"It will work while the war is going on." Who sells Starlink "for SVO"

3 hour(s) ago

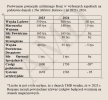

The Russian military can actually use the Starlink satellite communication system at the front due to the lack of control on the part of SpaceX over the personal data of clients during registration and the technical impossibility of limiting access to the Internet to only one of the warring parties, Radio Liberty found out after talking with military personnel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and experts and sellers of "Starlinks for SVO". Starlink supplies to Russia are carried out by dozens of companies that simultaneously import into the Russian Federation household goods of brands that have left Russia - such as cars or washing machines.

On February 8, popular Ukrainian blogger and volunteer

Sergei Sternenko published information that the Russian army began to increasingly use Starlink satellite systems at the front, developed by SpaceX, which are officially not available to users from Russia and do not work within the country. Before this, in the vast majority of cases they were used only by the Ukrainian army.

Sternenko said that the systems themselves are supplied to the Russian army from the United Arab Emirates with accounts pre-activated outside Russia, so they also work in the occupied territories of Ukraine. At the same time, the Starlink website now

says that their terminals work only in part of the Russian-controlled regions of Ukraine. “We will try to convey the collected evidence at the highest level,” Sternenko added.

A few days later, the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense announced that Russia was increasing the use of Starlink terminals at the front. Department representative

Andrei Yusov said that cases of use of Starlink systems by Russians have been recorded and this phenomenon is becoming widespread. Later, the Main Intelligence Directorate published a radio intercept of a conversation allegedly between two soldiers of the Russian 83rd Air Assault Brigade. In it, one of the servicemen reports on the installation of this system at the position. The 83rd brigade is fighting in the area of Kleshcheevka and Andreevka near Bakhmut. On February 13, Ukrainian intelligence announced that it had intercepted another

conversation between Russian military personnel, in which they discussed the purchase of Starlink systems and components for them from Arab countries for 200 thousand rubles. “The Arabs bring everything: wires, Wi-Fi router,” says one of them. Radio Liberty cannot promptly verify the authenticity of these recordings.

Starlink terminals at Russian positions have already been captured on video shot by Ukrainian drones. Photos with boxes, which allegedly contain unpacked Starlinks, are also published by the Russian military themselves.

SpaceX said it does not do business with the Russian authorities or the Russian army. They noted that Starlink satellite systems are inactive in both Russia and the UAE and are not supplied to these countries.

“If SpaceX receives information that Starlink terminals are being used by sanctioned or unauthorized parties, we will investigate and take action to deactivate the terminals,” the company

said in a statement. SpaceX owner

Elon Musk also responded to the accusations. He

stated that the information that Starlink terminals are being sold to Russia is a lie. According to Musk, the company is not aware of systems being sold to Russia indirectly or directly.

Commenting on the statements of the Main Intelligence Directorate, Vladimir Putin’s press secretary

Dmitry Peskov noted that Russia does not purchase the Starlink system through official channels. “This is not a certified system with us, therefore, it cannot be supplied and is not supplied officially. Accordingly, we cannot use it officially in any way. Here, perhaps, we should not intrude into the discussions between the Kyiv regime and the entrepreneur Musk,” said Peskov.

"Starlink stretched Bakhmut's defenses"

Musk, who now advocates reducing military aid to Ukraine, said during a recent

call with Republican senators that his companies have "probably done more to undermine Russia than anyone else." Indeed, the significance of the Starlink terminals, which have been supplied to the Ukrainian military since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion, is very great.

Starlink terminals in the Armed Forces of Ukraine are used on the front line primarily for stable communication between various units, doctors and headquarters. Ukrainian troops are also experimenting with installing Starlink antennas on large attack drones, making them difficult to jam or jam with electronic warfare. But the primary function of the terminals at the front is stable communication. A Ukrainian army serviceman, in a conversation with Radio Liberty, noted that “Starlink greatly stretched the defense of Bakhmut.”

A Ukrainian military man installs an antenna for the Starlink system, Kremennaya, Donetsk region of Ukraine. January 6, 2023

It is indeed practically impossible to jam the terminals using electronic warfare, as noted by two of our interlocutors, servicemen of the Ukrainian army. “There is an opinion that Starlink can be jammed if you are above it in the air, but this has not been confirmed. Just in case, we monitor the correct location of the antennas and additional protection from electronic warfare,” noted one of them.

In some areas of the front, the Russian army has had Starlink for a long time, says another serviceman. Thus, fighters of the Wagner PMC used Starlink during the assault on Bakhmut in January 2023 - they found some systems in positions abandoned by Ukrainian troops, and some, according to Radio Liberty’s interlocutor, were brought from Africa.

Both military officers agree that the massive use of Starlink terminals by the Russian army will not fundamentally change the situation on the front line. “They will have a stable and high-quality connection. There will be an additional load on the network, but this is not critical,” notes a serviceman of the Ukrainian territorial defense.

“It’s a miracle that the Russians didn’t think of this before.”

Independent researcher

Jakub Yanovsky , who collaborated with the Bellingcat and Oryx projects and is well acquainted with the principles of satellite communications, writes on the social network X that one “cell” of Starlink network coverage includes a fairly significant territory and SpaceX can only approximately determine where that one is located or other terminal.

According

to Jakub Yanovsky, in order to avoid Starlink coverage of Russian positions, SpaceX would have to turn off the terminals used by the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

“This is all public information - it’s a miracle that the Russians didn’t think of this sooner. They have good reasons not to use Starlink, but low-level military personnel may not care,” Yanovsky

adds , referring to the theoretical possibility of Ukraine or the United States intercepting data. received by the Russian military via Starlink.

Another solution to the problem could be a “white list” of terminals available to the Ukrainian army - so that no other Starlink terminals work at the front. This, however, will require regular and prompt collection of information from all units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (which do not always receive terminals centrally) - both about the terminals at their disposal and about terminals lost during combat operations.

Magician and fraudulent shops

The lack of official Starlink supplies does not prevent parallel “gray” imports. The American satellite communications system ends up in Russia in the same way as luxury cars and

household appliances from brands that have left the Russian Federation. The intermediaries involved in such deliveries are often small entrepreneurs with experience in network marketing and online trading.

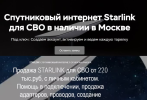

At the request “buy Starlink in Russia” you can find several dozen sites offering delivery and connection of equipment in the Russian Federation: the price range is approximately from 200 000 to 400 000 rubles per device. Basically we are talking about using the system on yachts in the ocean - where there is Starlink coverage. Some projects, for example the website Topmachines.ru, directly offer the supply of an American Internet system “for the SVO.”

The cost of one Starlink set from Topmashin starts at 220 000 rubles (approximately 2200 US dollars), the subscription fee is 100 dollars per month. “With the Internet from Starlink you get complete anonymity, protection from electronic warfare, access to any sites. This model is not tracked, it is safe in the north,” says the website. The user’s personal account is created “in another country,” and the site owners offer to pay for the subscription fee “through us.”

Topmachiny is engaged not only in the supply of Starlink: for them, this is, apparently, a relatively new business. Although the first videos about the sale of an Internet system to Russia appeared on the project’s YouTube channel back in October 2022, a separate channel for them was created only a year later, in October 2023. The main business of the project is the supply of custom-made cars from the UAE to Russia; TopMachines also offers investments and exchange of rubles for Emirati dirhams.

The Topmashin website and the project’s social networks do not indicate a legal entity, only contact numbers and names - Alexey and Victoria (this is typical for all projects offering Starlink in Russia). In one of the few public

reviews left for work with the project, perhaps by its owners, it is stated that Alexey and Victoria are brother and sister, he works in Dubai, she works in the Russian Volgograd.

Using phone numbers and publicly accessible Radio Liberty databases, it was possible to establish that the administrators of Topmashin are indeed brother and sister, Victoria and Alexey Ovchinnikov. They were born in the early 1990s in Germany in the cities where the Western Group of Soviet Forces was stationed, and spent their childhood in Blagoveshchensk. Victoria later lived in the city of Volzhsky in the Volgograd region and in Torzhok in the Tver region. Together with her partner Alexey Svirsky, Victoria Ovchinnikova managed the online clothing store VK-mystery.

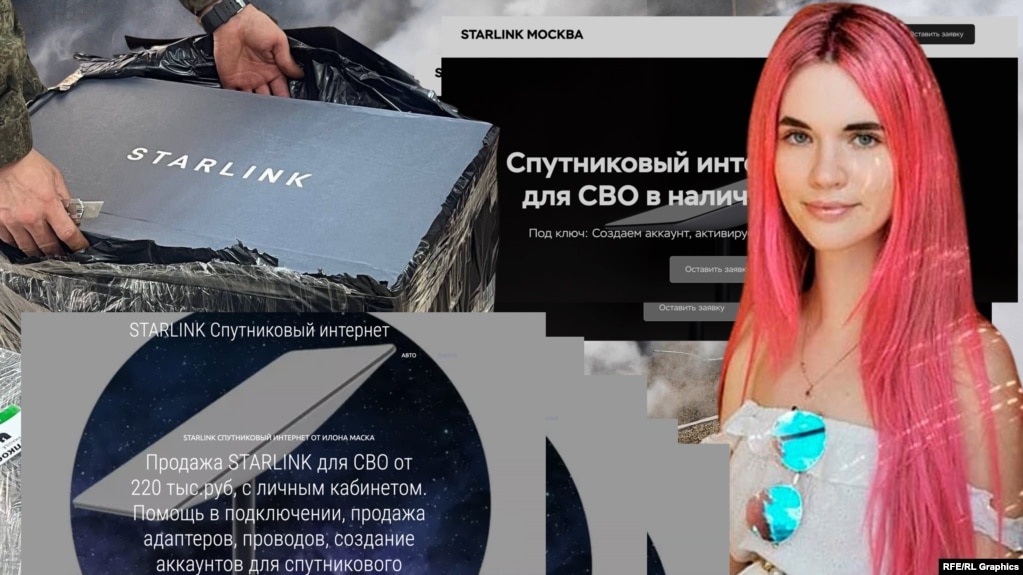

Victoria Ovchinnikova

Users on the Internet left many negative reviews for this store, accusing the project owners of fraud in sending goods and non-return of money - there were hundreds of such cases in

Torzhok ,

Volgograd and

other regions. Alexey Svirsky was convicted of fraud in 2010; in addition to an online clothing store, he was involved in cryptocurrency mining equipment under the UPMiner brand. We were unable to establish whether he is involved in the project to supply Starlink to Russia.

Victoria Ovchinnikova, in addition to the Topmachiny project, owns an operating

online store of magical amulets, offers consultations on Tarot cards, mentoring and

training for “unlocking magical abilities.” Two years ago, she participated in the Miss Notebook Volzhsky 2022 beauty contest and stated in

an interview that her hobby is helping people. “This is both my professional activity and my hobby,” she told Notepad.

Her brother Alexey Ovchinnikov, apparently the second administrator of Topmashin, judging by the content of his telegram subscriptions, really spends a lot of time in the UAE.

In correspondence with RS, a Topmashin representative said that the terminals arrive in Russia “fully ready with an account registered in Poland.” He clarified that the project registers all accounts “in its own name.” “These are all originally our plates, that is, it is not as if an account was registered under someone else,” he added.

"Left European Data"

Another Starlink seller in Moscow explained to Radio Liberty how this works - this project also offers supplies “for SVO.” According to the seller, accounts are registered with random European first and last names and “left European data from the data generator”, since when creating an account in the system, confirmation in the form of a passport is not required. The only important thing is to have a valid bank card from one of the international payment systems - the company is ready to help with this.

Starlink satellite communications kit smuggled into Iran

“We have a one-month warranty on the equipment, it works for everyone, we create an account for Europeans, they are not blocked, we pay with our foreign cards. In the “DPR”, “LPR” and Crimea it will work 100% while the fighting is going on, since the opposite side too uses them. What will happen when the war ends is unknown." The fact that Starlink only checks a bank card during registration

is confirmed by Jakub Janowski.

Radio Liberty's "Topmashiny" said that they register accounts for "Russian" Starlink systems in Poland.

Since when using the terminal, payment is made through the seller’s bank card, the buyer will not have access to his personal account, says Radio Liberty’s interlocutor involved in the sale of Starlinks.

“There were many cases where people started trying to order Starlinks from our cards and so on, so we reserve access for ourselves and set a password for Wi-Fi upon request.” If the buyer has his own bank card, issued, for example, in Kazakhstan, he can apply for access to himself (although the “left” first and last name will still be indicated in his personal account).

Our interlocutor claims that the terminals he sells were brought not from the UAE, but from Europe, but does not specify which country, citing the fact that he is only engaged in sales. The price of one terminal in this company is 250 000 rubles, subscriptions to network services are about 14 000. Transferring goods from hand to hand is possible in the Russian capital, but the terminal can also be sent by courier service.

Jakub Yanovsky

writes that it is not possible to control the process of purchasing Starlink systems - as is the case with other civilian goods used by both sides in the Russian-Ukrainian war, for example,

motors for drones .

“As for export control, this is civilian equipment that is freely sold in dozens of countries (even in random supermarkets and electronics stores, where it can be bought for cash), and its purchase is not regulated in any way,” the expert states.

-

The test was prepared with the participation of the Sistema investigative project.