-TripleX-

Respected Leader

Sateliittikuva siitä taannoin räjähtäneestä ruutitehtaasta. Tuon uudelleen rakentaminen lähtee liikkeelle piirrustuspöydältä ja tiilen polttamisesta.

Kaput

Kaput

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Kuriositeettina, tai toivottavasti ennakkotapauksena, yksi ryssän suurimmista droonivalmistajista menossa nurin:

AO Kronstadt (Orion yms dronet) on kärsinyt ilmeisesti pakotteista tilausmäärien noustessa: https://defence-blog.com/russias-leading-drone-maker-nears-collapse/

$7 miljoonaa perinnässä, summa ei kuulosta isolta valtion panostaessa sotatalouteen, joten sinänsä ”outo” uutinen.

Mutta hyvä jos ei enää pystytä menemään 5-vuotissuunnitelmilla, joihin markkinatalouden realiteetit eivät vaikuta?

Ja Ukrainan iskut tuotantoon vielä rikkana rokassa

Rekkarissa on regioonakoodi 45, joka on Uralilla oleva Kurganin oblasti, eli keski-etelä ryssälän moskaleitaTiesivät tasan tarkkaan mitä tekevät. Taustalla on länsiautot ja niitä on monta eli ei ole ihan perusvatnikit liikkeellä. Vesimeloni on Khersonin alueen tunnus. No sen paukun z:tan tuntee kaikki ja lada esittää ryssälää. Kuvaa siis täydellisesti nykytilannetta.

Talous kestää pitempään neuvostomoodissa, mutta mikä sen Neuvostoliiton talouden romahduttikaan?Eli kyllä se neuvostoliitto 2 on tekeillä oikeasti. Nyt kulakkia tai tehtaanomistajaa ei ammuta, kunhan älyää olla suopea markkinatalouden muutoksille.

Omistajuus säilyy ulkomaille varastetulla rahalla jos henki säilyy...Pajarijärjestelmässä ei ole omistajuutta vaan hallintaoikeutta. Martti J Karin kirjassa tätä avataan kansantajuisesti.

Talous kestää pitempään neuvostomoodissa, mutta mikä sen Neuvostoliiton talouden romahduttikaan?

Ukrainaketjua ei kannattaisi sotkea persu- ja pakolaispsykooseilla. Muuten voi käydä niin, että afrikkalaisista kortonkiautomaateista saa banaania.Ero on tosiaan melkoinen. Nämä meidän kylän ukrainalaiset ovat työllistyneet hyvin, kun ottaa huomioon paikalliset olosuhteet. Tosin en tiedä saavatko yritykset jotain tukea työllistämiseen.

Afrikka on suuri ja afrikan sarven asukkaat eivät ole koko afrikan kuva. Meillä on afrikkalaisista kuva, jossa kärpäset syövät lapset ja kortonkiautomaateista saa tavaraa banaaneilla. Sieltä tulee ihan fiksua väkeä, aasialaiset oma lukunsa positive.

Sitten sisältövaroitus persuille, ei kannata lukea:

Älämölö refugeelapsista a muutama kymmenen on silkkaa pakolaispornoa omalle kultille. Nämä ukr aasia afrikka tulijat tuntevat todella hyvin perheenyhdistämiskuviot jo tullessaan. Ja taivahan varmasti tämä mekanismi muuttaa suomen väriskaalaa ym. Ilmiöitä volyymilla, josta riikka ja jussi eivät halua hönkiä mitään. Muutaman kymmenen lapsen päältä reuhaaminen on silkkaa ihtiään, silkkaa höpötöpöä omalle kannatusväelle. Ei niin mitään merkitystä isossa kuvassa, ei edes sitä hitua höpöttimessä.

Varsin synkkä näkemys, mutta ihan realistinen. Minä tunnen syvää myötätuntoa ukrainalaisia kohtaan, ja lahjoitan joka kuukausi sidetarpeita keräykseen. Jos/kun putlerin erikoisoperaatio saadaan loppumaan, niin tulee väkisinkin mieleen se, kuinka paljon rintamalta palaa PTSD:stä kärsiviä miehiä, ja naisia - jotka sitten lääkitsevät itseään vodkalla? Puhumattakaan mahdollisien palaavien sotavankien tilanteesta.Asia on tietysti selvä, kun joku on paennut Ukrainasta, mitään huonompaa lännestä tuskin on luvassa. Ehkä se oma lahjuspyramidikin on siinä sivussa luuhistunut. Sinällään kaikkea hyvää näille Ukrainasta paenneille.

Suomessa taloustilanne on erittäin huono ja kaikista kauniista puheista huolimatta, mitään selkeää valoa tai työvoimapulaa ei ole nähtävissä vaikka sitä on hoettu jo 30 vuotta. Ostakoon ukrainalaiset (luultavasti valtion maksamilla tukiasilla) mieluumin asuntoja Suomesta kuin joistakin kolmansista maista tulleet. Tämä on kuitenkin Ukrainan kannalta hyvin huolestuttava kehityssuunta ja oletan, että tähän ryssätkin pyrkivät: kulut muille ja tyhjä tai tyhjennettävä maa ryssille. Kaikella kunnoituksella, itse tunnen jo myötäsääliä Ukrainan urhoollisia taistelijoita kohtaan. Kun sota on saatu joskus päätökseen, mikä näitä sankareita odottaa? Onko se paraskin skenaario tyhjä maa, joka on vaupautettu ryssistä, mistä naiset ja lapset ovat paenneet Länteen. Siinä ei jää paljon muuta jäljelle kuin mahorkka ja vodka, kokeneelle sankarille molemmat jo luultaavasti tuttuja kavereita 4 vuoden harjoittelun takaa.

Vain lahjuspyramidissa sisällä olleilla voi olla jotain merkittäviä rahoja läntisessä mittakaavassa - kenelläkään muulla Ukrianasta ei, ellei satu olemaan joidenkin harvojen suurliikemiesten sukua.

Ukrainaketjua ei kannattaisi sotkea persu- ja pakolaispsykooseilla. Muuten voi käydä niin, että afrikkalaisista kortonkiautomaateista saa banaania.

Suomessa taloustilanne on erittäin huono ja kaikista kauniista puheista huolimatta, mitään selkeää valoa tai työvoimapulaa ei ole nähtävissä vaikka sitä on hoettu jo 30 vuotta. Ostakoon ukrainalaiset (luultavasti valtion maksamilla tukiasilla) mieluumin asuntoja Suomesta kuin joistakin kolmansista maista tulleet. Tämä on kuitenkin Ukrainan kannalta hyvin huolestuttava kehityssuunta ja oletan, että tähän ryssätkin pyrkivät: kulut muille ja tyhjä tai tyhjennettävä maa ryssille. Kaikella kunnoituksella, itse tunnen jo myötäsääliä Ukrainan urhoollisia taistelijoita kohtaan. Kun sota on saatu joskus päätökseen, mikä näitä sankareita odottaa? Onko se paraskin skenaario tyhjä maa, joka on vaupautettu ryssistä, mistä naiset ja lapset ovat paenneet Länteen. Siinä ei jää paljon muuta jäljelle kuin mahorkka ja vodka, kokeneelle sankarille molemmat jo luultaavasti tuttuja kavereita 4 vuoden harjoittelun takaa.

Tärkeä asia muistaa tässä bensa/diesel suhteessa on se että öljynjalostus ei luo vaan erottelee olemass aolevaa materiaali tislauksella. Ei ole erikseen bensa tai diisel jalostamoa vaan samasta materiaalivirrasta ne erotellaan. Jalostussuhteen määrää öljyn laatu ja ryssän öljy on raskasta eli siitä tulee suhteessa enemmän diiseliä kuin bensaa. Tätä suhdetta voi vähän kääntää kräkkeriyksiköillä bensan eduksi mutta tämä on länsitekniikkaa.Sergey Radchenko (twitter-tilin bio = Historian of the Cold War and after. Wilson E. Schmidt Distinguished Professor @KissingerCenter @SAISHopkins) kehui kovasti tällaista tuoretta artikkelia:

The best take I've seen on this is Vakulenko's analysis (in Russian):

https://carnegieendowment.org/russi...asoline-problem?lang=ru¢er=russia-eurasia

Vakulenko doesn't think this adds up to much tbf.

-

I think this is the link for the article in English.

https://carnegieendowment.org/russi...asoline-problem?lang=en¢er=russia-eurasia

https://carnegieendowment.org/russi...asoline-problem?lang=en¢er=russia-eurasia

Can Russia Weather a Fuel Crisis Caused by Ukrainian Drone Attacks?

Damage to Russian refineries has helped send gasoline prices to multi-year highs, but the government has options to mitigate the shortages.

English

by Sergey Vakulenko

Published on August 26, 2025

Carnegie Politika is a digital publication that features unmatched analysis and insight on Russia, Ukraine and the wider region. For nearly a decade, Carnegie Politika has published contributions from members of Carnegie’s global network of scholars and well-known outside contributors and has helped drive important strategic conversations and policy debates.

Once again, Russia is in the grips of a gasoline crisis. Prices at the pump are rising, and some gas stations have run dry. This isn’t the first time Russia has experienced such shortages, but this time around they could be more serious because of the ongoing war in Ukraine.

There were gasoline crises in Russia both before the full-scale invasion (in 2011, 2018, and 2021), and afterward (in 2023). Despite a 2024 Ukrainian drone campaign targeting Russian refineries, the fuel market remained relatively calm. Back then, each refinery was only hit by a single drone, reducing plant capacity but leaving it operational. The damage was dealt with in a matter of weeks, consecutive attacks, were rare and often deflected, and neighboring plants continued to operate without interruption. Ultimately, the 2024 drone attacks caused inconvenience and expense for the Russian oil industry, but did not present a major problem.

The drone attacks that began on August 2, 2025, have been different. Ukraine clearly has more drones now, and can send out attack swarms numerous enough to overwhelm Russia’s air defenses. Drones also have better navigational capabilities. Ukraine’s tactic this year has been to launch massive attacks on refineries and inflict maximum damage—up to and including shutdowns. Ukraine has also carried out rolling attacks, with some damaged refineries hit again, hindering repair work.

By the middle of August, Kyiv had succeeded in damaging Russia’s Ukhta, Ryazan, Saratov, and Volgograd refineries, as well as the three refineries in the Samara group (Syzran, Samara and Novokuibyshev). Refineries in the Rostov and Krasnodar regions have also been regularly attacked.

The Ukhta refinery is not that important for the domestic market as it is small and outdated, and supplies a region (the Komi republic) with low demand that can in any case be met by the Perm and Yaroslavl refineries. The Rostov and Krasnodar region refineries are mainly export-oriented. However, the attacks on the refineries located in an arc from Ryazan to Volgograd could have a serious impact on the domestic market. Tens of millions of Russians live to the west of this arc, where there are also large areas of agricultural land, and many popular vacation destinations.

Another fundamental difference from the 2024 drone attacks is that back then, the campaign peaked in May. This year it began in August: a time when the oil market’s systemic problems traditionally come to the fore. This is when demand rises for gasoline: it’s harvest season, boosting demand in the agricultural sector, and people are using their cars for vacations. At the same time, supply is reduced because of annual maintenance work at refineries.

The first sign of an imbalance between supply and demand is rising prices. Usually, this is the mechanism whereby balance is restored to the market—but the Russian authorities long ago established formal and informal price controls for the retail fuel market in an attempt to limit gasoline price rises and even out seasonal spikes. This policy reduces the effectiveness of market signals and discourages producers from increasing supplies or stockpiling. Of course, under normal circumstances the sector’s excess capacity should mean that refineries can ensure the market remains well-supplied. But there are limits.

Since 2019, the government’s primary tool for regulating the domestic fuel market has been so-called dampener payments that compensate oil companies for selling fuel on the domestic market when it is less lucrative than the export market. In the 2023 gasoline crisis, the government tried to drastically reduce these payments, which led to local shortages—and it was forced to backtrack.

This year, the issue has not been dampener payments. Instead, drone attacks have caused delays and cancelations to air travel and disrupted train schedules, prompting an increase in the use of cars for long-distance journeys and pushing up demand for gasoline. This has been particularly noticeable in the areas between Moscow and the Black Sea coast that are popular with vacationers.

In addition, the indirect impact of high interest rates on the gasoline market has been to reduce stockpiling for the summer. Wholesale gasoline prices in Russia rise almost every year at the end of summer, which creates an incentive to buy gasoline at lower prices in the spring, put it in storage, and sell at a profit later. However, high interest rates on commercial loans now mean that this can be loss-making, while regulation has made it risky to assume the price of gasoline traded on the mercantile exchange will rise. As an apparent result, there is less gasoline being released from storage this summer than usual.

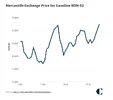

Despite the controls, wholesale gasoline prices began to climb in the spring, and in June, they surpassed last year’s record. Since the start of August, prices have risen rapidly, exceeding the record of the gasoline crisis year of 2023.

Katso liite: 124234

Retail prices have consistently increased every week this year by between 15 kopecks ($0.0019) and 25 kopecks a liter. The gradual nature of this increase is the result of the government’s coercive efforts where oil companies are concerned, and an informal ban on sharp rises. In the week beginning August 18, the wholesale price (53.5 rubles for a liter of A-92 gasoline) approached the retail price (59.5 rubles per liter). For comparison, in mid-July, the wholesale price was 47.72 rubles per liter, and the retail price was 58.5 rubles per liter.

Right now, the situation looks challenging but manageable. Most of the refineries that have been hit by Ukrainian drones continue to produce gasoline, albeit in reduced quantities. It has also been possible to redirect gasoline from unaffected regions, and some of the deficit has been eased by tapping state reserves.

It’s important to remember that a lot of Russian vehicles and military equipment run on diesel, not gasoline, and Russia has a diesel surplus. Accordingly, the sort of full-scale fuel crisis that could end up impairing the functioning of the economy—or the army—is still a long way off.

On top of this, annual gasoline production in Russia exceeds domestic demand by up to 20 percent, while diesel production is more than double what is needed. Even if the damaged refineries (which account for about 20 percent of primary refining capacity) stopped functioning entirely, the resulting deficit would be small—and could be offset by imports (from Belarus, for example). Ukrainian attacks on the Unecha and Nikolskoye pumping stations on the Druzhba oil pipeline, which supplies Belarus, among other countries, could theoretically lead to the stoppage of Belarusian refineries. But following an August 18 attack on the pipeline, repairs were swift, and Druzhba was fully functional again within two days.

That said, larger shortages could push the government to more extreme steps. The simplest option would be for officials to abolish all price controls, allowing the market to balance supply and demand—including by redirecting fuel to deficit-stricken regions. While effective, this would cause short-term suffering for ordinary Russians, particularly farmers, and it goes against the government’s increasingly dirigiste instincts. But in an emergency, it’s possible an exception could be made (just as the central bank is allowed to pursue a tight monetary policy). Other options for officials would be to temporarily relax standards on motor fuel and allow the country’s mini-refineries to sell their off-grade products as motor fuel. If the worst comes to the worst, a crisis measure would be gasoline rationing.

For now, however, none of this appears imminent. There is still a long way to go before the transport, agriculture, and industrial sectors—or, most importantly, the army—experience any significant fuel shortages.

-

Yksi tuon kantavista teeseistä on se että sotilasajoneuvot kulkevat pääasiassa dieselillä ja Venäjän diesel-tuotanto on kaksikertaa suurempi kuin kotimaan kysyntä. Eli drone- ja ohjusiskuilla ei ole tässä mielessä nopeasti vaikutusta kykyyn jatkaa sotaa. Lisäisin myös diesel-veturit sekä kotimaan kumipyörälogistiikan kuorma-autot ja yhdistelmät, nekin kulkevat valtaosaksi dieselillä.

Toisaalta bensiinin kapasiteetti on 1,2 kertaa suurempi kuin kotimaan kysyntä, joten tässä ei ole niin suurta puskuria. Hän myös kommentoi että kapasiteetin menetystä voidaan ainakin osaksi kompensoida lisäämällä ulkomailta tuontia mm. Valko-Venäjä. Ukraina iski Druzhba putken pumppausasemalle ja artikkelissa kirjoitetaan että vahingot saatiin korjattua parissa päivässä. Tosin Ukraina iski uudestaan tämän jälkeen, mitä ei mainita artikkelissa.

Artikkelissa esitetään myös muutamia vaihtoehtoja polttoainepulan torjumiseksi mm. laatuvaatimuksista tinkiminen jolloin erilaiset "mini jalostamot" voivat myydä omaa tavaraansa vapaammin (tämä tuskin on hyvä ratkaisu autokannan näkökulmasta, pitkässä juoksussa).

Jäädään seuraamaan tilannetta. Toivottavasti iskut jatkuvat ja osuvat purevasti. Sama juttu yleisesti polttoainelogistiikan osalta eli polttoainejunat ja -putket. Se on selvää että nämä iskut eivät ole "merkityksettömiä" vaan erittäin kalliita ja kivuliaita, mutta lisää tarvitaan.

-

Sergey Radchenko jakoi myös tällaisen hyödyllisen linkin:

There is a useful website for monitoring average Russian gasoline prices:

https://autotraveler.ru/russia/dinamika-izmenenija-cen-na-benzin-v-rossii.html

Retail prices have increased 7.66% since January 1, 2025.

Tuottaa rikkipotoista dieseliä jolla länsiautot nipin napin kulkevat ja takana haistaa ja haistoi ennen Suomessakin, kun maketusvaiheena tunnettu rininpoisto oli jäänyt välistä. Moottorit pyörivät mutta saasteenpoistot himmenevät. Tosin tuolla, "bce ravno".Igorin erkkapurkkapaikattu jalostamo siis tuottaa matalaoktaanista bensaa ja kohtuullisen kelvoillista diiseliä.