“War economy”: Russia ceasing payments after 2024?

- Pierre-Marie Meunier

- April 24, 2024

Money remains the sinews of war, in Russia as elsewhere, and the invasion of Ukraine is costing it dearly. With its assets abroad frozen and under massive sanctions, Russia has been forced for two years to draw on its financial reserves, including the National Welfare Fund, its sovereign wealth fund and its main reserve of liquidity at its disposal to balance its budget. In the absence of a major change in its current budgetary trajectory, Russia will see the depletion of this sovereign fund at the end of 2024, with the consequence of an abysmal budget deficit in 2025 that Russia will no longer be able to compensate. A situation that Russia has already experienced once, between 1988 and 1991 in particular, the last years during which it was still called the USSR.

Russia is faced with an insoluble equation: how to finance in the long term a war for which expenses are exploding while budgetary revenues are decreasing, in a context of reinforced sanctions? Between increased taxation, falling hydrocarbon revenues, inflation and employment and investment crises, Russia has embarked on a risky bet from which it will not emerge unscathed. Now spinning at high speed on the momentum of the “war economy”, the top Russia cannot slow down, otherwise it will fall. But momentum could soon run out along with finances. Russia's economic future after 2024 is essentially based on the price of the barrel of the Urals and on the quantities exported, two subjects that are all the more uncertain for Russia in 2024 as, after this date, Russia may no longer be able to rely on depleting financial reserves.

How to interpret the figures for the 2023 Russian budget?

According to the Russian Ministry of Finance, in

2022 , Russia spent 31,131 billion rubles for 27,825 billion in revenue, therefore with a deficit of 3,306 billion (or approximately 33 billion euros, considering that it is necessary in January 2024 approximately 100 rubles for one euro). Noting, however, that inflation was estimated at

13.8% over the year with, unsurprisingly, a GDP deflator high at

15.8%.

Apart from 2020, the year of the pandemic, 2022 is the first year of deficit in the Russian federal budget since the fall of the USSR. Same in

2023 , Russia spends 32,364 billion current rubles over the year (+4% compared to 2022, which would explain part of Russian growth according to

the research firm Asterès ) for 29,123 billion in revenue ( almost 5% increase over one year), with a stable deficit on the balance sheet at 3,241 billion rubles (around 32 billion euros).

This apparently linear progression of the different indicators between 2022 and 2023 actually hides significant disparities.

On the spending side , Russia has made no secret of a drastic increase in budgets devoted to defense and security, with military spending estimated at more than

6,000 billion rubles in 2023 (i.e. 3.9% of GDP) against 2.7% in 2021. In the same way, given the pre-election year, social spending has been maintained, or even increased.

On the revenue side, things are more complex. Russian revenues are budgetarily distributed between “hydrocarbon” revenues (oil and gas) and the rest, so-called “non-hydrocarbon” revenues (VAT, income tax, etc.). However, while oil and gas revenues collapsed by 24% between 2022 and 2023, going from 11,586 billion rubles to 8,822, “other”, non-hydrocarbon revenues fell from 16,238 billion rubles to 20 301, up 25% year-on-year.

Concretely, while in 2021, 36% of Russian federal state

expenditure is covered by revenues from hydrocarbons, this is only the case for 27% of expenditure in 2023. The difference is apparently made up by this 25% increase in these “other” revenues.

Behind these “other” revenues, we mainly find revenues from VAT (related to domestic production and imports) which represent around 60% of this subtotal. They thus increased by almost 22% over one year, a figure to be compared with Russian growth of 3.5% in 2023.

Second line of revenue, income tax revenue (around 10% of revenue) increased by almost 15%, to be linked to the increase in wages and the very low unemployment rate. The evolution of these two accounting lines – VAT and income tax – is therefore consistent, in terms of trend at least, with what we know about Russia's economic situation.

But there remains around 30% of “other” revenues which are not detailed, but which still saw an increase of 27% between 2022 and 2023: around 5,000 billion rubles in revenue became 6,700 billion in 2023, without it being explained where these sums come from and what explains this significant increase. If it is neither VAT nor income tax, what is it?

A 2023 trade balance in free fall

This increase in Russian revenues in 2023, which remains largely unclear, cannot be explained by the Russian trade balance. Indeed, according to

2023 data from the Russian Central Bank (BCR) recently put online, Russia exports less in 2023 than in 2022, whether goods or services: in value, exports of goods and services fell by 29 and 17% respectively between 2022 and 2023, but imports of goods and services increased by 10 and 5% respectively.

As a result, Russia's trade surplus will barely exceed 50 billion US dollars in 2023, while it was 238 billion in 2022, and 122 billion in 2021, a drop of almost 80% year-on-year. . 2022 was certainly a record year for Russian exports (more by price effect than by volume effect, due in particular to the dizzying rise in gas prices in the summer-autumn of 2022), but that was before Western sanctions on oil come into force.

To give a broader idea, Russian imports of goods and services in 2023 are almost identical in value to those of 2021, the last “ordinary” year: around 304 and 75 billion dollars respectively. On the other hand, from 2021 to 2023 exports of goods and services fell from 494 billion dollars to 422, and from 56 billion dollars to 41, respectively.

If the price of a barrel of Ural crude only experienced a significant dip in 2020 (Covid year), it almost never fell below

$55 per barrel after this date. On the other hand, the price of gas fell

significantly in 2023 after the peaks of 2022. The drop in export revenues in 2023 is therefore probably due to the drop in gas prices, combined with the loss of European customers: 40% of European gas came from Russia before 2022 compared to

15% at the end of 2023 .

The 2023 Russian trade balance simply confirms what the figures from the Ministry of Finance were already saying: the increase in Russian budgetary revenues would come primarily from the increase in taxation in Russia (excluding VAT and income tax). From September 2022, the Russian government has decided to make tax contributions to oil and gas companies, with the stated aim of recovering

628 billion rubles from 2023 .

Voted in August 2023 , an additional tax of 10% on profits was decided for companies with more than $10 million in turnover in Russia, including foreign companies. If this text initially spares companies in the oil and gas sector, the government decided a month later to also increase taxes on this sector. This time he hopes to withdraw around

$37 billion in taxes over the period 2023-2025. However, it is not obvious that this fiscal objective will be achieved, considering for example that Gazprom's income having

collapsed by 40% in 2023 compared to 2022 and by 42% compared to

2021 , another

record year before 2022. As a result, the company pays significantly less taxes than before: if the company were the first contributor to the state budget in 2022 with

5,380 billion rubles paid , it would have to pay “only” 2,500 billion rubles in 2023 (i.e. less than in 2021 with

3,310 billion rubles that year), despite the increase in taxation.

It is therefore difficult to consider that the increases in Russian revenues are entirely based on the increase in taxation, which does not prevent the Russian government from already thinking about the

next tax increases.

Drains from the National Welfare Fund

In addition to the

loans that Russia can still contract on its domestic market (around 2,500 billion rubles in 2023), the share of "unknown" origin of Russian revenue would also probably come from significant drains on the Russian reserve fund, its large sovereign fund, the

National Welfare Fund (NWF) – the Russian “nest egg” into which oil revenues are normally deposited to finance pensions and infrastructure.

Indeed, in January 2024, we can read, in a

cryptic press release from the Russian Ministry of Finance on the use of the NWF, the following: “part of the funds from the National Social Protection Fund deposited in accounts with the Bank of Russia in the amount of 114,947 million Chinese yuan, 232,584 kg of gold in impersonal form and 573 million euros were sold for 2,900,000 million rubles. The revenue was credited to a single account in the federal budget to finance its deficit. » Over the whole of 2023, Russia withdrew 2,900 billion rubles, or around 29 billion euros, from its “savings account”.

It is therefore not a priori a question of "budgetary revenue", but of a consumption of financial reserves, all the more necessary since Russia no longer has access to international financial markets: Russia is considered to be in default of payment since 2022. Sanctioned by both the EU and the United States, it cannot issue debt in dollars or euros. The principle is not necessarily very embarrassing for Russia because, with the exception of 2020, it has always managed to generate a budget surplus. But Russia is now "forbidden to overdraft" by Western countries (knowing that even China is showing itself

more and more reluctant to finance Russia): whether it has a low or even non-existent debt is of no importance considering that it can no longer really go into debt, as Western states do. The federal state budget deficit must therefore be financed differently.

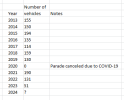

This use of the NWF is in any case not exceptional, it had already taken place in 2022 for an amount of

2,412 billion rubles , the Russian Ministry of Finance having sold off its reserves of Japanese yen, dollars and of pounds sterling, currencies deemed “toxic” by the Russian authorities. The 2023 drain was not unexpected either: the Russian Ministry of Finance announced it in

August 2023 . In the same press release, he also announced the amount planned for 2024: 1,300 billion rubles, an amount therefore twice as low. Does 2024 look better for Russian finances? Nothing is less sure.

The economic context of Russia

Already, the 2024 growth prospects are more measured than those for 2023. The Russian central bank (BCR) is still on

a forecast of 0.5 to 1.5% . If the IMF has recently been more optimistic (between

1.5 and 2.6% ), the World Bank

is more measured . In any case, let us remember that Russian growth is artificial growth, “purchased on credit”. It is a Russian-style Keynesianism, aimed primarily at the military-industrial complex, as explained by

Alexandra Prokopenko , former BCR official and speaker today for the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. At the end of December 2023, the BCR also warned of a risk of

overheating in the Russian economy .

This overheating is seen first and foremost in the Russian unemployment rate, because below a certain threshold of frictional unemployment (job changes, professional transitions, training, etc.), an unemployment rate equivalent to that currently experienced by Russia Russia above all reflects a labor shortage: at the end of 2023, the Russian media reported a labor shortage estimated at

4.8 million jobs . In August 2023, the Russian Minister of Digital Development already mentioned a

shortage of 500 to 700,000 workers in the IT fields, in addition to the 400,000 unfilled positions in the defense industry, which is in high demand at the moment. This problem of lack of IT workers in particular could compromise the future of certain Russian flagships such as Yandex, whose “

nationalization” Russia has just finalized at great expense . According to Oleg Deripaska, Russian oligarch in the metallurgy and mining sector, the basic problem is above all that of investment in production structures, with industries that are too poorly automated compared to their Western equivalents and therefore still highly labor intensive. of work. This reality is particularly glaring in

the production of armored vehicles , these being mainly assembled “by hand” in factories poorly equipped with assembly robotics, for example.

Investment is probably one of Russia's major problems for the years to come, in addition to inflation: it is very expensive for Russian companies to take on debt to invest currently given the prohibitive interest rates practiced, with the Russian central bank maintaining a key rate at

16% for the moment . For many Russian companies, there are no possible investments either with debt ratios which have exploded due to the fall in valuations: the RTSI stock index is down 40% compared to October 2021 (the MOEX index lost nearly 25% over the same period), date of the first concerns about a Russian invasion of Ukraine, knowing in addition that the real valuation of Russian companies, particularly those recently placed under government responsibility , is highly

questionable .

Added to this internal constraint in Russia is

the fall in foreign investments in Russia, in reality representing a real disinvestment given the sales of assets of companies leaving Russia: $27 billion in foreign investments in 2021, against 40 billion withdrawals in 2022 and 8 billion in 2023. The consequences of the labor shortage and limited investments in infrastructure (

1.3% of GDP between 1995 and 2016 ) are starting

to be seen , to the point that even the

Russian media were forced to talk about serial accidents on urban heating networks, among other things.

Concerning inflation, this is the BCR's number one concern for the years to come. In

November 2023 , when presenting its forecasts for 2024, the BCR mentioned a “Risk scenario” in these terms: if inflation becomes “out of control”, the BCR could then be required to raise its key rate to 16 or 17% in 2024. This was a month before raising its key rate to 16%, with inflation in 2023 estimated at 7.5%, far from the range of 4 to 4.5% desired by the BCR. Still according to the BCR, which chooses

its words carefully , the persistence of high inflation is due to “domestic demand which exceeds the growth in production capacity for goods and services much more than estimated”. However, given the labor shortage, the fall in certain investments (

$315 billion in “stocks” of foreign direct investments in September 2023 compared to 442 in December 2022 for example) and the ambitions of the Kremlin to further increase military spending in 2024, it is very unlikely that inflation will decrease in 2024. In January 2024, the BCR reported inflation still being high during its

first press release of the year on this subject.

Pitäisin nyt ehkä kuitenkin yleisemmällä tasolla ymmärrettävämpänä termiä kulutussota.

Pitäisin nyt ehkä kuitenkin yleisemmällä tasolla ymmärrettävämpänä termiä kulutussota.