https://carnegieendowment.org/russi...soline-politics?lang=ru¢er=russia-eurasia

The Price of Dirigisme. How Government Regulation Led the Russian Gasoline Market to Crisis

The damper was supposed to relieve the Russian economy and the average consumer from the harmful effects of unstable market conditions. But in the long term, it turns out that the problems it was supposed to solve didn't actually exist, or were insignificant, while the resulting distortions are growing and becoming increasingly costly.

Sergey Vakulenko

September 2, 2025

The Russian Federation has added the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to its list of "undesirable organizations." If you are located in Russia, please do not publicly link to this article.

Russia regularly experiences "gasoline crises"—periods of localized fuel shortages and rising prices. The immediate trigger is usually a seasonal increase in demand due to agricultural work and summer vacations, as well as a decrease in supply due to scheduled maintenance at refineries.

In theory, the Russian oil industry should be able to easily cope with such seasonal fluctuations thanks to its impressive size. However, the Russian motor fuel market is structured in such a way that price signals are dampened. This makes it unprofitable for individual suppliers to react to changing market conditions. This indifference is the price paid for the government's attempts to stabilize fuel prices.

The government's main tool for achieving price stability is the "damper mechanism." It has been in use since 2019, and, according to the authorities, it has repeatedly proven its effectiveness. However, a careful analysis of how the Russian gasoline market has developed over the past decade reveals that such regulation may actually do more harm than good.

From Duties to a Damper

What is the price of gasoline at the pump? Let's imagine this is happening in a country that imports gasoline at global prices. These prices depend primarily on the price of the raw material, namely, oil. Gasoline typically trades at a 25-27% premium to Brent crude oil on the exchange. This is understandable: oil refineries need to cover operating costs and still make some money. However, "usually" doesn't mean "always." For example, in March 2020, the difference between the gasoline and crude oil exchange prices (the gasoline refining spread) was -26%. In May 2022, it was +67%. The first case was a response to the COVID-19 lockdown, the second to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

If our hypothetical country is located far from where gasoline is produced, it will also have to pay for transportation ($2-4 per barrel). Plus, local wholesalers and retailers will want their share of the profits (the retail spread). Finally, VAT will be charged on the sales price.

So, the price of gasoline at the pump is the global oil price + gasoline refining spread + transportation costs + retail spread + VAT + possibly excise tax.

Now consider the situation in a country producing and exporting gasoline. The first three elements of the formula are replaced by the "export alternative price." In the simplest case, this is the global exchange price of gasoline minus the cost of transportation from that country to the exchange. If a refinery owner sells gasoline in their own country, they won't have to pay for delivery to a distant market. In other words, selling at a lower price in their own country will make the same profit as selling at a higher price in a distant market.

It doesn't matter whether gasoline is produced from imported oil or from domestically produced oil. If exports are unlimited, the price at which a refinery is willing to sell oil domestically cannot be lower than the export revenue minus transportation costs. It may be higher if the market is not very competitive for some reason. Below, however, the differences are limited to the extent that real production and supply chains differ from ideal models capable of instantly responding to market signals, and only during the period of market rebalancing. The price and terms of the plant's purchase of raw materials for the production of the final product are completely irrelevant.

The wholesale gasoline market is global, so this price component is essentially dollar-denominated and depends, among other things, on the national currency exchange rate. If the national currency weakens against the dollar, then, with a constant dollar price for gasoline on global wholesale markets, the price at the pump in rubles, dinars, or, say, euros should also rise. Excise taxes in most countries are set in the national currency, and the desired retail margin also includes a significant component of local cost factors, but the price of gasoline itself is a dollar element.

For many years, the specifics of monetary policy in Russia were determined by a compensatory mechanism: when oil prices rose on the international market, the ruble strengthened, and vice versa. Thus, the global price of gasoline, converted into rubles, remained relatively stable.

The government can influence the size of the export alternative: it will decrease if an export duty is imposed. Let's assume gasoline sells for $100 per barrel in Rotterdam, transportation to that port costs $4 per barrel, and the Rotterdam market depth is unlimited. Under these conditions, selling gasoline wholesale in St. Petersburg for less than $96 per barrel makes no sense. But if an export duty of $20 per barrel is required upon export, then selling in St. Petersburg for $76 becomes profitable. If the seller exports gasoline, the $20 goes to the government, and if they sell domestically, the domestic buyer benefits: they get gasoline cheaper than foreigners. The duty acts as a wedge between foreign and domestic prices.

This is precisely how things worked in Russia throughout the 2000s and 2010s. There was an export duty on oil and petroleum products, with the former being higher: the government stimulated the export of petroleum products and also lowered domestic prices relative to foreign markets.

Since the early 2010s, Russia has been discussing a tax maneuver, and in 2015, implementation began. The idea was to gradually eliminate the export duty on both oil and petroleum products. Before the tax maneuver, the state collected part of the natural resource rent from oil production at the well in the form of a mineral extraction tax (MET), and part from exports in the form of an export duty, which benefited domestic consumers. After the maneuver, all rent was to be collected at the well, regardless of where the product was subsequently sold.

At the same time, the state began systematically increasing the excise tax on petroleum products. As a result, while in 2015 the price of a liter of gasoline in Russia still included a subsidy derived from the still-high export duty and the low excise tax of approximately 3 rubles per liter of 92-octane gasoline, by early 2018, the combination of the increased excise tax and the decreasing duty wedge had led to the effective excise tax accounting for approximately 8.5 rubles per liter. In other words, within three years, indirect taxes had come to account for approximately 25% of the price per liter.

In the spring of 2018, global oil and gasoline prices began to rise noticeably, while the ruble simultaneously weakened. This led to a sharp increase in the effective price of gasoline as an export alternative. The government had always told major Russian oil companies that they should be socially responsible and not increase fuel prices for end consumers too quickly, maintain a wide range of gasoline at their stations, and sell sufficient wholesale volumes to independent retailers. In 2018, the companies did comply with the first two points, but they refused to sell gasoline to domestic wholesalers at a "socially responsible" price lower than the export alternative. As a result, independent gas stations ran out of gasoline, and a "fuel crisis" ensued.

Even without the ability to export gasoline and without the alternative value of gasoline in the form of the export alternative price, Russian oil companies would still not have been able to maintain their existing gasoline prices given the rising global oil price and the declining ruble. It would seem that companies primarily produce fuel from the same oil they extract themselves, rather than buying it on the market. And their production costs are primarily in rubles. Why then is there a link to the global dollar price? The technical cost of oil production isn't limited to this. As soon as a ton of oil passes the fiscal meter at the entrance to the main pipeline, the company must pay a mineral extraction tax (MET) to the budget, which is calculated based on the current dollar price of oil on global markets. In 2018, the marginal MET rate was 50%, meaning that for every $10 increase in the oil price, the MET increased by $5, and companies could not avoid including these costs in the price of gasoline.

To increase the attractiveness of domestic sales while preventing gas station prices from rising, the government took a number of measures. For example, the excise tax was reduced by almost 3 rubles per liter by the end of 2018, and companies were strictly warned about the need for socially responsible behavior. But it was immediately clear that such manual control wouldn't go far. So the government began searching for a way to permanently stabilize prices. The result of this search was the damper mechanism, which was launched in July 2019.

Under this mechanism, an indicative exchange price for gasoline is set annually. Initially, it was assumed that it would be indexed by 5% annually. In 2023, the indexation rate was reduced to 3% per year. Large oil companies are required to sell a significant share of their gasoline production on the exchange. If the exchange price is lower than the export alternative price, the companies receive 68% of the difference from the budget. If it is higher, they pay the same 68% of the difference to the budget.

This is equivalent to a situation in which companies would enter into a swap transaction between the export alternative price and the Russian exchange price, albeit with an additional condition: the transaction is valid only within a 10% range around the indicative price. If average monthly exchange prices in a given month are above the upper limit of the corridor, even if they were significantly lower than the export alternative price, companies will not receive reimbursement from the budget.

Let's explain the economic rationale behind this scheme. The government continues to keep the input price of oil for refiners high, maintaining the level of production taxes. To reduce gasoline prices domestically, oil companies are required to sell it below its actual cost at this level of domestic oil prices. Part of their losses are compensated through a damping mechanism, derived from the same production tax. Technically, this is done even more simply: when calculating the oil production tax, the deduction due under the damping mechanism is taken into account.

This scheme assumes, firstly, that the state does not fully compensate for losses. Secondly, companies assume an increasing share of the costs of maintaining stable prices. The damping mechanism is based on a frankly unrealistic level of gasoline price growth, especially given the government's actions: in 2022–2023, the excise tax on gasoline, which is part of the exchange price, increased annually by 4%, in 2024 by 5%, and in 2025 by 13.6%. The excise tax now accounts for about a quarter of the price of a liter, so this increase is very significant.

The complex structure that has emerged is designed in such a way that the well-being of each player depends on the behavior of others. When the exchange price approaches the corridor boundary, the risk arises that compensation will not be provided. Then, major players can, for example, maintain hope that the threshold will not be breached and behave cooperatively, placing sell orders at a price slightly below the threshold. Or one of them might lose hope and start selling above the threshold, prompting other players to follow suit. Therefore, after crossing the threshold, the price immediately jumps higher, and then has little chance of returning to the damper's operating range by the end of the month. This is precisely the effect observed on the gasoline exchange during the current crisis.

The first major gasoline crisis of the damper era occurred in 2023. At that time, all Russian government agencies were faced with the task of finding sources of additional budget revenue and reducing costs. One solution was to halve payments under the damper mechanism: oil companies began paying 34% of lost revenue from domestic sales instead of 68%. Naturally, no one planned to reduce the mineral extraction tax on oil, the maximum rate of which reached 75% by 2023.

In response, oil companies predictably began to reduce their sales on the exchange, although they maintained sales through their own gas station networks. The government responded with a ban on gasoline exports (forcing companies to either sell domestically or significantly reduce refining volumes) and threats of antitrust investigations, but ultimately restored the previous level of compensation. Since then, authorities have annually banned gasoline exports during the summer as a preventative measure.

The Illusion of Need

The Russian government introduced the damper system for several reasons. Rising gasoline prices are hitting consumers hard, fueling discontent with economic policy and fueling inflation expectations (the widespread belief is that fuel consumption accounts for a large portion of the cost of many goods). Furthermore, people see this as further proof that oil companies are making excess profits from the fuel trade, regardless of the price environment.

Public discontent is a problem for the government, regardless of how justified it is. But to what extent do these widespread perceptions correspond to reality?

The relationship between inflation and rising fuel prices has been examined in numerous studies. Some are empirical, while others are based on input-output matrices and input-output tables, popular in Russia since the Gosplan era. It turns out that even in agricultural production—a relatively fuel-intensive sector that produces low-cost goods—the share of petroleum products in the final product price does not exceed 10%, so even a 10% increase in petroleum product prices only increases production costs by 1%. Indeed, rising retail prices for petroleum products significantly increase citizens' inflation expectations, which affects their economic behavior.

Importantly, long-term stabilization of fuel prices—at a lower level at that—forces the government to implement long-term subsidies for gasoline consumption, a policy it attempted to abandon in the mid-2010s through a tax maneuver. Extensive global experience demonstrates the disadvantages of such subsidies. The longer it persists, the harder and more painful it is to give it up. But maintaining it is even more painful, for both importers and exporters of energy resources.

The high level of monopolization of the oil product market in Russia was cited as another reason for dirigism in the pricing of petroleum products. It was claimed that without such dirigism, market participants were inclined to raise gasoline prices under any circumstances and extract excessively high margins—and the indicative pricing mechanism supposedly effectively combats this.

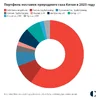

To understand whether this is true, let's compare the dynamics of retail gasoline prices in Russia, the EU, and the US.

The "strange" behavior of gasoline prices was observed only in ruble terms, but disappeared when converted to dollars. After the introduction of the damper, the ruble price trend persisted, but the correlation between the dollar-based price and prices in other markets weakened significantly.

Let's also compare the margins in petroleum product trade in Russia with those in other countries. In the US, the small-scale wholesale margin (the difference between distributor prices and the retail price) is tracked by the industry press. In Poland, for example, this value can be tracked because Orlen, a key player in the local market, publishes a long history of small-scale wholesale prices, while retail price information is available on the European Commission website. In Russia, large-scale wholesale and retail prices can be determined from open data, but the small-scale wholesale margin has to be estimated—to bring it into line with European and American denominators—based on fragmented data.

Nevertheless, based on these data and professional experience, it can be concluded that the small-scale wholesale margin for gasoline sales in Russia is relatively stable and, in the long term, amounts to approximately 3 rubles per liter of gasoline including VAT. With this adjustment, the retail margin can be calculated. It turns out that there have been no excess profits in the Russian fuel market. Therefore, from this perspective, there was no need for dirigisme.

In the US, this figure is calculated per gallon (3.79 liters) and was for a long time significantly lower than both Russian and Polish figures. However, in recent years, it has increased and is now almost equal to these figures.

Ultimately, the current system of gasoline price regulation in Russia is a prime example of "modern dirigisme," the desire to free the economy and the average consumer from the harmful effects of unstable market conditions using quasi-market and, at first glance, elegant technocratic tools, rather than crude manual control. In the short term, this works. But over the longer term, it becomes clear that the problems addressed by these sophisticated tools were either nonexistent or insignificant, while the resulting distortions are growing and becoming increasingly costly to the economy.

A link that opens without a VPN is here.

Pakotteet vahingoittavat pääasiassa ulkomaisia yrityksiä, jotka jatkavat toimintaansa Venäjällä, kun taas Venäjän talous on sopeutunut rajoituksiin ja tuntuu varsin luottavaiselta, kertoo Amerikan kauppakamari Venäjällä.

Pakotteet vahingoittavat pääasiassa ulkomaisia yrityksiä, jotka jatkavat toimintaansa Venäjällä, kun taas Venäjän talous on sopeutunut rajoituksiin ja tuntuu varsin luottavaiselta, kertoo Amerikan kauppakamari Venäjällä.