Samaan aikaan kun kaveri kauhistelee muslimimaailman takapajuisuutta, esittää sen tavallisen uskonkappaleen, siis että länsimaat ovat syypäitä koska "syrjäyttivät" Nasserin, Mossadeqin ym. Afghanistanin sotiin ei myöskään Neuvostoliitto ole syyllinen, vaan Yhdysvallat joka aseisti miehittäjän vastustajia..En keksinyt jutulle muutakaan lankaa.

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Suurmoskeija

- Viestiketjun aloittaja hansai

- Aloitus PVM

Coffee Man

Respected Leader

Samaan aikaan kun kaveri kauhistelee muslimimaailman takapajuisuutta, esittää sen tavallisen uskonkappaleen, siis että länsimaat ovat syypäitä koska "syrjäyttivät" Nasserin, Mossadeqin ym. Afghanistanin sotiin ei myöskään Neuvostoliitto ole syyllinen, vaan Yhdysvallat joka aseisti miehittäjän vastustajia..

Tuossa sopassa on niin monta keittäjää, että vaikea sieltä on poimia ne suurimmat syylliset

Paikallisten lisäksi soppaa ovat hämmentäneet suunnilleen kaikki suurvallat idässä ja lännessä.

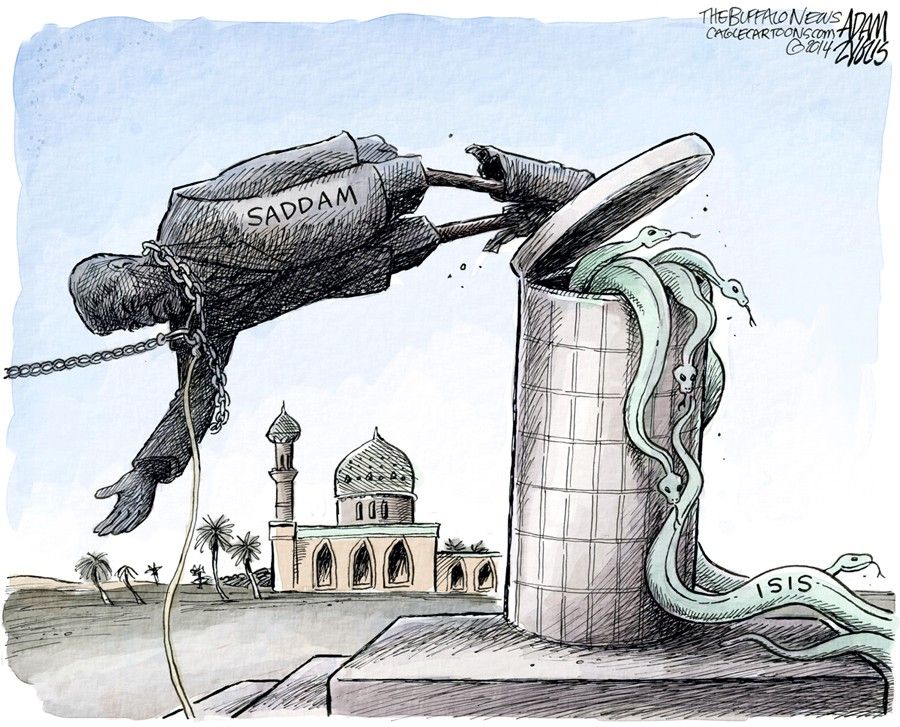

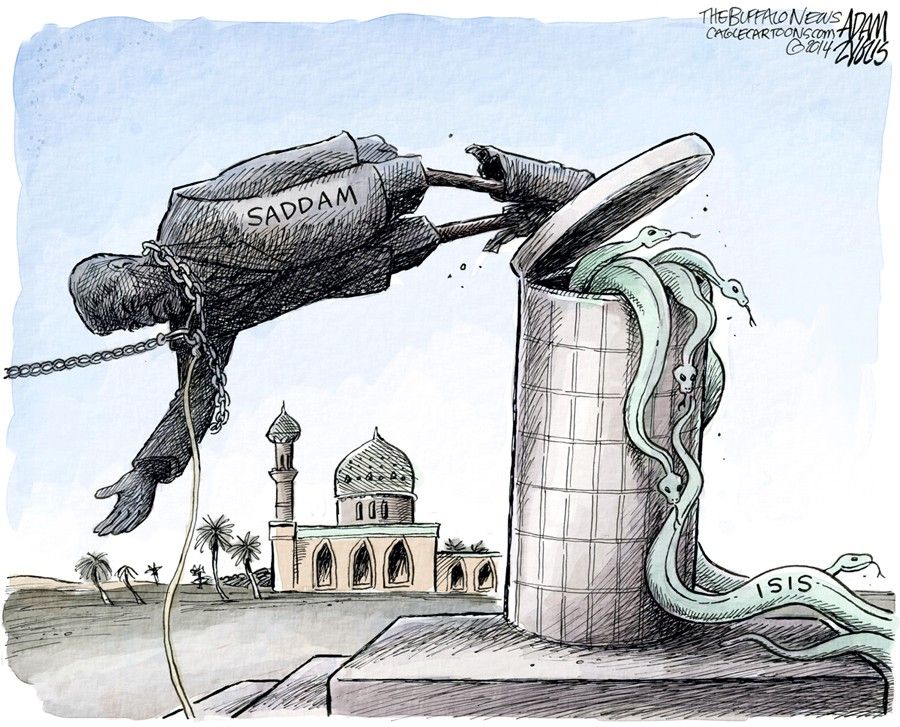

Paikallisten lisäksi soppaa ovat hämmentäneet suunnilleen kaikki suurvallat idässä ja lännessä.Minä lähden kuitenkin siitä että George ja Saddam oli se yhtälö joka sai tämän nykyisen porinan aikaiseksi...

Ja kuten hommaan kuuluu ja on aina kuulunut, niin tässäkin sopassa on taas enemmän niitä kokkeja kun soppaa.

USA, Ranska, Venäjä, Turkki, Israel, Saudi-Arabia ja mitä näitä nyt olikaan.

Tuossa sopassa on niin monta keittäjää, että vaikea sieltä on poimia ne suurimmat syyllisetPaikallisten lisäksi soppaa ovat hämmentäneet suunnilleen kaikki suurvallat idässä ja lännessä.

Minä lähden kuitenkin siitä että George ja Saddam oli se yhtälö joka sai tämän nykyisen porinan aikaiseksi...

Ja kuten hommaan kuuluu ja on aina kuulunut, niin tässäkin sopassa on taas enemmän niitä kokkeja kun soppaa.

USA, Ranska, Venäjä, Turkki, Israel, Saudi-Arabia ja mitä näitä nyt olikaan.

USA ja liittolaiset tekivät rakentavan laatuisen virheen lakkauttaessaan Saddamin turvallisuusorganizaation tuosta vaan. Se aiheutti tyhjiön, jota sitten täyttivät kaikenlaiset aseryhmät...ja lisäksi maa oli sen jälkeen täynnä vittuuntuneita ex-poliiseja ja sotilaita ilman duunia. Hyvä liike, nehän perustivat sitten heti AQI:n ja muuta kivaa. Varmasti noita on edelleenkin ISIS-riveissä tms.

USA et all on nyt 14 vuotta koettanut rakentaa Irakiin turvallisuusorganisaatiota kymmenillä miljardeilla...tunnetuin tuloksin. Kyseyn vaan, että kannattiko...hommat olisi voinut hoitaa toisinkin.

Honcho

SMLNKO M/83

Tästä ei varmaan kannata tehdä mitään johtopäätöksiä Suomen suur....eiku keskusmoskeijan suhteen?

http://www.iltalehti.fi/ulkomaat/201710042200436463_ul.shtml

Belgia karkottaa suurmoskeijan pääimaamin - ”kansakunnan turvallisuudelle vaarallinen mies”

http://www.iltalehti.fi/ulkomaat/201710042200436463_ul.shtml

Belgia karkottaa suurmoskeijan pääimaamin - ”kansakunnan turvallisuudelle vaarallinen mies”

Belgian turvallisuuspalvelu oli pyytänyt ulkomaalaisvirastoa lakkauttamaan imaamin oleskeluluvan, koska tämä on radikaali salafisti, wahhabisti ja sharia-lain kannattaja, jolla on vanhoillisia ja ”erittäin radikaaleja” ajatuksia belgialaista yhteiskuntaa vastaan.

***

Valtiosihteeri Frankenin mukaan radikaalisaarnojen lisäksi moskeijan ongelmana on myös se, että sen rahoituksesta vastaa Saudi-Arabia.

***

RTBF:n tavoittama pääimaami Abdelhadi Sewif ihmettelee oleskelulupansa lakkauttamista sekä Frankenin syytöksiä. Sewif vakuuttaa saarnanneensa aina modernin islaminopin mukaan. Lisäksi hän sanoo, että jos moskeijat saisivat nykyistä enemmän julkista tukea, ei ulkomaisia rahoituslähteitä tarvittaisi (Honcho: taitaa äijä ajatella, että molempi parempi. Mikäs sen mehukkaampaa kuin saarnata lännen rappiota länsimaidenKIN rahalla)

Tästä ei varmaan kannata tehdä mitään johtopäätöksiä Suomen suur....eiku keskusmoskeijan suhteen?

Ei ku meille tulee kaikille avoin uskontojen kohtauspaikka, eikä rahoitukseen liity mitään epäselvää ja hanke auttaa kaikkia integroitumaan keskenään. Kunnon mentaaliorgiat tiedossa

https://www.talouselama.fi/uutiset/...-dd1a-3aca-88c6-c07f59767097?ref=twitter:204eSuurmoskeijahanke laskeutui loppusuoralle

Kohutun suurmoskeijahankkeen käsittely alkaa kuukauden kuluessa. Moskeijaa hallinnoivan säätiön perustaminen jäi kesken.

”Valmistelu on loppusuoralla: kaikki materiaali on suurin piirtein kasassa ja ministeriöistä on saatu lausunnot”, sanoo Helsingin tonttiosaston osastojohtaja Sami Haapanen.

Lausunnot on saatu sisäministeriöltä, ulkoministeriöltä sekä opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriöltä.

Haapaniemen mukaan tonttivaraus tulee käsittelyyn kuukauden sisällä.

Sörnäisiin suunniteltu hanke on herättänyt suurta kohua. Lähes 20 000 neliön suuruinen kokonaisuus pitää sisällään moskeijan ja kulttuurikeskuksen sekä liikuntatiloja.

Käytännössä hanke etenee näin: ensin tonttiosasto joko suosittaa tai ei suosita tonttivarauksen tekemistä. Sen jälkeen asia siirtyy kaupunkiympäristölautakuntaan ja lopulta kaupunginhallitukseen.

”Kaupunginhallitus voi päättää asiasta tahtonsa mukaan”, sanoo Haapanen.

Mikäli kaupunginhallitus näyttäisi hankkeelle vihreää valoa, päätyisi moskeija vielä kaupunginvaltuustoon, sillä moskeijan rakentaminen edellyttää asemankaavan muutosta.

Hankkeella on kaupunginhallituksessa vain vähän kannatusta. Eniten mietityttää moskeijan rahoitus, joka on tarkoitus kerätä muslimimaista Bahrainin johdolla.

Tarvittaessa kaupunginhallitus äänestää hankkeesta. Hankkeelle ei juuri löydy kannatusta kaupunginhallituksesta.

Kokoomuksella on viisi paikkaa kaupunginhallituksessa, vihreillä neljä, demareilla ja vasemmistoliitolla kaksi, RKP:llä ja perussuomalaisilla yksi. Kokoomuslainen pormestari Jan Vapaavuori vastustaa hanketta jyrkästi ja monet muutkin kokoomuslaiset suhtautuvat siihen epäillen. DemarienNasima Razmyar ja vihreiden Otso Kivekäs suhtautuvat hekin kriittisesti hankkeeseen. Vasemmistoliiton Paavo Arhinmäki puolestaan on ilmoittanut suhtautuvansa kriittisesti Bahrainista tulevaan rahoitukseen.

Hanketta on ajanut joukko helsinkiläisiä muslimeja, kuten järjestöaktiiviPia Jardi, hänen miehensä Abdessalam Jardi sekä Kampissa toimivan Suomen islamilaisen yhdyskunnan imaami Anais Hajar. Lisäksi hankkeessa on ollut mukana entinen suurlähettiläs Ilari Rantakari.

Joulukuussa 2015 hankkeen puuhamiehet jättivät Patentti- ja rekisterihallitukseen hakemuksen Oasis -nimisen säätiön perustamisesta. Säätiön on tarkoitus pyörittää moskeijakokonaisuutta.

Patentti- ja rekisterihallituksen mukaan säätiön perustaminen jäi kesken, eli hakemuksessa olleita puutteita ei olla vielä korjattu.

Aquilifer

Kenraali

Paljonko vetoa että se suurmoskeija vielä rakennetaan?

Kaikki tietävät mistä raha siihen tulee, mitä ongelmia se tuo, osapuolet valehtelevat sen tarkoitusperistä, se tulee lisäämään jännitteitä islamin eri suuntausten välillä, siellä saarnataan ihan jotain muuta kuin rauhansanomaa, se tulee kuitenkin maksamaan yhteiskunnalle isoja rahoja ja siitä tulee iso vaikuttaja jihadismin leviämiseen tännekin.

Mutta silti se pitää rakentaa, koska rasismi ja hölmölä.

Kaikki tietävät mistä raha siihen tulee, mitä ongelmia se tuo, osapuolet valehtelevat sen tarkoitusperistä, se tulee lisäämään jännitteitä islamin eri suuntausten välillä, siellä saarnataan ihan jotain muuta kuin rauhansanomaa, se tulee kuitenkin maksamaan yhteiskunnalle isoja rahoja ja siitä tulee iso vaikuttaja jihadismin leviämiseen tännekin.

Mutta silti se pitää rakentaa, koska rasismi ja hölmölä.

Paljonko vetoa että se suurmoskeija vielä rakennetaan?

Kaikki tietävät mistä raha siihen tulee, mitä ongelmia se tuo, osapuolet valehtelevat sen tarkoitusperistä, se tulee lisäämään jännitteitä islamin eri suuntausten välillä, siellä saarnataan ihan jotain muuta kuin rauhansanomaa, se tulee kuitenkin maksamaan yhteiskunnalle isoja rahoja ja siitä tulee iso vaikuttaja jihadismin leviämiseen tännekin.

Mutta silti se pitää rakentaa, koska rasismi ja hölmölä.

Tätä mä vähän pelkään kanssa. Että ei uskalleta sanoa ei, vaan mieluummin lyödään kirveellä omaan jalkaan. Tähän tavallaan edellisessä kommentissani viittasinkin.

Kaikuja EU:n ytimestä, Brysselistä...

https://www.washingtonpost.com/worl...97043e57a22_story.html?utm_term=.aa29e8dc687fThe mosque is Belgium’s biggest. Officials say it’s a hotbed for extremism.

BRUSSELS — The Grand Mosque of Brussels is Belgium’s biggest and oldest site of Muslim worship. Officials in Belgium say it is also a hotbed for Saudi-backed Islamist extremism.

Now the Parliament wants the country’s leaders to take over the sprawling complex that is just steps from the gleaming core of the European Union. It is the latest attempt to tighten security after radicalized Belgians emerged at the heart of terrorist attacks in Paris and Brussels in the past three years.

The sudden move against the mosque underscores the challenge for Western European leaders seeking to embrace what they call a “European Islam” that endorses pluralistic values. For too long, many officials say, they have stood by as imams preaching the ultraconservative interpretation of Islam favored by clerics in Saudi Arabia and Qatar have worked among their populations, encouraging frustrated descendants of North African immigrants to wall themselves off from mainstream society.

But the crackdown on the mosque puts Belgian policymakers in the unusual position of picking and choosing among strains of Islam in the name of protecting freedom of religion and democracy. The dilemma grew more pressing after Europe was struck repeatedly by Islamic State-inspired terrorist attacks, often perpetrated by disgruntled citizens born inside the countries they have targeted.

[Belgian woman killed in New York terrorist attack was ‘the most beautiful mom’]

The mosque’s leaders “are trying to live in their splendid isolation with a radical point of view, and their aim is not to integrate into our society. And that is a big problem,” said Servais Verherstraeten, one of the leaders of a Belgian parliamentary commission that recommended last month that the government break the Saudi government’s 99-year, rent-free lease on the mosque. The lease was handed to Saudi King Faisal in 1969 as a goodwill gesture by Belgian King Baudouin.

“We want in Belgium an Islam practiced by people who respect our constitution, who want to integrate into our country,” Verherstraeten said. “There is the perception that there is something to hide in the most important mosque in the country.”

Leaders of the mosque and community center, which is run by the Mecca-based World Muslim League, deny that they espouse a conservative vision of Islam and say that they are working to improve openness.

“I don’t see any contradiction between what we’re trying to do and European Islam,” said Tamer Abou El Saod, executive director of the Islamic and Cultural Center of Belgium, which oversees the mosque.

Abou El Saod, a polyglot Swedish businessman, swooped in to run the center at the end of May after his predecessor upset the parliamentary commission with halting testimony at a hearing. Several lawmakers publicly questioned what he was covering up. That former director was a replacement in 2012 for a director who was quietly asked to leave Belgium after authorities said he advocated radical ideology.

“We can admit that we had some internal management issues,” said Abou El Saod, who described himself as someone who was sent in to fix problems. “This place has maybe not been communicating enough in Belgium.”

“An imam who talks to people here has to be different from one in Oman,” he said in an interview in his office at the mosque, where photographs of Mecca adorn the walls along with blurry likenesses of the old Belgian and Saudi kings.

The Saudi lease is unusual but not unique. The Saudi government operates an Islamic school near Washington Dulles International Airport, for example, and it helps fund mosques and imams around the world.

Belgian counterterrorism officials acknowledge that a move against the crowded mosque will do little to stem radicalization that more often comes over the Internet or on the street, and they say they have no evidence that its imams have advocated violence or lawbreaking.

But they also say they were mistaken to adopt a live-and-let-live attitude to the squat, plain concrete mosque tucked in the corner of central Brussels’s Cinquantenaire Park, across the street from apartment buildings and the boxy office block that holds the E.U. diplomatic headquarters. On Fridays, worshipers spill from prayers and mix with joggers and suited bureaucrats strolling along the park’s manicured paths.

In the half-century since the Saudi government took over the site, Belgian authorities say, the mosque has espoused the hard-line interpretation of Islam favored in the conservative Persian Gulf monarchy. That has undermined an effort originally intended to help serve Belgium’s then-growing Moroccan and Turkish guest-worker communities, they say. The center is Belgium’s main hub for conversions to Islam, and its religious and Arabic-language schools teach 850 pupils.

The Belgian move came at the same time the newly named Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, announced in Riyadh that he wanted to fight extremist interpretations of Islam.

[Attempted Brussels attack ‘could have been far worse,’ Belgian prime minister says]

Belgium’s migration agency is also trying to expel the mosque’s top imam, an Egyptian cleric who is accused of preaching an ultraconservative vision of Islam to his flock during his 13 years in Belgium.

The reassessment came after the March 2016 attacks on the Brussels airport and subway that killed 32. Those attacks were led by Belgians with Moroccan roots. They are not believed to have had ties to the mosque, but the violence disturbed Belgian security services and led to a broad rethinking of their strategy.

Although the Saudi government is the leading funder of the World Muslim League, which operates the mosque, the group is independent and more than 50 other Muslim nations contribute to its operations. The league’s top leader, Secretary General Muhammad Al-Issa, was Saudi justice minister until last year.

The mosque’s longtime imam, Abdelhadi Sewif, said that he is mystified that the Belgian state is attempting to expel him and his family by refusing to renew their residence permits. He is appealing the decision, and he joked that his trim beard was too short and his floor-scraping robe too long to satisfy radicals.

In an interview, Sewif said that he had always advocated a moderate form of Islam and that he never called Muslims to cut themselves off from mainstream society, as Belgian authorities have accused him of doing. He said he was searching his past words for what had made him a target. Authorities have not let him see the evidence against him.

“When I tell Muslims that Muslims love their Muslim brothers and have to help each other, does this then mean you should hate the rest?” he said. “I have always fought violence and spoken up against it. . . . I have always preached about forgiveness in Islam and in behavior.”

[Attacker in Nice is said to have radicalized ‘very rapidly’]

But despite the mosque’s protests, the Belgian government appears ready to break the lease and boot out its imams.

Sewif “is a dangerous man to the national security of our country,” Theo Francken, the Belgian state secretary for asylum and migration and an anti-immigration hard-liner, told the RTBF broadcaster.

Francken declined a request for an interview. After this article was published, he disputed the characterization that he is “an anti-immigration hardliner,” saying on Twitter that “I am not ANTI-immigration, I am in favor of a DIFFERENT, clear and firm migration policy and 100% against a laissez-faire, laissez-passer migration policy of ambiguity and arbitrariness. And I work in that direction with the support of the vast majority of our population.”

Lawmakers said that they were taken aback by the testimony of the then-director and one of Sewif’s imam colleagues earlier this year.

“The hearing was astonishing,” said Gilles Vanden Burre, a member of the parliamentary commission. “It was not an open and progressive and tolerant Islam.”

Inside Parliament, the two mosque officials outlined a vision of starkly regressive gender roles and a prickly attitude toward mainstream Belgian society, Vanden Burre said.

“It’s not objectively proved that they have a link with jihad or radicalization. But all those processes to show their goodwill to integrate, they never did,” he said.

Segregation leads to alienation, Belgian security officials said. And that can make people more receptive to Islamist militant messages.

Officials said there was no recent shift at the mosque that set off alarm bells to cause the new approach. Instead, several said, it was Belgium that had changed. Policymakers have hardened their attitudes in a challenging era of terrorism.

“Many of the guys say they are not violent, but then they actually do preach hatred,” said a security official who is familiar with the investigation and spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal intelligence matters. “The issue that we have in Belgium is that people are teaching an Islam that is incompatible with Belgium or Europe.”

Editor's note: After publication, this article was updated to include comment from Belgian State Secretary for Asylum and Migration Theo Francken.

Annabell Van den Berghe contributed to this report.

#vihapuhetta lopussa..

https://www.verkkouutiset.fi/muslimit-hairitsevat-suomessa-kristityiksi-kaantyneita/Muslimit häiritsevät kristityiksi kääntyneitä

JUHA-PEKKA TIKKA | 21.11.2017 | 00:01- päivitetty 21.11.2017 | 00:13

Uutuuskirjassa kerrotaan, miten Suomen ex-muslimeita painostetaan rankasti heidän yhteisöissään.

Toimittaja Mari Turusen kirjaan Kääntyneet on haastateltu 31 entistä muslimia Suomessa ja otettu yhteyttä 165 luterilaisen seurakunnan kirkkoherraan. Syksyllä 2015 Suomeen tuli aalto turvapaikanhakijoita, joista moni on kääntynyt kristityksi.

Kirjan tiedotteen mukaan monet heistä ovat joutuneet täällä vakavan häirinnän kohteeksi.

Evankelisluterilainen Kansanlähetyksen julkaiseman kirjan 31 haastatellusta 27 sanoo joutuneensa vaikeuksiin kristinuskoon kääntymisen vuoksi. Yleisintä on eristäminen, puhumattomuus, uhkailu ja elämän hankaloittaminen.

Viisi vastaajista oli kokenut väkivaltaa. Heitä on hakattu, pahoinpidelty ja potkittu.

– Täällä uskonnonvapauden mallimaassa on ihmisryhmä, joka joutuu kärsimään vakavaa häirintää uskonsa vuoksi, Mari Turunen toteaa.

Anonyymit ex-muslimit kertovat muun muassa seuraavaa:

”Kun kerroin äidilleni uskostani, hän toivoi, että olisin mieluummin kuollut kotimaassani kuin kääntynyt.”

”Meidät on eristetty, meitä vältellään, eivätkä muut lapset saa leikkiä lastemme kanssa.”

”Kofer tarkoittaa luopiota. Monissa maissa hänet voi rauhassa tappaa ilman seuraamuksia. Murhaaja pääsee paratiisiin, kuten Koraani lupaa.”

”’Jos kerrot jollekin, me tapamme sinut’, he huusivat mennessään. Minäkin poistuin nopeasti paikalta. Palattuani vastaanottokeskukseen muslimihuonetoverini naureskeli minulle ja sanoi: ’Sait mitä ansaitset.'”

”Pelko oli jatkuvaa. Vastaanottokeskuksessa kävi imaameja, jotka alkoivat uhkailla omaisiani kotimaassa ja myös omaa henkeäni.”

”Tytärtemme eteen on syljetty, kun he eivät peitä päätään.”

Ex-muslimeiden avioliitot on mitätöity eikä vaimoon saa enää olla yhteydessä.

– On henkistä häirintää, kiusaamista ja haukkumista, joka voi olla niin rajua, että se järkyttää mielenterveyttä. Usein mukana on pelottelua ja uhkailua, joka kohdistuu henkilöön itseensä tai hänen läheisiinsä. Ja sitten on raakaa väkivaltaa, Turunen kirjoittaa.

Kirjassa pastori Timo Keskitalo kirjoittaa, että Suomessa maltillisetkin imaamit myöntävät, että luopiot pitäisi surmata, mutta se ei ole täällä mahdollista. Imaamit miettivätkin, miten soveltaa Koraania, kun eletään vähemmistönä vääräuskoisen lain alla.

– Islamin tavoitteena on, että shariaa voidaan noudattaa siellä, missä asuu muslimeja. Tämä imaamien tavoite on dokumentoitu myös Suomessa jo 90-luvulla, Keskitalo toteaa.

https://www.verkkouutiset.fi/suomessakin-muslimien-sisainen-laki-luopiot-kuin-lainsuojattomia/

Suomessakin sisäinen laki – muslimiyhteisö ratkaisee luopioiden kohtalon

JUHA-PEKKA TIKKA | 21.11.2017 | 00:00- päivitetty 21.11.2017 | 00:04

Uutuuskirjan mukaan islamin hylänneitä kohdellaan myös meillä kuin lainsuojattomia.

Toimittaja Mari Turusen uudessa Kääntyneet-kirjassa (SEKL) Suomen Islamilaisen Yhdyskunnan imaami Anas Hajjar myöntää, että puolison käännyttyä islamista kristinuskoon avioero astuu voimaan heti. Islamin jättänyt ei peri eikä häntä peritä.

Islamista ei katsota olevan mahdollista luopua. Shariaa rikoslaissaan noudattavissa maissa siitä rangaistaan kuolemalla.

Turusen mukaan Anas Hajjar katsoo vastauksensa perusteella, että islamin jättäneen kohtelu kuuluu muslimiyhteisön johtajan päätäntävaltaan. Hajjar ei tuominnut Turusen mainitsemia muslimiyhteisön toimesta annettuja tappouhkauksia tai hylkäämisiä.

Anas Hajjar antoi vastaukset kirjan kysymyksiin viikon kuluttua kirjallisesti ja vaati niiden julkaisemista kokonaisuutena.

Mari Turusen mukaan ”hänen kommenttinsa vahvistavat haastateltujen kokemukset, ja samalla hän tulee paljastaneeksi, että Suomessa toimii jo yhteisön sisäinen laki, kun muslimiyhteisö ratkaisee islamin hylänneen kohtalon”.

– Vähintään hän menettää aviopuolisonsa ja perimysoikeutensa.Tällaisesta ajatusmaailmasta nousee monen vastaajan kokemus, että he ovat kuin lainsuojattomia. Silloinkin, kun he eivät pelkää henkensä menettämistä, monia kohdellaan tavoilla, jotka ovat julmia, kirjassa todetaan.

– Se, mikä on ollut tavanomaista lähtömaassa, voi kuitenkin täyttää Suomessa rikoksen tunnusmerkit. Nämä törmäykset ovat vakavia.

Suomessa käsillä oleva tilanne on kirjan mukaan Ruotsin ja Saksan tavoin poikkeuksellinen, kun sadat muslimit ovat kääntyneet kristityiksi.

– Samalla ihmisoikeudeksi ymmärretty oikeus vaihtaa uskontoa törmää islamin uskontulkintaan. Tämä käy ilmi Open Doors -järjestön vuonna 2016 tekemässä selvityksessä Saksassa tehdyistä hyökkäyksistä kristityksi kääntyneitä turvapaikanhakijoita kohtaan.

– Suomen Islamilaisen Yhdyskunnan imaamin, Anas Hajjarin, kuvaus siitä, kuinka islamin hylännyttä yhteisössä kohdellaan, osoittaa, että Suomessakin islamin hylännyt joutuu yhteisössään haavoittuvaa asemaan. Tämä on huolestuttavaa.

Rauhantekijä

Greatest Leader

Kuten aikaisemminkin todettu; parhaiten suomalainen tähtää ja osuu omaan jalkaansa.Mutta silti se pitää rakentaa, koska rasismi ja hölmölä.

Siitä tässäkin on kyse. Poliitikkojen ei pidä ohittaa kansan tahtoa tai seuraa "merkelit".

https://www.hs.fi/kaupunki/art-2000...-other&share=0465e842c61d4983af1b6c39593e14a3Päätös Helsingin suurmoskeijasta siirtyy epämääräiseen tulevaisuuteen, hakijat perääntyivät – ”Tässä on ollut erilaista päivitystä ja muuta”

Kaupunkiympäristölautakunnasta ilmoitettiin keskiviikkona, että aiheen käsittely viivästyy hakijoista johtuvista syistä. Suurmoskeijahankkeen taustalla olevat hakijat sanovat viivästyksen johtuvan poliitikoista ja kaupungin viivyttelystä.

Helsinkiin suunnitellun suurmoskeijan ja monitoimikeskuksen tonttivarauksen piti vihdoin siirtyä poliittiseen päätöksentekoon perjantaina, mutta nyt näin ei näytä käyvän.

Alun perin oli ilmoitettu, että tonttivaraus nousee kaupunkiympäristölautakunnan esityslistalle 24. marraskuuta, ja lautakunta käsittelee asiaa ensi viikolla. Todennäköisimpänä sijaintina moskeijalle on pidetty Helsingin Hanasaarta.

Kaupunkiympäristölautakunnasta kerrottiin kuitenkin keskiviikkona, että aiheen käsittely viivästyy hakijoista johtuvista syistä. Suurmoskeijahankkeen taustalla olevat hakijat sanovat viivästyksen johtuvan poliitikoista ja kaupungin viivyttelystä.

Suurmoskeija- ja monitoimikeskushankkeen ydinryhmäläiset Pia Jardi ja Ilari Rantakari myöntävät, että hanketta ei päästä käsittelemään vielä ensi viikolla. On epäselvää, kuinka kauas tulevaisuuteen sen käsittely siirtyy.

”En osaa tarkalleen sanoa. Tässä on ollut erilaista päivitystä ja muuta. Tämä on vielä sillä tavalla kesken, että ehkä kaupunki on katsonut, että käsittelyä pitää lykätä. Kaupungin ja muiden tahojen kanssa on tullut paljon viivästyksiä matkan varrella”, Rantakari sanoo.

Rantakari korostaa, että hänen vastuualuettaan on hankkeessa nimenomaan suunniteltu koulutus- ja dialogikeskus, ei itse moskeija. Rantakari harmittelee ylipäätään sitä, että uutisointi keskittyy vain suurmoskeijaan, vaikka sen osuus olisi hänen mukaansa suunnitellusta kokonaisuudesta vähäinen.

”Moskeijan kokoluokka olisi noin 3 000 neliötä ja muun osan noin 13 000 neliötä. Tässä on kyse nimenomaan palvelu-, koulutus- ja konferenssikeskuksesta.”

”Muu osa” kattaa Rantakarin mukaan vaikka mitä: liikunta- ja urheilutiloja, vanhus-, nuoriso- ja varhaiskasvatuksen tiloja, ateriapalvelun, sosiaalipalveluita, näyttelykeskuksen ja kirjaston.

Alku-, investointi- ja käyttörahoitus tulisi hänen mukaansa Bahrainin kuningaskunnalta. Tavoitteena on, että lopulta suomalainen muslimiyhteisö ja esimerkiksi koulutuksista ja muista palveluista saadut varat toisivat sisään kotimaista rahaa.

Liittyykö nyt otettu aikalisä jollain tavalla suurmoskeija- ja monitoimikeskus hankkeen rahoituksesta käytyyn keskusteluun?

”Ei ehkä sinänsä, en osaa sanoa sen tarkemmin. Olemme tietysti sopineet, että rahoituksesta tehdään yksityiskohtaiset suunnitelmat.”

Onko sellaiset jo olemassa?

”Alkuvaiheen rahoitussuunnitelma on jo olemassa, mukaan luettuna arkkitehtuurikilpailu. Kaupunki toivoo kuitenkin vielä lisäselvityksiä.”

Mistä rahat tulevat tarkalleen?

”Ihan normaalisti, Bahrainin kuningaskunnalta. Olemme tähän mennessä saaneet ne suoritukset, joista on sovittu. Rahat tulevat sitä mukaa, kun niitä tarvitaan. En mene tähän nyt sen yksityiskohtaisemmin.”

Kuka on yhteyshenkilönne Bahrainin kuningaskunnasta?

”Kuningaskunnan ja kuninkaan ministeriö.”

Pia Jardin mukaan syynä viivästyneeseen aikatauluun ovat poliitikot, joiden kanssa ei ole saatu sovittua tapaamisia. Jardin ja Rantakarin toiveena on, että poliitikkojen ja kaupunkiympäristölautakunnan jäsenten kanssa keskusteltaisiin epävirallisesti ennen virallisen poliittisen prosessin alkamista.

Jardi ei kysyttäessä täsmennä, keiden poliitikkojen kanssa hän on yrittänyt järjestää tapaamista.

Helsingin kaupunkiympäristölautakunnan varapuheenjohtaja Risto Rautava sanoo, ettei ainakaan häneen ole oltu minkäänlaisessa yhteydessä suurmoskeija- monitoimikeskushankkeeseen liittyen.

”Tämä on aivan pomminvarma juttu, minuun ei ole oltu yhteydessä kertaakaan viimeisen puolen vuoden aikana. Yhteystietoni ovat kaikkialla, joten minut on helppo saada kiinni.”

Rautava ihmettelee sitä, miksi Ilari Rantakari haluaa korostaa moskeijan ja monitoimikeskuksen erillisyyttä.

”Molemmille haetaan samaa tonttia, ja rahoitus tulee samasta paikasta.”

HS on aiemmin valottanut suurmoskeijahankkeen taustoja.

Sopivaa paikkaa moskeijalle on haettu vuodesta 2015, jolloin Pia Jardi, Abdessalam Jardi ja Ilari Rantakari jättivät varaushakemuksen kaupungille. Nyt hanketta vetää sitä varten perustettu Oasis-säätiö, jonka rekisteröinti on edelleen vireillä. Suurmoskeijan tontti haluttaisiin Rantakarin mukaan saada Oasis-säätiön nimiin.

Erityisesti moskeijahankkeen rahoituslähteet ovat herättäneet keskustelua. Arviolta noin 110–140 miljoonaa euroa maksavan hankkeen alkurahoitus olisi tulossa Persianlahden Bahrainista, jonka valtauskonto on konservatiivinen islam.

Sekä suojelupoliisi että sisäministeriö ovat selvittäneet rahoituslähteiden vaikutusta islamiin, jota suurmoskeijassa mahdollisesti harjoitettaisiin. Hankkeen kokonaisrahoitus on toistaiseksi ollut epäselvä.

Helsingin kaupunki on pyytänyt hankkeesta lausunnot opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriöltä, ulkoministeriöltä sekä täydentävän lausunnon sisäministeriöstä.

Sisäministeriön lausunnossa poliisijohtaja Marko Viitanen ja kehittämispäällikkö Tarja Mankkinen korostavat, että Suomen viranomaistenkin on usein hyvin vaikea selvittää ulkomaisia rahoituslähteitä.

Lopullisesti suurmoskeijan rakentamisen edellytyksistä päättää Helsingin kaupunginvaltuusto.

= palvelukeskus muslimeille, jotta he pysyvät ja asioivat omissa tiloissaan suomalaisen yhteiskunnan ja kantaväestön ulkopuolella näin estäen integroitumista, länsimaistumista ja kärjistäen muslimit ja muut -asetelman. Jotta muslimit uivat muslimiuimahallissa, käyvät muslimipäiväkodissa, ostavat ruokansa A(llah)-Marketista, juovat päiväkahvinsa muiden muslimien ympäröimänä, asioivat muslimikirjastossa, käyvät muslimikansalaisopistossa opiskelemassa uusia taitoja, laittavat hiuksensa muslimikampaajalla, käyvät muslimipunttisalilla...

Ja tämän kaiken perusteleva argumentti on "jotta nuoret muslimit voivat tuntea kuuluvansa suomalaiseen yhteiskuntaan".

Touche.

Rantakari korostaa, että hänen vastuualuettaan on hankkeessa nimenomaan suunniteltu koulutus- ja dialogikeskus, ei itse moskeija. Rantakari harmittelee ylipäätään sitä, että uutisointi keskittyy vain suurmoskeijaan, vaikka sen osuus olisi hänen mukaansa suunnitellusta kokonaisuudesta vähäinen.

”Moskeijan kokoluokka olisi noin 3 000 neliötä ja muun osan noin 13 000 neliötä. Tässä on kyse nimenomaan palvelu-, koulutus- ja konferenssikeskuksesta.”

”Muu osa” kattaa Rantakarin mukaan vaikka mitä: liikunta- ja urheilutiloja, vanhus-, nuoriso- ja varhaiskasvatuksen tiloja, ateriapalvelun, sosiaalipalveluita, näyttelykeskuksen ja kirjaston.

https://www.hs.fi/kaupunki/art-2000...-other&share=0465e842c61d4983af1b6c39593e14a3

Pihatonttu

Respected Leader

"Moskeijan kokoluokka olisi noin 3000 neliötä ja asevarikon, harjoittelusalien + taistelunjohtokeskuksen noin 13 000 neliötä. Harmi, että uutisointi keskittyy pelkkään moskeijaan."

Taisin mainita "paperittomien" terveyspalveluja koskevassa keskustelussa viimeksi, että kun se meni Helsingissä läpi, niin sama tulee käymään suurmoskeija hankkeellekin...

https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-9966033Helsingin suurmoskeija lähempänä kuin ennen – arkkitehtuurikilpailu jo puolen vuoden sisällä?

Suurmoskeijan arkkitehtuurikilpailua esitetään käynnistettävän. Rahoitukselle esitetään myös tiukkoja ehtoja.

Helsinki

Suurmoskeijan arkkitehtuurikilpailua esitetään käynnistettäväksi. Asiasta keskustellaan ensi viikolla Helsingin kaupunkiympäristön toimialan lautakunnassa.

Helsingin virkamiesten valmistelema esitys on moskeijalle kaikkiaan myönteinen, mutta tiukkoja ehtoja on paljon. Tiukimmat säännöt koskevat moskeijan rahoitusta. Rahoitus on aiheuttanut keskustelua jo aiemminkin. Toimialajohtaja Mikko Aho sanoo, että rahoituksen seuraamiseksi Helsinki tarvitsee myös apua.

Rahoituksen tulee esityksen mukaan olla läpinäkyvää ja avointa, eikä se saa aiheuttaa riippuvuussuhteita. Rahoituksen tulisi olla selvillä jo kolmen kuukauden kuluttua siitä, kun päätös suunnitteluvarauksen tekemisestä olisi tehty.

Muita ehtoja on muun muassa se, että suurmoskeijaa vetämään pitäisi syntyä säätiö, joka alkaisi vetää hanketta.

Lopullisen päätöksen hankkeen etenemisestä tekee Helsingin kaupunginhallitus vielä tämän vuoden puolella.

Jos kaupunginhallituksen päätös on myönteinen, arkkitehtuurikilpailu suurmoskeijasta voidaan aloittaa. Kilpailu pitää esityksen mukaan julkistaa jo kuuden kuukauden kuluttua puoltavasta päätöksestä. Suunnitteluvarauksen ja arkkitehtuurikilpailun aloittaminen ei mene Helsingin valtuuston päätettäväksi.