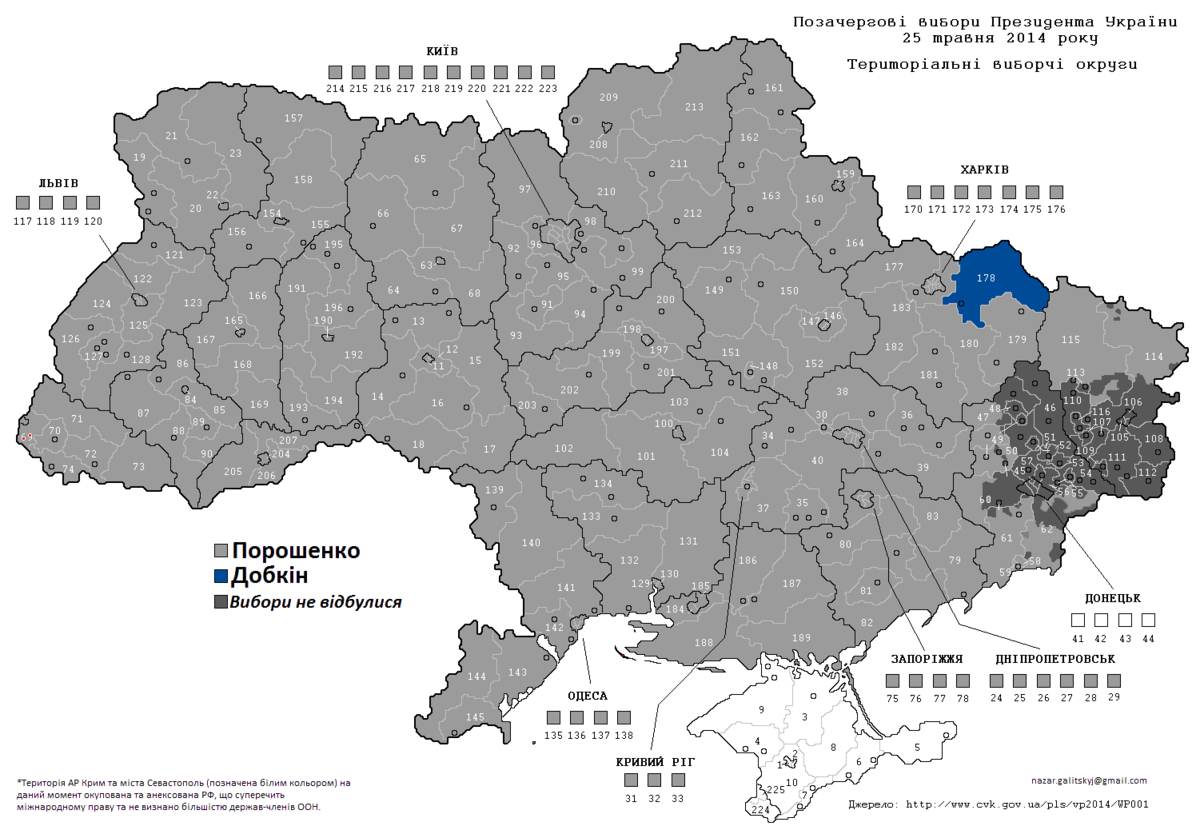

Minulla on vahva epäilys, että Venäjä olisi hyökännyt ukrainan kimppuun jo

vuosia aikaisemmin (2014-2015) elleivät olisi tunaroineet vaalitulosten manipolointia. Alkuperäinen suunnitelma joka feilasi oli, että vaaleihin olisi manipuloitu voittajaksi äärioikeistolainen kandidaatti jonka oikea kannatusprosentti maanlaajuisasti oli tuohon aikaan mielipidekyselyiden mukaan alle prosentin luokkaa. Venäjä olisi saanut hyvän casus bellin Ukrainan operaatiolle jossa tulisi vapauttamaan kansan presidentistä joka a) oli äärioikeistolainen ja b) epäsuosittu kansan keskuudessa. Tämän skenaarion onnistuessa venäjällä olisi jopa saattanut olla takanaan ukrainan kansan tuki ja OMON + VDV olisivat riittäneet lähes varmasti "erikoisoperaatioon".

Tämä on aika hyvin dokumentoitu tapaus, joten siitä mitä tapahtui ei ole epäilyksen häivääkään. Mikä jää arvailujen varaan on kuinka hyvin operaatio olisi onnistunut yllä annetuilla ehdoilla.

Lähde:

Muuta jossa mainintaa tästä - liittyy lähinnä venäjän harjoittamaan informaatiosodankäyntiin:

Russian cyber operations have gained increasing amounts of attention as nations around the world react to cyber threats. The strategies of Russian cyber operators can be unveiled, as seen here, by looking into past attacks and how they were devised and played out.

international-review.org

It isn't the first time Kremlin-linked hackers have been accused of trying to influence voters in other countries, reports NBC News.

www.cnbc.com

en.wikipedia.org

Tuosta on myös se videoklippi jossakin.

Totta, tästä ollaan samaa mieltä. Olisi pitänyt kirjoittaa selkeämmin: tarkoitin ainoastaan tätä vuonna 2021 alkanutta joukkojen keskittämistä ja sitä, missä vaiheessa olivat valmiit hyökkäämään.

Hyvin moni Venäjän eri portaissa oli sitä mieltä, että sota olisi pitänyt viedä loppuun saakka 2014-2015. Jostain syystä näin ei kuitenkaan tehty. Jos katsoo mitä venäläiset kirjoittavat, niin monen mielestä sota alkoi 2014 eikä ole loppunut vielä. Näin se on rehellisyyden nimissä nähtävä: he jatkoivat sodan tukemista koko tämän ajan eri muodoissa, missään vaiheessa ei ollut tavoitteena rauhan aikaansaaminen ja palaaminen vuotta 2014 edeltävään tilanteeseen.

Olen tämän sodan myötä palauttanut mieleen syksyn 2008 tapahtumia sekä sitä seurannutta EU:n energiapolitiikkaa. Sotien osalta on hyvin paljon samankaltaisuuksia, energiapolitiikan osalta puolestaan nähtävissä 14 vuotta jatkunut epäonnistuminen. Halvan energian nimissä Venäjän on annettu mellastaa miten tykkää eikä voida sanoa etteikö heidän tapaansa toimia olisi tiedetty. Se nähtiin viimeistään 2018 ja ihan heidän omista sisäisistä dokumenteista:

EU documents lay bare Russian energy abuse

Mitä on tehty sen jälkeen? Aika vähän, sanoisin - lisätty riippuvuutta Venäjän energiasta eikä vahingossakaan ole investoitu kilpaileviin vaihtoehtoihin. Pohjanmereltä Puolaan vedettävä Baltic Pipe on yksi positiivinen tapaus, sen pitäisi valmistua tämän vuoden aikana (olettaen ettei ryssä tee temppuja).

Missä helvetissä viipyy "Nabucco pipeline"? Reuters kirjoitti siitä vuonna 2014:

Don’t cry for the Nabucco pipeline

Lainaan alle pätkän, tosin artikkelin lopussa on hyvä neljäkohtainen suosituslista, joka kannattaa vilkaista. Surullista luettavaa sinänsä näin kahdeksan vuotta myöhemmin.

Many factors contributed to Nabucco’s failure, but the main reasons were political rather than commercial. The pipeline was replaced by a more modest plan to upgrade and expand the Southern Corridor, which includes the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline that will carry Azerbaijan gas from the Turkish border into Greece and Italy.

The selection of the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline in late 2013 left a bitter taste in Europeans’ mouths. The pipeline will bring Azeri gas to Italy, which already has fairly diverse energy sources, while Nabucco, even in its smaller version (known as

Nabucco West), would have supplied gas to EU member states — notably Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania — largely dependent on Gazprom.

The first lesson of Nabucco’s failure is that Russia’s carrot-and-stick approach not only worked, it also exposed the lack of a common EU energy policy. Moscow was able to safeguard its dominant market share in Central and Eastern Europe, where Gazprom faces little competition. Moscow pressured most of these countries to support Gazprom’s South Stream pipeline, a rival to Nabucco. That pipeline was developed to bring Russian gas into Eastern and Southern Europe.

The European Commission tried to protect countries like Lithuania by launching an

antitrust investigation in 2012 to determine whether Gazprom might be hindering competition. Gazprom, however, was not punished and was allowed to continue its anti-competitive practices. There were not enough political guarantees at the EU level for the Central and Eastern European states to withstand the threat of retaliation by Gazprom. In addition, the lack of a united EU energy policy continues to encourage Russia to play the national interest card by fostering strong bilateral energy relations — such as the

Germany-Russia cooperation.

Baku was also concerned about geopolitical considerations. It was important for Azerbaijan to be wary of taking too much too fast from Gazprom’s European market share. Moscow would have seen that as a direct threat. Azerbaijan, however, could have been more assertive if the EU and the United States had offered stronger support.

The second lesson is that the Caspian region is a clear loser in the

U.S. energy revolution. Washington has historically played a role in Caspian energy development because of regional strategic interests and volatility generated by the competition among major powers for Eurasia’s oil and gas reserves — comparable to the gas reserves of Russia and Iran, among the world’s largest. U.S. engagement has helped stabilize the Caspian region and kept product flowing toward the West, rather than letting Russia, China and Iran monopolize it.

But the revolution in U.S. shale oil and gas has prompted Washington’s energy policy to turn inward — giving the nation less of a stake in some of the energy hotspots around the globe. In addition, the Obama administration has more pressing foreign policy priorities than Caspian energy. Yet growing tensions in Ukraine and risks of contagion to other former Soviet republics may soon test Washington’s disengagement.

Overall, the Nabucco pipeline lacked the necessary political and diplomatic support from both the EU and the United States to overcome disarming pressures from Russia and Gazprom.