Denmark, having been one of the original European partner nations of the F-16 program and having operated a shrinking fleet of F-16’s ever since, is facing roughly the same issue as Finland, with a US teen-series fighter nearing the end of it life. To remedy this, the Danish launched the

Kampfly-program (literally “Fighter aircraft”), with the aim of finding a suitable replacement. Now, what is interesting is that the Danish did this

despite already being a F-35 tier 3 partner nation. The idea was that a fair and relatively open competition, not unlike the HX-program, would show which fighter was the right choice for replacing the Danish F-16AM/BM mix, and if this wasn’t the F-35A, the Danish would withdraw from the program.

Few people believed that would ever be the case.

In fact, so few people believed in it, that of the F-35’s four main competitors, two, Dassault with the Rafale and Saab with the Gripen E, decided to withdraw from the competition at an early stage. When asked about the issue during the

HX Gripen-presentation in February, Saab avoided calling the competition unfair or predetermined, but noted that “one has to focus attention on where one’s chances of winning are the best”. This left the Eurofighter Typhoon and Boeing F/A-18F Super Hornet in the running against the F-35A Lightning II.

Especially Boeing went all-in, including launching a serious marketing campaign promoting itself as the low-risk high-tech solution, an argument being especially useful in Denmark, which a few years back was the site of a

disastrous attempt at introducing a new and unproven high-speed train. After a series of technical issues, both the price and delivery schedules were seriously derailed, and the affair took on a slightly absurd twist when a complete train set went missing before delivery, only to turn up on

satellite images of the outskirts of Tripoli! The whole affair also became something of a political issue.

Examples of adverts directly referencing the IC4-debacle. Note that these are for illustrative purposes only, and I have not received any compensation for featuring them on the blog.

Examples of adverts directly referencing the IC4-debacle. Note that these are for illustrative purposes only, and I have not received any compensation for featuring them on the blog.

During the recent weeks, the outcome (and part of the selection criteria) have slowly been leaking out, and unsurprisingly the F-35A was declared the winner in more or less all categories, with the Eurofighter Typhoon scoring low points throughout. The choice is justified in an open report, which include an abstract also available in English. The abstract covers the description of the criteria, the deciding panel, source material (but no individual notes confirming which sources were used where), and the points scored on different criteria. Still, the information given on why a certain fighter scored a certain point value doesn’t feel exhaustive.

The lack of transparency in the Danish report makes it hard to judge the fairness of the competition. However, there are a number of issues that cast a shadow on the process. One is that the Super Hornet is evaluated only in the two-seat F/A-18F configuration. It is unclear whether this is a request on the part of Boeing or not, however, it places the Super Hornet at a drawback, as the report correctly notes that maintaining two persons proficient for each aircraft will increase the total amount of flight hours needed,

without apparently accounting for the added flexibility of having a dedicated weapons and sensor operator in the back seat.

The real strange part is the table of projected life-cycle costs. This is of particular interest, as it is one of the few places were solid numbers are provided. The Danish life-cycle costs is calculated based on procurement costs, sustainment costs (i.e. actually operating the aircrafts bought), as well as an overhead titled ‘Risk’. The last one is described as ‘quantifiable risks over a period of 30 years’, but the interesting part is that despite the Super Hornet being ranked highest in the earlier military ‘non-quantifiable risk’-subcategory, when risk is quantified and getting a price tag the tables are turned and the Super Hornet scores a markedly higher price tag than the F-35A. This is mainly blamed on the risk associated with the DKK-USD exchange rate. The report notes that as the F-35A is designed for a service life span of 8,000 flight hours compared to 6,000 flight hours for the other two, only 28 F-35A’s are needed to perform the same missions as 34 Eurofighters and 38 Super Hornets respectively over a 30 year time span.

This is an extreme oversimplification.

Using this model does not take into account e.g. the fact that fewer airframes in total leads to fewer available airframes, as there will at any given time be a number of aircrafts undergoing maintenance, repairs, or upgrades. That you are flying fewer aircraft harder usually doesn’t add up to having a higher availability rate either, but on the contrary might even lead to a shorter mean-time between failures, further putting added strain on a small fleet. It is also hard to quantify whether a smaller number of more capable aircraft will be able to provide the same overall capability as a slightly higher number of less capable aircraft. Strength in numbers, and so forth. The idea that you will only need a certain number of flight hours, as opposed to aircraft, add to the feeling that an all-out war is not on the agenda in Copenhagen.

However, the lifetime given for the airframes are also controversial. Both Boeing and Eurofighter have also

protested the choice of 6,000 flight hours. Boeing notes that the number refers to taxing carrier-based operations, with the aircraft easily being able to reach 9,500 flight hours during landbased operations, while Eurofighter states that their aircraft can reach 8,300 flight hours in the kind of operations envisioned by Denmark. It is entirely possible that they are correct, as how demanding a flight hour is varies greatly with factors such as height, loadout, and g-forces (something which Finnish Hawks and Hornets have demonstrated, when the high proportion of air combat maneuvering in the Finnish flight schedule have caused structural problems even at relatively low flight hours).

Also, no mention is made of the

service life extension program(SLEP) launched by Boeing and the US Navy, aimed at lengthening the service life of their Super Hornets up from the original 6,000 hours. The exact scope of the program is still unclear, but as a point of reference the US Marine Corps’ F/A-18C/D legacy Hornets are already looking at 10,000 flight hours through a similar SLEP-program.

Ironically, the need for these extensions have arisen due to delays in the F-35 program.

The main enemy in the report is the Su-30MK, one of the most advanced Russian-built fighters currently available. The report gives the PL-12 as the OPFOR’s BVR-missile, which indicates the Chinese Su-30MKK version illustrated here. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Dmitriy Pichugin

The eventual unit price for a series-produced F-35A is one of the most hotly debated topics in defence aviation today, and the issue has featured on the

blog as well. Suffice to say, the Danish report uses 83.6 million USD per aircraft, being 10 million USD over the unit flyaway cost predicted by manufacturer Lockheed-Martin,while the ptice today is a tad over 100 million USD (though this is sinking rapidly). For the Super Hornet, the price is 124 million USD, which is 14-17 million USD over both the quoted cost for the current

deliveries to the US Navy and, more importantly, the export deal to Kuwait (110 and ~107 million USD respectively). For the Eurofighter, there isn’t much to say. The heavy twin-engined fighter is expensive, both to acquire and operate, and its main selling point will always be its brute force, advanced sensors, and, most importantly, impressive room for growth. However, the report also gives it the highest ‘Risk-cost’, which is surprising given that the aircraft has an impressive track record in the service of multiple air forces for well over a decade, including combat deployments. The price set for the Eurofighter is 126 million USD per aircraft, which matches nicely with the average price tag of 124.9 million USD per aircraft that the

British RAF has paid for their aircraft. However, this does not take into account the fact that for the Eurofighter as well, the price has continuously come down, and BAE has been quoted as saying they are now producing the aircraft for 20% less than they used to.

The fact that all aircraft are priced over the current, or in the case of the F-35A, projected, unit flyaway cost, is likely due to the acquisition topic also covering associated costs such as supporting material, simulators, and so forth. The unit flyaway costs given by the manufacturers have been censored from the open version of the report.

For the other categories, much less concrete information is given. For strategic aspects, the F-35 outscore the other candidates as the “broad scope of […] users will foster both Denmark’s transatlantic ties and the country’s collaborative relations with a range of European partners.” The Eurofighter score some points for opening up the possibility of cooperating with a number of European partners as well, with Germany standing out. The Super Hornet benefits from the transatlantic aspect, but defence and security cooperation with Kuwait and Australia is not high on the Danish agenda.

This is probably the most truthful part of the evaluation, and it is hard to argue against it. The big question is how important this aspect of an arms deal is, something we will get back to later.

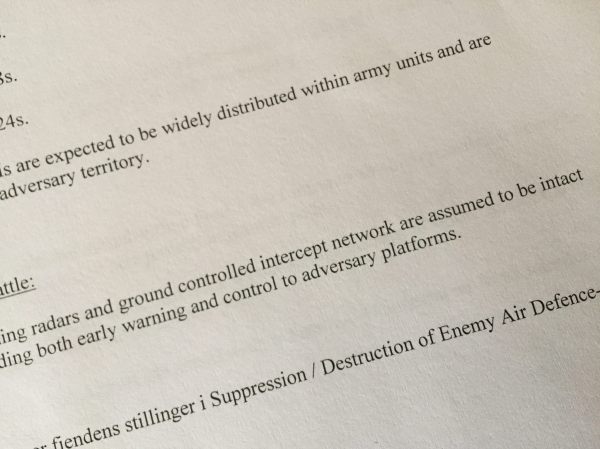

A typical scenario in the evaluation missions, with air defence systems “widely distributed” and “radars and ground controlled intercept networks intact”. Source: Nytkampfly.dk

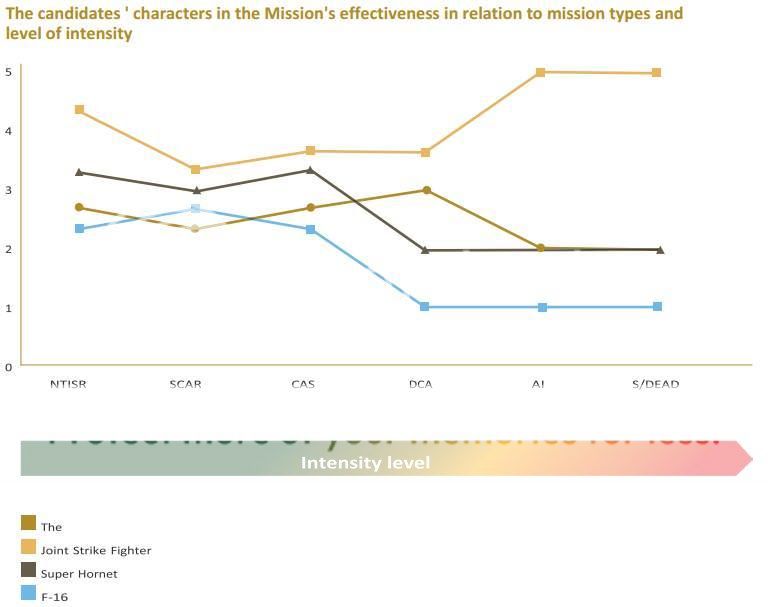

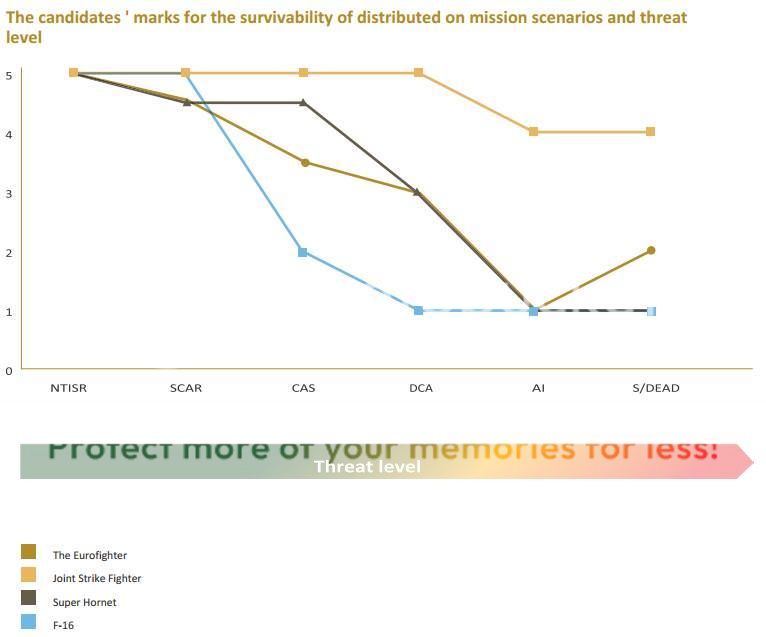

The military category is made up of the areas of survivability, mission effectiveness, future development potential, and the earlier mentioned (non-quantifiable) candidate risk. These have been scored based on a number of evaluation missions, which haven’t been released to the public. However, they have been leaked, and

described as “probably the closest thing to a ‘smoking gun’” we are likely to see, referring to the suspicion that the program has been tuned to suit the F-35. Of the six missions, four are against well-equipped and relatively modern adversaries, featuring strong air-defence assets and/or modern fighters, with the sixth being a deployment to the Greenland (which curiously enough currently isn’t home to any Danish fighters as part of the Danish decision to not further ‘militarise’ the Arctic). Perhaps the thoughest scenario is the defensive counter air setup against ten Su-30MK and MiG-29SMT escorting four Su-24’s and a single 3M14 Kalibr cruise missile (SS-N-30A), the fighters all having jammer pods, with the whole package being supported by an additional two Su-30MK operating as jammer aircraft (while still holding a serious air-to-air load) and a Beriev A-50 airborne early warning aircraft.

An interesting details is that for the air interdiction mission, the report indicates that F-16AM would have the same (low) chance of survival as the Eurofighter and Super Hornet!

It can be argued that the evaluation should be benchmarked against the most demanding mission the aircrafts are expected to fly. However, it is a rather strange notion that the Danish fighters would be expected to penetrate advanced enemy defences without the support of other NATO-allies, especially as the prospects of strategic cooperation is scored as a category of its own. All in all, it does seem that there is a tilt towards the high-end spectrum of missions which

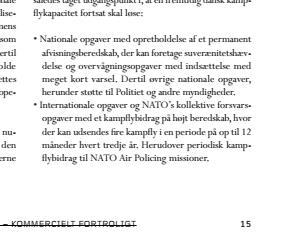

doesn’t match the mission scope set out in the beginning of the Danish version of the report.

The planned mission scope according to the report: maintaining a national QRA readiness, support to other government agencies, such as the police, and international tasks in support of NATO. The last in the form of up to four aircraft being deployed for up to 12 months every third year, as well as periodic detachments as part of NATO Air Policing missions.

The F-35 also wins the Industrial aspects-category, despite the fact that there is a “particular element of uncertainty associated with the fact that the Joint Strike Fighter will not be subject to an industrial cooperation requirement”, and that the realization of the industrial initiatives are “conditioned upon the ability of the Danish defence industry to win contracts in accordance with the ‘best-value’ principle”.

The tragicomic thing is that the F-35A might very well be the best fit for the Danish fighter requirement, either based on military aspects alone or thanks to the strategic impact the choice has. A sensible case can also be made for joining the F-35 program at an early stage, trading risk-management for being able to influence the program from the get-go. However, the lack of transparency unfortunately make it seem like the Danish officials had settled on the F-35A before the evaluation, but weren’t ready to defend this decision. Instead, launching the “fair and open competition”, which was in fact anything but.

This also means that in the same way as the two runner-ups, the F-35 didn’t get a chance to prove itself. Instead, it will probably go down in history as a very potent fighter, but one that landed in Denmark due to events that weren’t quite fit to see the daylight. One can only hope that the Finnish HX-competition will not follow this unfortunate example, but instead continue with the transparent and well-argued information sharing culture adopted so far.

https://corporalfrisk.com/2016/05/15/how-not-to-choose-your-fighter-the-danish-kampfly/