Late in the summer of 2014, surveillance footage of Syria’s Tabqa air base showed up on YouTube. That it was taken by ISIS forces is unremarkable. That it was shot with a DJI Phantom FC40—a popular consumer drone at the time, the kind you might have found under the Christmas tree—certainly was.

In the intervening year and a half, small quadcopter drones have become even more affordable and more broadly available. That’s

enabled them to find all sorts of positive new purposes, from agriculture to inspecting cell towers. That increased accessibility, though, has also inspired a proportionate amount of concern about the misuse of drones. A

new report (PDF) from the non-profit group Open Briefing lays bare just how far the threat from hobbyist drones has evolved, and how seriously we should take it.

The Threat Abroad

Let’s start with a healthy dose of perspective. Consumer drones aren’t currently a major part of the ISIS arsenal. There aren’t roaming packs of DJI Phantoms or Parrot Bebops terrorizing the streets of Ramadi. Even that first public incident, the 2014 Tabqa footage, “appeared to be for propaganda purposes only,” according to the Open Briefing report.

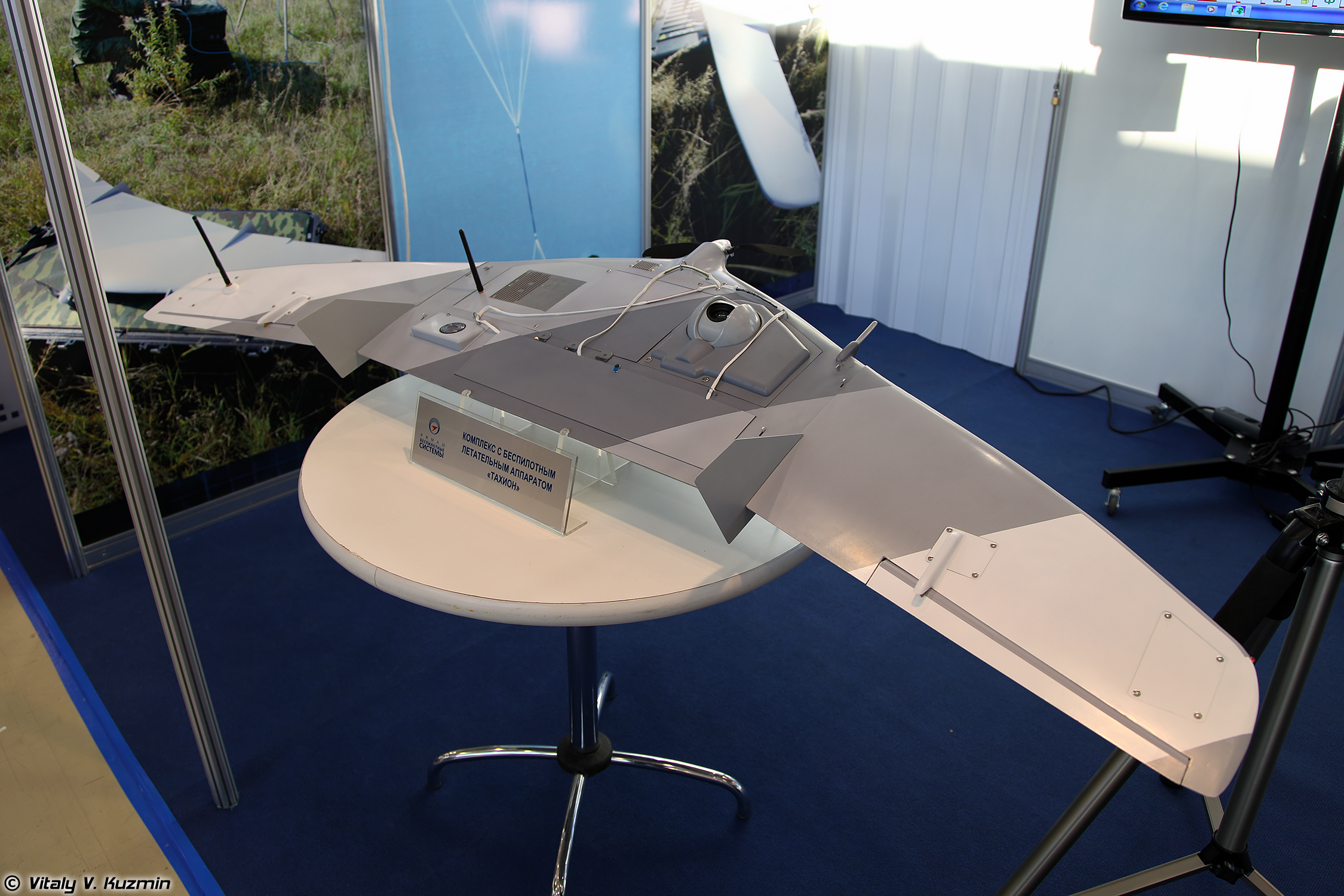

That perspective need also include, though, the swift evolution of the uses ISIS forces have found for these quadcopters. “The range of scenarios that threat groups have or are likely to use drone in can be broadly divided into two types of threat: intelligence gathering or attack,” says Chris Abbott, founder and executive director of Open Briefing.

His group’s report details multiple instances of the former. ISIS used a hobbyist UAV in April of last year to help coordinate its attack on Iraq’s Baiji oil refinery complex. The following month, Kurdish forces shot down an ISIS drone that had been monitoring their positions. And these are just the times they’ve been caught.

Reports of weaponized drones are more muddled, though one unconfirmed report claims that Kurdish forces recently shot down a small drone—the kind you can make at home from a mail-order kit— carrying explosives. Most consumer drones can’t currently carry heavy enough payloads to do very significant harm, but that doesn’t mean they’re ineffective.

“It’s a really crude method of packing a drone with explosives, and using it like a flying IED,” says Colin Clarke, associate political scientist at the RAND Corporation. “It’s more of a psychological threat than anything. It’s probably far more effective to lob artillery, or mortars, or RPGs toward the front line. But if all of a sudden you’ve got this drone flying forth, it strikes fear in the heart of the enemy.”

Clarke and Abbott agree that ISIS primarily leans on drones for intelligence gathering at the moment, and even that effort could be charitably described as piecemeal. Both also, though, see the potential for much more harmful pursuits ahead.

“These groups are highly adaptable. They’re able to learn from each other and their own mistakes,” says Clarke. “They’re going to get better at this stuff. They’re going to perfect it.”

However steep that learning curve turns out to be, it likely ends not in Syria or Iraq, but in one of the Western nations ISIS has clear intent to attack.

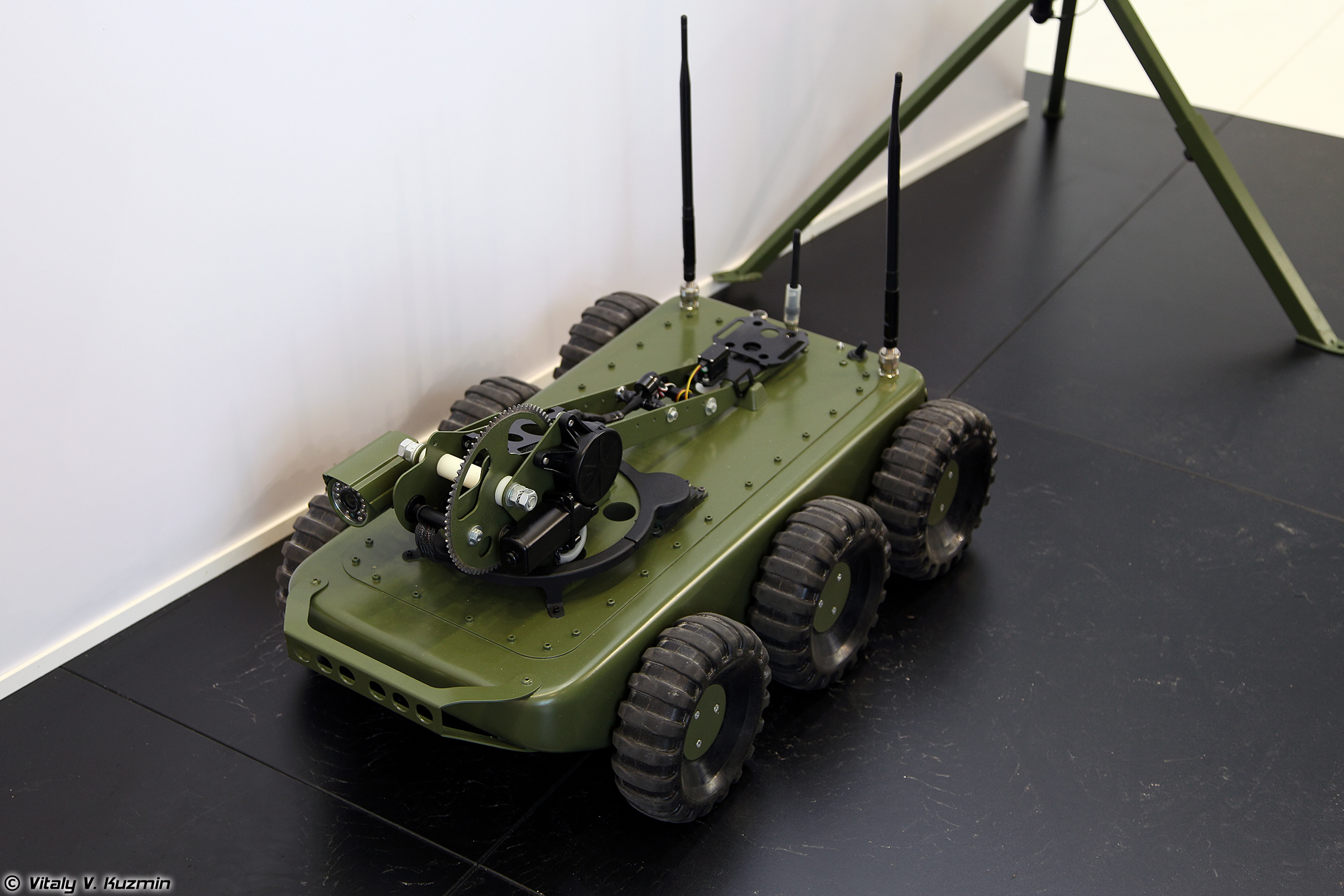

“The failure of Islamic State to successfully use drones for attack in Iraq and Syria shows that the method of attack has some difficulties,” says Abbott. “However, Iraq and Syria provides the group with the testing ground to perfect the delivery of IEDs by unmanned aerial or ground vehicles. Once perfected, multiple sources have suggested that the group is looking to use drone swarms to overwhelm any defenses and deliver spectacular attacks.”

The idea of a coordinated drone attack rightly sounds terrifying. (These are, after all, terrorists). For that matter, so does a precisely placed lone wolf quadcopter. How likely that type of attack is to take place outside of the Middle East theater, though, remains a question of some debate.