Paavi taitaa olla hieman ulkona maailman menosta. Jos Korean sota II syttyy, niin se on PK vs Muu maailma.

Tai sitten hän on ainoa ihmiskunnasta joka tietää. Kuullut juttua, että Vatikaaninpojilla olisi suora linja yläkerran väkeen.

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Paavi taitaa olla hieman ulkona maailman menosta. Jos Korean sota II syttyy, niin se on PK vs Muu maailma.

http://yle.fi/uutiset/3-9589984Japani lähettää sotalaivansa suojelemaan Yhdysvaltojen laivaston tukialusta. Syynä on Pohjois-Korean jännittynyt tilanne. Matkaan lähtevä Izumo on Japanin laivaston suurin alus.

On tosin vaikea nähdä miksi ihmeessä mies kylmän sellaisen päästäisi. Kansalleen kerrotun tarinan mukaanhan miehen kroppa on niin hyvin kalibroitu ettei tarvitse edes p*skalla käydä...:

Joo. Olen pitkään ihaillut Kimiä, koska hänen kehonsa suorastaan huokuu juurikin tuota äärimmäisyyksiin viritettyä metabolista kalibraatiota

Japanin vai Kiinan mielestä ei pitäisi olla olemassa249 metriä pitkä jättiläinen, jota ei pitäisi olla olemassa – tällainen alus on Japanin kiistelty ylpeys Izumo

Hyvä että lähettivät. Uumoilinkin asiaa jokin aika sitten..

Hyvä että lähettivät. Uumoilinkin asiaa jokin aika sitten..http://www.independent.co.uk/news/w...-tests-maximum-war-trump-latest-a7711236.htmlNorth Korea suggested on Monday it will continue its nuclear weapons tests, saying it will bolster its nuclear force "to the maximum" in a "consecutive and successive way at any moment" in the face of what it calls U.S. aggression and hysteria.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/01/north-korea-missile-defence-donald-trump-thaad-seoulThe South Korean media has accused Donald Trump of weakening bilateral security ties at a time of heightened tensions on the Korean peninsula after he said Seoul should pay for a controversial missile defence system.

The US president was accused of dropping “a barrage of verbal bombs” and sending “confusing and contradictory” messages over Washington’s commitment to the country’s security.

“I informed South Korea it would be appropriate if they paid. It’s a billion-dollar system,” Trump was quoted as saying by the Reuters news agency. “It’s phenomenal, shoots missiles right out of the sky.”

However, Trump’s national security adviser, HR McMaster, reportedly told his South Korean counterpart on Sunday that the US would shoulder the costs for the system, which is designed to intercept North Korean missiles in mid-flight.

The leading Chosun Ilbo newspaper said Trump was placing domestic financial concerns above regional security, at a time when North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes were causing alarm among its neighbours.

“Trump’s mouth rattling Korea-US alliance,” it said in a front-page headline. “There are issues that are far more important than just money,” it said in an editorial. “If either country keeps reducing the alliance to the matter of money or the economy, it is bound to undermine basic trust.”

Washington’s position on which country should pay for Thaad is still unclear, however, with McMaster suggesting that payment was still up for negotiation. “The relationship on Thaad, on our defence relationship going forward, will be renegotiated, as it’s going to be with all of our allies,” he told Fox News on Sunday.

The US and South Korea originally agreed that Washington would pay for Thaad in return for South Korea providing land for missile batteries, radar and other facilities.

Ydinkoe nyt olisi valtava keskisormen heilutus Kiinalle, koko maailman edessä. Veto-oikeuden käyttäjä on luultavasti ystävämme Venäjä, joka taas leikkii sorrettujen ja väärinymmärrettyjen diktaattorien pelastajaa.http://www.independent.co.uk/news/w...-tests-maximum-war-trump-latest-a7711236.html

Ydinkoe lähestyy. Trump ei reakoinut ohjuskokeeseen, jos hän ei tee mitään koeräjäytyksen jälkeen, niin PK voittaa tilanteen. YKlla ei ole munaa sotilastoimenpiteeseen Kiinan käyttäessä veto-oikeuttaan.

http://www.defenseone.com/ideas/201...ea-need-get-same-page/137456/?oref=d-topstoryEven as the United States and her Pacific allies coalesce around a shared belief that new measures must be taken with regard to North Korea, mutual mistrust and diverging priorities make it harder to choose a path forward.

Last August, well before the current sense of crisis, these gaps in coordination and trust were highlighted at the annual US-ROK-Japan Trilateral Strategic Dialogue. Hosted by Pacific Forum CSIS with the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, the event brings together experts, officials, military officials, and observers from the three countries to simulate a North Korea crisis. Its goal is to find areas of convergence in strategic and tactical goals, but more importantly, to find divergence among the partners. Here are some of the issues that remain unresolved, even as last year’s simulation draws closer to reality.

Nuclear attack aside, Seoul’s 10 million residents live within minutes of North Korea’s heavy artillery, short-range ballistic missiles, and chemical weapons. Within this population is about 60,000 Japanese nationals, whose evacuation during a crisis would seem like a standard operating procedure. However, even this planning has become a thorny issue in ROK-Japan strategic planning. Given the sensitivities in South Korea over Japan’s former colonization of the Peninsula, the thought of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces on Korean soil, even to help with a noncombatant evacuation operation (NEO), stokes anger among South Koreans. This became apparent during the simulation, and again just a few weeks ago, when Japan’s National Security Council and Defense Minister Tomomi Inada both talked about the possibility of deploying Japanese troops to protect and evacuate its Korea-dwelling citizens in a crisis. Seoul was quick to express displeasure, with one official suggesting that Japan refrain from remarks that “can have a negative influence on the peace and security of the Peninsula.” South Korean social media was less forgiving, with some netizens suggesting that Japan is waiting for war, as it will “be an excuse to make its Self-Defense Forces stronger.” The ROK-Japan inability to cooperate on something as soft as a NEO casts doubt on their ability to respond to a crisis.

When it comes to China, all three countries agree that cooperation and coordination with Beijing during a crisis will be key, but they diverge tactically. South Korea, whose need for a positive relationship with Beijing is a geopolitical fact, prefers full transparency and clarity in its messaging to China; South Korea’s need to work with China in any post-Kim Jong-un environment is also a driving factor. Conversely, the U.S. favors a more opaque stance in its China messaging so as not to give Beijing an opportunity to thwart any war aims. Today’s political setting threatens to exacerbate this issue. President Trump, who has frequently dismissed tactical transparency, shows no signs that he would share any military strategy with China during a North Korea crisis. Moon Jae-in, South Korea’s progressive presidential front-runner, may seek to reset relations with North Korea and China. Moon has expressed interested in reopening the Kaesong Industrial complex and perhaps even attempting a summit with Kim Jong-un. Whether he would share tactical plans with China during a crisis is unknown, but how the U.S. and ROK message with China is likely to be an area of contention.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2...rhetoric-threatening-nuclear-test-at-any-timeNorth Korea has vowed to accelerate its nuclear weapons programme to “maximum pace” and test a nuclear device “at any time” in response to Donald Trump’s aggressive stance towards the regime.

The warning came as US military officials said a controversial missile defence system was now “operational” after being installed at a site in South Korea last week

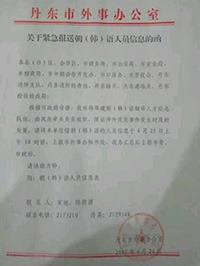

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2017/05/103_228584.htmlA Chinese town near the border with North Korea is "urgently" recruiting Korean-Chinese interpreters, stirring speculation that China is bracing for an emergency situation involving its nuclear-armed neighbor.

The Oriental Daily, a Hong Kong-based news outlet published the story on Apr. 27, including a photo of a Chinese government document ordering the town of Dandong to recruit an unspecified number of Korean-Chinese interpreters to work at 10 departments in the town, including border security, public security, trade, customs and quarantine.

The document did not specify the reason for the unusual, large-scale recruiting. But experts and local citizens said the move indicated that China was bracing for a possible military clash between the United States and North Korea.

This might trigger a huge exodus of North Koreans to border towns in China.

Whether this dismal scenario will become a reality is largely up to North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un.

U.S. President Donald Trump has repeatedly warned that the world's superpower will strike North Korea's nuclear facilities if Kim proceeds with a sixth nuclear test or test fires an intercontinental ballistic missile.

The Dandong administration also has ordered its officials to work rotating night shifts since April 25, according to South Korea's news agency Yonhap.

Meanwhile, China has dismissed reports that it has sent 150,000 additional troops to its border with the North.

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-usa-idUSKBN17W04TNorth Korea accused the United States on Tuesday of pushing the Korean peninsula to the brink of nuclear war after a pair of strategic U.S. bombers flew training drills with the South Korean and Japanese air forces in another show of strength.

The two supersonic B-1B Lancer bombers were deployed amid rising tensions over North Korea's dogged pursuit of its nuclear and missile programs in defiance of United Nations sanctions and pressure from the United States.

The flight of the two bombers on Monday came as U.S. President Donald Trump said he was open to meeting North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in the right circumstances, and as his CIA director landed in South Korea for talks.

South Korean Defense Ministry spokesman Moon Sang-gyun told a briefing in Seoul that Monday's joint drill was conducted to deter provocations by the North and to test readiness against another potential nuclear test.

The U.S. air force said in a statement the bombers had flown from Guam to conduct training exercises with the South Korean and Japanese air forces.

North Korea said the bombers conducted "a nuclear bomb dropping drill against major objects" in its territory at a time when Trump and "other U.S. warmongers are crying out for making a preemptive nuclear strike" on the North.

"The reckless military provocation is pushing the situation on the Korean peninsula closer to the brink of nuclear war," the North's official KCNA news agency said on Tuesday.

Kiinan johto vaatii edelleen USA:ta vetämään THAAD-järjestelmänsä pois Koreasta:

http://mobile.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN17Y0VF?mod=related&channelName=BigStory12

"We will resolutely take necessary measures to defend our interests," Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang told a daily news briefing, without elaborating.

Aika vahvaa tekstiä, tiedä sitten mitä nuo keinot pitävät sisällään. Ohjuskilpi saattaa vielä pahimmassa tapauksessa estää Kiinan ja USA:n yhteistyön P-Korean tilanteen ratkaisemisessa.

Japanin vai Kiinan mielestä ei pitäisi olla olemassaHyvä että lähettivät. Uumoilinkin asiaa jokin aika sitten..

. Japanin oppositio on aina ollut epäluuloinen JSDF:ää kohtaan, jotkut jopa varsin vihamielisiä.

. Japanin oppositio on aina ollut epäluuloinen JSDF:ää kohtaan, jotkut jopa varsin vihamielisiä. The Japanese populace remains sharply divided over whether to amend the war-renouncing Article 9 of the Constitution, with supporters of a change slightly outnumbering opponents amid concerns over North Korea and China’s military buildup, a newly released Kyodo News survey showed.

According to the mail-in survey, which was conducted ahead of Wednesday’s 70th anniversary of the postwar Constitution’s enactment, 49 percent of respondents said Article 9 must be revised while 47 percent oppose such a change.

While Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has been eager to rewrite the supreme law, including Article 9, 51 percent were against any constitutional amendments under the Abe administration, compared with 45 percent in favor.

Many people recognized the role Article 9 has played in maintaining the nation’s pacifist stance, with 75 percent of respondents saying the clause has enabled the country to avoid becoming embroiled in conflicts abroad since World War II.