kirjoituksiin.

Viesteissä Niinistöä arvostellaan muun muassa siitä, että syytös on liian rankka Venäjää kohtaan. Kun viestit kääntää suomeksi ja yrittää etsiä niitä Twitteristä, tehtävä osoittautuu haasteelliseksi. Liekö niitä koskaan ollutkaan vai oliko julkaisija joku kuvaton nollan seuraajan bottitili?

Edellä kuvattu episodi on pieni esimerkki siitä, miltä Suomea koskeva uutisointi näyttää nyt Venäjän mediassa. Totuuden kanssa sillä on hyvin vähän tekemistä.

Venäläisten mahdollisuus saada oikeaa tietoa supistui tällä viikolla entisestään, kun Venäjä esti pääsyn myös Helsingin Sanomien verkkosivuille. Ilta-Sanomien sivut blokattiin Venäjällä ensimmäisenä suomalaismediana jo Ukrainan uuden sodan alkuvaiheessa.

Syyksi estoille on kerrottu HS:n ja IS:n julkaisemat venäjänkieliset artikkelit. VPN-yhteydellä molempien lehtien sivuille pääsee vielä, mutta läheskään kaikki venäläiset eivät uskalla tai viitsi ottaa palvelua käyttöön.

Venäjän mediassa on noussut Ukrainan sodan aikana esiin myös useita innokkaita suomalaisia ”asiantuntijoita” ja ”toimittajia”. Yhteistä heille on, että he ovat suurelle suomalaiselle yleisölle joko täysin tuntemattomia tai heidät tiedetään jo entuudestaan Vladimir Putinin politiikan ihailijoiksi.

Näitä ”arvostettuja suomalaisia yhteiskunnallisia vaikuttajia” Venäjän media haastattelee nyt mielellään. Suomalaispropagandisteilla näyttää olevan yksi pääviesti: Suomea viedään vastoin kansan tahtoa Natoon.

Propagandistit toistavat myös väitteitä, joiden mukaan Suomen media pelottelee perusteettomasti Venäjän uhalla, suomalaisilta on viety kokonaan sananvapaus ja Natoa koskevat mielipidetiedustelut ovat vääristeltyjä. Näin Yhdysvallat pääsee väitetysti vetämään Suomen mukaan omiin ”hyökkäysvalmisteluihinsa” Venäjää vastaan.

Monet venäläiset ovat tottuneet luottamaan suomalaisten sanoihin ja tekoihin – ja juuri siksi suomalaiset propagandistit ovat nyt erityisen kysyttyjä Venäjällä luomaan uskottavuuden illuusiota.

Mainittakoon heistä tässä nimeltä vain vanha tuttu Johan Bäckman, jonka mielikuvitus näyttää olevan ehtymätön. Bäckmanin sanomiset eivät sinänsä ansaitse julkisuutta, mutta kerrottakoon esimerkinomaisesti hänen tuorein Venäjällä uutisoitu ”teoriansa”, jonka mukaan Britannia saattaisi pudottaa tarkoituksella alas suomalaisen tai ruotsalaisen matkustajakoneen ja miehittää sen jälkeen Ahvenanmaan.

On ymmärrettävää, että kukaan Suomen johtava poliitikko, tutkija tai diplomaatti ei ole erityisen halukas antamaan haastatteluja Venäjän medialle. Siinä joutuu aina joka tapauksessa jollain tavalla hyväksikäytetyksi tai vääristellyksi.

Tämä johtaa kuitenkin toiseen ongelmaan. Venäjän median koko Suomea käsittelevä infotila jää nyt erilaisten suomalaisten tekoasiantuntijoiden vapaaksi temmellyskentäksi.

Pääkirjoitus: Putinin innokkaat Suomi-apurit – näin Venäjä hyödyntää nyt suomalaisia propagandisteja

Venäjän median koko Suomea käsittelevä infotila on täyttymässä suomalaisilla tekoasiantuntijoilla, jotka ovat halukkaita tukemaan Vladimir Putinin politiikkaa, Arja Paananen kirjoittaa.

Pääkirjoitus: Putinin innokkaat Suomi-apurit – näin Venäjä hyödyntää nyt suomalaisia propagandisteja

Venäjän median koko Suomea käsittelevä infotila on täyttymässä suomalaisilla tekoasiantuntijoilla, jotka ovat halukkaita tukemaan Vladimir Putinin politiikkaa, Arja Paananen kirjoittaa.Arja Paananen

21:15

Satuitteko muuten huomaamaan, että suomalaiset suuttuivat oikein joukolla, kun tasavallan presidentti Sauli Niinistö perusteli Suomen Nato-hakemusta Venäjän omilla teoilla? Siis se hetki, kun Niinistö lausui kuuluisat sanansa: ”Te aiheutitte tämän, katsokaa peiliin.”

Ei ihme, jos ette huomanneet – sillä niinhän Suomessa ei tosiasiassa tapahtunut.

Suuttumuksen sijaan Niinistö keräsi laajasti kehuja siitä, kuinka hän tiivisti suomalaisten nopeasti muuttuneen Nato-kannan syyt yhteen lauseeseen.

Venäjän mediassa ilmestyi kuitenkin uutisia, joiden mukaan suomalaiset pöyristyivät Niinistön peili-kommentista. Esimerkiksi valtiollisen Ria Novosti -uutistoimiston artikkeliin oli otettu lainauksia neljältä väitetyltä suomalaiselta Twitter-kommentoijalta ilman, että juttuun oli liitetty linkkejä alkuperäisiin kirjoituksiin.

Viesteissä Niinistöä arvostellaan muun muassa siitä, että syytös on liian rankka Venäjää kohtaan. Kun viestit kääntää suomeksi ja yrittää etsiä niitä Twitteristä, tehtävä osoittautuu haasteelliseksi. Liekö niitä koskaan ollutkaan vai oliko julkaisija joku kuvaton nollan seuraajan bottitili?

Edellä kuvattu episodi on pieni esimerkki siitä, miltä Suomea koskeva uutisointi näyttää nyt Venäjän mediassa. Totuuden kanssa sillä on hyvin vähän tekemistä.

Venäläisten mahdollisuus saada oikeaa tietoa supistui tällä viikolla entisestään, kun Venäjä esti pääsyn myös Helsingin Sanomien verkkosivuille. Ilta-Sanomien sivut blokattiin Venäjällä ensimmäisenä suomalaismediana jo Ukrainan uuden sodan alkuvaiheessa.

Syyksi estoille on kerrottu HS:n ja IS:n julkaisemat venäjänkieliset artikkelit. VPN-yhteydellä molempien lehtien sivuille pääsee vielä, mutta läheskään kaikki venäläiset eivät uskalla tai viitsi ottaa palvelua käyttöön.

Venäjän mediassa on noussut Ukrainan sodan aikana esiin myös useita innokkaita suomalaisia ”asiantuntijoita” ja ”toimittajia”. Yhteistä heille on, että he ovat suurelle suomalaiselle yleisölle joko täysin tuntemattomia tai heidät tiedetään jo entuudestaan Vladimir Putinin politiikan ihailijoiksi.

Näitä ”arvostettuja suomalaisia yhteiskunnallisia vaikuttajia” Venäjän media haastattelee nyt mielellään. Suomalaispropagandisteilla näyttää olevan yksi pääviesti: Suomea viedään vastoin kansan tahtoa Natoon.

Propagandistit toistavat myös väitteitä, joiden mukaan Suomen media pelottelee perusteettomasti Venäjän uhalla, suomalaisilta on viety kokonaan sananvapaus ja Natoa koskevat mielipidetiedustelut ovat vääristeltyjä. Näin Yhdysvallat pääsee väitetysti vetämään Suomen mukaan omiin ”hyökkäysvalmisteluihinsa” Venäjää vastaan.

Monet venäläiset ovat tottuneet luottamaan suomalaisten sanoihin ja tekoihin – ja juuri siksi suomalaiset propagandistit ovat nyt erityisen kysyttyjä Venäjällä luomaan uskottavuuden illuusiota.

Mainittakoon heistä tässä nimeltä vain vanha tuttu Johan Bäckman, jonka mielikuvitus näyttää olevan ehtymätön. Bäckmanin sanomiset eivät sinänsä ansaitse julkisuutta, mutta kerrottakoon esimerkinomaisesti hänen tuorein Venäjällä uutisoitu ”teoriansa”, jonka mukaan Britannia saattaisi pudottaa tarkoituksella alas suomalaisen tai ruotsalaisen matkustajakoneen ja miehittää sen jälkeen Ahvenanmaan.

On ymmärrettävää, että kukaan Suomen johtava poliitikko, tutkija tai diplomaatti ei ole erityisen halukas antamaan haastatteluja Venäjän medialle. Siinä joutuu aina joka tapauksessa jollain tavalla hyväksikäytetyksi tai vääristellyksi.

Tämä johtaa kuitenkin toiseen ongelmaan. Venäjän median koko Suomea käsittelevä infotila jää nyt erilaisten suomalaisten tekoasiantuntijoiden vapaaksi temmellyskentäksi.

Laitoin taas pitkästä aikaa vähän rahaa ukrainan keskuspankin tilille lahjoituksena. Etsiessäni netistä ko. sivua googlehaku antoi ensin parin sivun verran MV-lehden kirjoituksia siitä miten ukraina on paha. Viimeksi, noin kk sitten ei vielä tälläistä näkynyt. Infosota on alkanut selvästi vahvistumaan.

rty19

Greatest Leader

HS: 90 prosenttia Otto-automaateista kyykkäsi – ”Mielenkiinnolla odotan, mikä tässä oli taustalla”

Automaatit jouduttiin palauttamaan manuaalisesti etäyhteyksien avulla.

Laitan tänne, esimerkkinä

www.theregister.com

www.theregister.com

Japan has updated its penal code to make insulting people online a crime punishable by a year of incarceration.

An amendment [PDF] that passed the House of Councillors (Japan's upper legislative chamber) on Monday spells out that insults designed to hurt the reader can now attract increased punishments.

Supporters of the amended law cite the death of 22-year-old wrestler and reality TV personality Hana Kimura as a reason it was needed. On the day she passed away, Kimura shared images of self-harm and hateful comments she'd received on social media. Her death was later ruled a suicide.

Three men were investigated for their role in Kimura's death. One was fined a small sum, and another paid around $12,000 of damages after a civil suit brought by Kimura's family.

Before the amendment, Japanese law allowed for 30 days inside for insults, or fines up to ¥10,000 ($75). The law now permits up to a year inside and imposes a ceiling of ¥300,000 ($2,200) on fines.

Japan increases jail time for online insults to one year

Law will be reviewed after three years amid debate on free speech vs civility

Sixteen years ago, British mathematician Clive Humby came up with the aphorism "data is the new oil".

Rather than something that needed to be managed, Humby argued data could be prospected, mined, refined, productized, and on-sold – essentially the core activities of 21st century IT. Yet while data has become a source of endless bounty, its intrinsic value remains difficult to define.

That's a problem, because what cannot be valued cannot be insured. A decade ago, insurers started looking at offering policies to insure data against loss. But in the absence of any methodology for valuing that data, the idea quickly landed in the "too hard" basket.

Or, more accurately, landed on the to-do lists of IT departments who valued data by asking the business how long they could live without it. That calculus led to determining objectives for recovery point and recovery time, then paying what it took to build (and regularly test) backups that achieve those deadlines to restore access to data and the systems that wield it.

That strategy, while sound, did not anticipate ransomware.

Cyber criminals have learned how to exploit every available attack surface to make firms' hard-to-value-but-oh-so-vital data impossible to use. Ransomware transforms data in situ into cryptographic noise – the equivalent of a kidnapper displaying their hostage, while laughing at the powerlessness of the authorities.

Businesses now face not just data loss but data theft. The data is not only gone – it's been "liberated" by a threat actor who chooses to share exactly the parts of that data most damaging to your business, your customers, and your brand.

Do you still have a business? If so, how many lawsuits have been launched by clients who have themselves been damaged by your inability to keep private data private? Who will want to do business with you in the future? And can you ever again trust any of your systems – or your staff?

Sony barely survived the reputational damage of the serious attack it endured in 2014 – and it's not clear that any other business would do significantly better in similar circumstances.

If you don't store valuable data, ransomware is impotent

Start by pondering if customers could store their own info and provide access

(140 diploa, joista puolet karkotettiin sai aikaan mielleyhtymän.

Jutun otsikko "Is Zero Hedge a Russian Trojan Horse?

The father of the founder of the conspiratorial site filed a criminal complaint against me in Bulgaria. Then things got weird.")

The New York Times describes Pegasus as "a 'zero-click' hacking tool that can remotely extract everything from a target's mobile phone [and] turn the mobile phone into a tracking and recording device." But they also report that the tool's "notorious" maker, NSO Group, was visited "numerous times" in recent months by a executives from American military contractor L3Harris — makes of the cellphone-tracking Stingray tool — who'd wanted to negotiate a purchase of the company.

Their first problem? The U.S. government had blacklisted NSO Group in November, saying Pegasus had been used to compromise phones of political leaders, human rights activists and journalists. But five people familiar with the negotiations said that the L3Harris team had brought with them a surprising message that made a deal seem possible. American intelligence officials, they said, quietly supported its plans to purchase NSO, whose technology over the years has been of intense interest to many intelligence and law enforcement agencies around the world, including the F.B.I. and the C.I.A.

The talks continued in secret until last month, when word of NSO's possible sale leaked and sent all the parties scrambling. White House officials said they were outraged to learn about the negotiations, and that any attempt by American defense firms to purchase a blacklisted company would be met by serious resistance.... Left in place are questions in Washington, other allied capitals and Jerusalem about whether parts of the U.S. government — with or without the knowledge of the White House — had seized an opportunity to try to bring control of NSO's powerful spyware under U.S. authority, despite the administration's very public stance against the Israeli firm....

[NSO Group] had seen a deal with the American defense contractor as a potential lifeline after being blacklisted by the Commerce Department, which has crippled its business. American firms are not allowed to do business with companies on the blacklist, under penalty of sanctions. As a result, NSO cannot buy any American technology to sustain its operations — whether it be Dell servers or Amazon cloud storage — and the Israeli firm has been hoping that being sold to a company in the United States could lead to the sanctions being lifted....

L3 Harris's representatives told the Israelis that U.S. intelligence agencies supported the acquisition as long as certain conditions were met, according to five people familiar with the discussions. One of the conditions, those people said, was that NSO's arsenal of "zero days" — the vulnerabilities in computer source code that allow Pegasus to hack into mobile phones — could be sold to all of the United States' partners in the so-called Five Eyes intelligence sharing relationship. The other partners are Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

"Several people familiar with the talks said there have been attempts to resuscitate the negotiations..."

Efforts to Acquire Pegasus Spyware's Company Backed by US Spies, Says Stingray Maker - Slashdot

The New York Times describes Pegasus as "a 'zero-click' hacking tool that can remotely extract everything from a target's mobile phone [and] turn the mobile phone into a tracking and recording device." But they also report that the tool's "notorious" maker, NSO Group, was visited "numerous...

news.slashdot.org

More than 10 million people rely on Ring video doorbells to monitor what's happening directly outside the front doors of their homes. The popularity of the technology has raised a question that concerns privacy advocates: Should police have access to Ring video doorbell recordings without first gaining user consent?

Ring recently revealed how often the answer to that question has been yes. The Amazon company responded to an inquiry from US Senator Ed Markey (D-Mass.), confirming that there have been 11 cases in 2022 where Ring complied with police "emergency" requests. In each case, Ring handed over private recordings, including video and audio, without letting users know that police had access to—and potentially downloaded—their data. This raises many concerns about increased police reliance on private surveillance, a practice that's long gone unregulated.

Ring says it will only "respond immediately to urgent law enforcement requests for information in cases involving imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to any person." Its policy is to review any requests for assistance from police, then make "a good-faith determination whether the request meets the well-known standard, grounded in federal law, that there is imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to any person requiring disclosure of information without delay."

Critics say it shouldn't be left up to Ring and the police to decide when data can be accessed, or how long that data can be stored.

"There are always going to be situations in which it might be expedient for public safety to be able to get around some of the usual infrastructure and be able to get footage very quickly," says Matthew Guariglia, a policy analyst for Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting civil liberties online. "But the problem is that the people who are deciding what constitutes exigent circumstances and what constitutes the type of emergency, all of these very important safeguards, are Ring and the police, both of whom, as far as I know, don't have a great reputation when it comes to deciding when it's appropriate to acquire a person's data."

Amazon finally admits giving cops Ring doorbell data without user consent

Amazon Ring gave police data without user consent 11 times so far in 2022.

Olkaa varovaisia näin älytalo vehkeiden kanssa.

An anonymous reader quotes a report from Wired:

As marketers, data brokers, and tech giants endlessly expand their access to individuals' data and movements across the web, tools like VPNs or cookie blockers can feel increasingly feeble and futile. Short of going totally off the grid forever, there are few options for the average person to meaningfully resist tracking online. Even after coming up with a technical solution last year for how phone carriers could stop automatically collecting users' locations, researchers Barath Raghavan and Paul Schmitt knew it would be challenging to convince telecoms to implement the change. So they decided to be the carrier they wanted to see in the world. The result is a new company, dubbed Invisv, that offers mobile data designed to separate users from specific identifiers so the company can't access or track customers' metadata, location information, or mobile browsing. Launching in beta today for Android, the company's Pretty Good Phone Privacy or PGPP service will replace the mechanism carriers normally use to turn cell phone tower connection data into a trove of information about users' movements. And it will also offer a Relay service that disassociates a user's IP address from their web browsing.

PGPP's ability to mask your phone's identity from cell towers comes from a revelation about why cell towers collect the unique identifiers known as IMSI numbers, which can be tracked by both telecoms and other entities that deploy devices known as IMSI catchers, often called stringrays, which mimic a cell tower for surveillance purposes. Raghavan and Schmitt realized that at its core, the only reason carriers need to track IMSI numbers before allowing devices to connect to cell towers for service is so they can run billing checks and confirm that a given SIM card and device are paid up with their carrier. By acting as a carrier themselves, Invisv can implement their PGPP technology that simply generates a "yes" or "no" about whether a device should get service. On the PGPP "Mobile Pro" plan, which costs $90 per month, users get unlimited mobile data in the US and, at launch, unlimited international data in most European Union countries. Users also get 30 random IMSI number changes per month, and the changes can happen automatically (essentially one per day) or on demand whenever the customer wants them. The system is designed to be blinded so neither INVISV nor the cell towers you connect to know which IMSI is yours at any given time. There's also a "Mobile Core" plan for $40 per month that offers eight IMSI number changes per month and 9 GB of high-speed data per month.

Both of these plans also include PGPP's Relay service. Similar to Apple's iCloud Private Relay, PGPP's Relay is a method for blocking everyone, from your internet provider or carrier to the websites you visit, from knowing both who you are and what you're looking at online at the same time. Such relays send your browsing data through two way stations that allow you to browse the web like normal while shielding your information from the world. When you navigate to a website, your IP address is visible to the first relay -- in this case, Invisv -- but the information about the page you're trying to load is encrypted. Then the second relay generates and connects an alternate IP address to your request, at which point it is able to decrypt and view the website you're trying to load. The content delivery network Fastly is working with Invisv to provide this second relay. Fastly is also one of the third-party providers for iCloud Private Relay. In this way, each relay knows some of the information about your browsing; the first simply knows that you are using the web, and the second sees the sites you connect to, but not who specifically is browsing there. In addition to being included in the two PGPP data plans, customers can also purchase the Relay service on its own for $5 per month and turn it on while connected to mobile data or Wi-Fi.

The carrier is still working to bring its services to Apple's iOS. It's also worth noting that Invisv only offers mobile data; there are no voice calling services.

A Phone Carrier That Doesn't Track Your Browsing Or Location - Slashdot

An anonymous reader quotes a report from Wired: As marketers, data brokers, and tech giants endlessly expand their access to individuals' data and movements across the web, tools like VPNs or cookie blockers can feel increasingly feeble and futile. Short of going totally off the grid forever...

yro.slashdot.org

Telegram, which now claims more than 700 million active users worldwide, has a publicly stated philosophy that private communications should be beyond the reach of governments. That has made it popular among people living under authoritarian regimes all over the world (and among conspiracy theorists, anti-vaxxers, and “sovereign citizens” in democratic countries.)

But the service’s structure—part encrypted messaging app, part social media platform—and its almost complete lack of active moderation has made it “the perfect tool” for the kind of doxing campaigns occurring in Myanmar, according to digital rights activist Victoire Rio.

Telegram Has a Serious Doxing Problem

The encrypted messaging app is a haven for politically motivated vitriol, but users are increasingly bringing threats to targets’ doorsteps.

This structure makes it easy for users to crowdsource attacks, posting a target for doxing and encouraging their followers to dig up or share private information, which they can then broadcast more widely. Misinformation or doxing content can move seamlessly from anonymous individual accounts to channels with thousands of users. Cross-posting is straightforward, so that channels can feed off one another, creating a kind of virality without algorithms that actively promote harmful content. “Structurally, it’s suited to this use case,” Rio says.

The first mass use of this tactic occurred during Hong Kong’s massive 2019 democracy protests, when pro-Beijing Telegram channels identified demonstrators and sent their information to the authorities. Hundreds of protesters were sentenced to custodial sentences for their role in the demonstrations. But with the city split along “yellow” (pro-protests) and “blue” (pro-police) lines, channels were also set up to dox police officers and their families. In November 2020, a telecom company employee was jailed for two years after doxing police and government employees over Telegram. Since then, Telegram doxing appears to be spreading to new countries.

In Iraq, militia groups and their supporters have become adept at using Telegram to source information about opponents, such as leaders of civil society groups, which they then broadcast on channels with tens of thousands of followers. Sometimes, bounties are offered for information, according to Hayder Hamzoz, founder of the Iraqi Network for Social Media, an organization that tracks social media use in the country. Often, these come with direct or implicit threats of violence. Targets have faced harassment and violence, and some have had to flee their homes, Hamzoz says.

In Eastern Europe, where Telegram is a popular platform, several large doxing campaigns have increased in scale and frequency since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Ukrainians have been using Telegram to release the private information of Russian soldiers, politicians, and alleged collaborators and spies, according to open source intelligence experts studying the conflict, who asked to remain anonymous. Russian channels, meanwhile, have been doxing people fighting for Ukraine, often accusing them of being Nazis. Project Nemesis, a large Russian doxing operation, runs a very active Telegram channel, releasing phone numbers, addresses, and other personal information about Ukrainian soldiers.

Activists in countries where doxing has become widespread accuse Telegram of turning a blind eye to the problem.

Experts in social media moderation who have studied Telegram told WIRED that they doubt the company is willing to or capable of systematically addressing its doxing problem. They said that the company, which is thought to employ only a few dozen people worldwide, discloses very little about its corporate structure and publicly names only a handful of its employees. But it has dramatically outgrown its infrastructure. Unlike other platforms, which employ in-house and outsourced moderators (and still struggle to tackle issues of disinformation and harmful content), Telegram has a philosophical, as well as a practical resistance to moderation.

“It’s not just a failure of the platform,” says Aliaksandr Herasimenka, a postdoctoral researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute. “It’s a deliberate stance.”

An EU watchdog says rules that allow Europol cops to retain personal data on individuals with no links to criminal activity go against Europe's own data privacy protections, not to mention undermining the regulator's powers and role.

As such, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) has asked Europe's top court to toss out two amendments to the Europol Regulation that took effect on June 28 enabling this data hoarding by the police.

In court documents filed this month, EDPS claimed the new provisions retroactively legalize Europol's practice of storing personal data on people not linked to criminal activity — a practice the watchdog has sanctioned the law enforcement agency for in the past, and in January ordered Europol to delete such information.

So in summary, EDPS told the police at the start of the year to not hoard these records, and then months later European lawmakers authorized the practice by updating the rules, leading to the supervisor challenging the amendments.

The regulator's order to delete people's data stemmed from an investigation that took place between April 2019 and September 2020, and concluded Europol harvested and retained too much information on too many individuals for far too long.

To remedy this, the order required the European cops to check to see if an individual was linked to criminal activity within six months of collecting their personal data. If those folks had no nefarious ties, then the law enforcement agency was supposed to erase the private information.

"A six-month period for pre-analysis and filtering of large datasets should enable Europol to meet the operational demands of EU Member States relying on Europol for technical and analytical support, while minimizing the risks to individuals' rights and freedoms," EDPS head Wojciech Wiewiorowski said in a statement earlier this year.

The pan-Europe police, for its part, cited [PDF] the nature of long-running criminal investigations as its reason for needing longer retention periods.

Pressure mounts against Europol over data privacy

If you could stop storing records on people unconnected to any crimes, that would be great

vompatti

Kenraali

James Earl Jones, the actor who has voiced iconic Star Wars villain Darth Vader since 1977, has reportedly permitted his past utterances to be fed into an AI that will ensure his distinct tones become replicable once he becomes one with the Force.

News that Vader will achieve digital immortality comes from report in Vanity Fair which reveals that a Ukrainian company called Respeecher was hired by Lucasfilm to reproduce Jones's famous baritone for the Obi-Wan Kenobi miniseries recently released on the Disney+ streaming service.

Respeecher describes itself as offering content creators to "Create speech that's indistinguishable from the original speaker."

James Earl Jones allows AI to take his role as Darth Vader

Ukrainian outfit Respeecher's GAN-based neural audio enhancer embraces The Dark Side

The US intelligence community has launched a program to develop artificial intelligence that can determine authorship of anonymous writing while also disguising an author's identity by subtly altering their words.

The Human Interpretable Attribution of Text Using Underlying Structure (HIATUS) program from the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) aims to build software that can perform "linguistic fingerprinting," the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) said.

"Humans and machines produce vast amounts of text content every day. Text contains linguistic features that can reveal author identity," IARPA said [PDF].

With the right model, IARPA believes it can identify consistencies in a writer's style across different samples, modify those linguistic patterns to anonymize writing and do it all in a manner that is explainable to novice users, ODNI said. HIATUS AIs would also have to be language agnostic.

"We have a strong chance of meeting our goals, delivering much-needed capabilities to the Intelligence Community, and substantially expanding our understanding of variation in human language using the latest advances in computational linguistics and deep learning," said HIATUS program manager Dr Timothy McKinnon.

In order to develop strong models, HIATUS plans to approach its goals as a question of adversarial AI: Authorship attribution and anonymizing text are two sides of the same problem, and so HIATUS experiment groups will be pitted against each other.

"Attribution systems are evaluated on ability to match items by the same author in large collections, while privacy systems are evaluated on ability to thwart attribution systems," IARPA said.

The agency said it also plans to develop explainability standards for HIATUS AIs.

McKinnon said that part of what HIATUS is doing is trying to demystify some of the unknowns around neural language models (the focus of HIATUS' efforts), which he said work well but are essentially black boxes that function without their developers knowing why they make a particular decision.

US government wants AI that can ID text's author

Along with revealing authors, IARPA also wants bot to disguise scribes

Sanavalmis Muurinen

Kenraali

Kaupunginvaltuutettu (ps, Hki) Väyrysen linjoilla: kaikkihan tässä johtuu vain suurvaltojen ristiriidoista tietenkin

On Friday, Ars Technica reported that Bruce Willis had sold his likeness for use in deepfakes, according to The Telegraph. Dozens of news sites repeated the Telegraph's claim. Over the weekend, the BBC discovered that Bruce Willis has "no partnership or agreement" with the firm Deepcake, which is based in Georgia, the Eurasian republic.

It's unclear how the inaccurate claim originated at The Telegraph. While reporting last Friday, we attempted to verify some of the claims in the original Telegraph article (such as Willis being the first actor to sell his deepfake rights), but we could not do so, and we noted that in the report. We also noted that Deepcake is doing business in America under a corporation registered in Delaware. However, we failed to follow through with verifying the entire claim, and we apologize for the error and for repeating the erroneous information.

Bruce Willis denies selling deepfake rights to Deepcake

Willis' agent: "Bruce has no partnership or agreement with this Deepcake company."

In a paper titled Chat Control or Child Protection?, to be distributed via ArXiv, Anderson offers a rebuttal to arguments advanced in July by UK government cyber and intelligence experts Ian Levy, technical director of the UK National Cyber Security Centre, and Crispin Robinson, technical director of cryptanalysis at Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the UK's equivalent to the NSA.

That pro-snoop paper, penned by Levy and Robinson and titled Thoughts on Child Safety on Commodity Platforms, was referenced on Monday by EU Commissioner for Home Affairs, Ylva Johansson, before the European Parliament’s Civil Liberties (LIBE) Committee in support of the EU Child Sexual Abuse Regulation (2022/0155), according to Anderson.

The occasion for the debate is the approaching August 3, 2024 expiration of an EU law that authorizes online service providers to voluntarily detect and report the presence of child sexual abuse material in users' communications and files. Without replacement rules, supporters of the proposed child safety regime argue that harmful content will be ignored.

But online rights groups contend the contemplated legislation would cause its own harm.

"The proposed EU Child Sexual Abuse Regulation is a draft law which is supposed to help tackle the spread of child sexual abuse material," said the European Digital Rights Initiative (EDRi), in response to Johansson's proposal.

"Instead, it will force the providers of all our digital chats, messages and emails to know what we are typing and sharing at all times. It will remove the possibility of anonymity from many legitimate online spaces. And it may also require dangerous software to be downloaded onto every digital device."

Meanwhile the UK is considering its own Online Safety Bill, which also imagines bypassing encryption via device-side scanning. Similar proposals, such as the EARN IT bill, keep surfacing in the US.

The paper by Levy and Robinson – itself a response to a paper opposing device-side scanning that Anderson co-authored with 13 other security experts in 2021 – outlines the various types of harms children may encounter online: consensual peer-to-peer indecent image sharing; viral image sharing; offender to offender indecent image/video sharing; offender to victim grooming; offender to offender communication; offender to offender group communication; and streaming of on-demand contact abuse.

Anderson argues that this taxonomy of harms reflects the interests of criminal investigators rather than welfare of children. "From the viewpoint of child protection and children’s rights, we need to look at actual harms, and then at the practical priorities for policing and social work interventions that can minimize them," he says.

Anderson calls into question the data used to fuel media outrage and political concern about harms to children. Citing the 102,842 reports from National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), the US-based non-profit coordinating child abuse reports from tech firms, to the UK's National Crime Agency (NCA), he estimates that this led to 750 prosecutions for indecent images, "well under 3 percent of the 2019 total of 27,233 prosecutions for indecent image offences, of which 26,124 involved images of children." And the number of such prosecutions peaked in 2016 and has since fallen, he says.

"In short, the data do not support claims of large-scale growing harm that is initiated online and that is preventable by image scanning," says Anderson.

Client-side scanning to detect child abuse material harmful

Security expert challenges claim that bypassing encryption is essential to protecting kids

Tikka

Kersantti

Propagandaa ja psyopseja. Sylttytehtaalta hevosen suusta, GRU unit 54777. Iltalukemiseksi, jos ei jo ole tuttu (vuodelta 2020).

www.4freerussia.org

www.4freerussia.org

Aquarium Leaks. Inside the GRU’s Psychological Warfare Program

In this exclusive and groundbreaking report, Free Russia Foundation has translated and published five documents from the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency. The documents, obtained and analyzed by Free Russia Foundation’s Director of Special Investigations Michael Weiss, details the...