D

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ilmasota

- Viestiketjun aloittaja Ikarus

- Aloitus PVM

D

Deleted member 1262

Guest

Jos tuota piipitystä meinaat, niin se on alasammutun lentäjän paikannuslaitteen piipitystä CSAR-operaatiota varten. Sama on kuultavissa oheisessa videoklipissä, kun SA-2-ilmatorjuntaohjus nappaa F4:n pois taivaalta:28:45, siis tosiaan tuollaisia tietokonepelien ääniä on ollut olemassa, hieman vakavammassa tarkoituksessa vain...

Kyllä muuten kuulee, kun jätkillä äänenpainot nousee..

JR49

Respected Leader

Kyllä. Tuo oli muutenkin jännä B-52 -video, kirjoista tutut radiokutsut, kuten Punainen Kruunu, ja tuosta paikannuslaitteesta samoin kuin ohjuslukituksen varoitusäänestä lukenut paljon. Mielenkiintoista kuulla ne livenä, kuin haudan takaa.Jos tuota piipitystä meinaat, niin se on alasammutun lentäjän paikannuslaitteen piipitystä CSAR-operaatiota varten. Sama on kuultavissa oheisessa videoklipissä, kun SA-2-ilmatorjuntaohjus nappaa F4:n pois taivaalta:

Kohta 3:25.

Skyrider olisi kyllä varsinainen "tankki" lennettäväksi...

Vietnamiin liittyen pätkä Skyraidereiden käytöstä pelastuskoptereiden saattona.

Kone oli tulivoimainen ja ''sopivan'' hidas roikkumaan kopterin mukana.

Tässä dramatisoinnissa loukkaantunut lentäjä tilaa lastin ''Sandyltä'' omaan niskaansa.

Tuota loukkaantunutta lentäjäähän näytteli tässä Willem Dafoe. Ihan mukava leffa toi Flight of the Intruder.

Vietnamiin liittyen pätkä Skyraidereiden käytöstä pelastuskoptereiden saattona.

Kone oli tulivoimainen ja ''sopivan'' hidas roikkumaan kopterin mukana.

Tässä dramatisoinnissa loukkaantunut lentäjä tilaa lastin ''Sandyltä'' omaan niskaansa.

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Tuota loukkaantunutta lentäjäähän näytteli tässä Willem Dafoe. Ihan mukava leffa toi Flight of the Intruder.

Hyvä ja yllättävän realistinen minusta. Ei sinällään ihme kun elokuva pohjautuu saman nimiseen kirjaan, jonka kirjoittaja on entinen A-6 Intruder -pilotti.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flight_of_the_Intruder_(novel)

JR49

Respected Leader

Löytypäs kiinnostava pätkä. Vietnamiin jääneitä koneenromuja. Sodan rujoja muistomerkkejä. Mutta tsekatkaapas kohta 1:16. Siinä on muistotaulu juurikin Linebacker II:n aikana alasammutusta B-52:sta, mutta tällä kertaa näkökulma on vietnamilainen. Ovat tietenkin ylpeitä, kun saivat pudotettua noin mahtavan koneen.

Lopusta 2:50 kannattaa katsoa, kun Flying Banana on kyljellään tulessa ja kyydissä ollut/lentäjä pakenee. Tuhannen taalan osuma valokuvaajalla.

Lopusta 2:50 kannattaa katsoa, kun Flying Banana on kyljellään tulessa ja kyydissä ollut/lentäjä pakenee. Tuhannen taalan osuma valokuvaajalla.

Tässä mielessä ilma-ase näytti voimansa

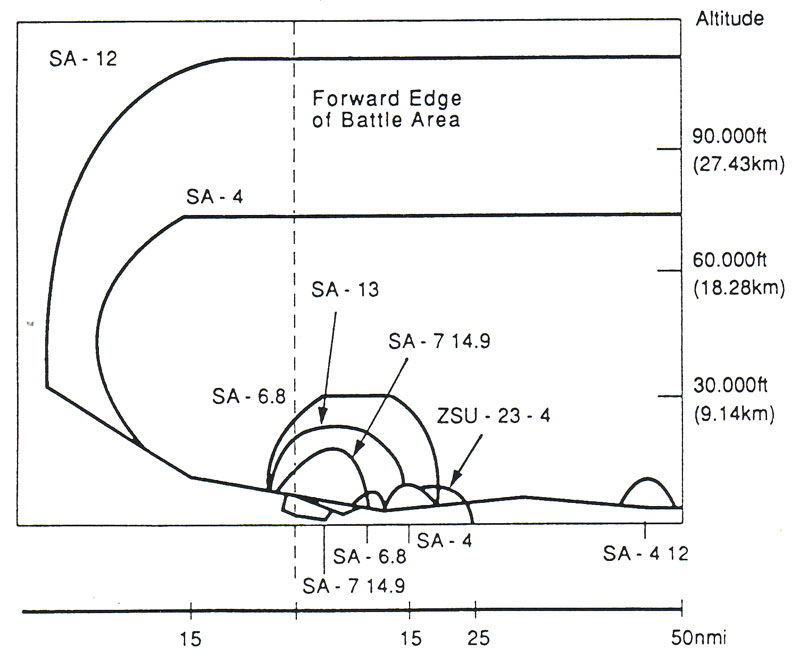

Niin tuo ilma-ase oli suunniteltu toimimaan aivan toisaalla.

Ja jos sen toimita vietnamin ilmatilassa (pääsy kohteeseen) edellyttää noin laajoja toimenpiteitä.

Miten se pystyy suunniteluissa kolmannen maailmansodan olosuhteissa toimimaan?

Maallikkona voisi luulla että amerikkalaisille oli yllätyksenä kuinka työläs oli suhteellisen heikon puolustuksen läpäiseminen.

Joka johti varmaan suuriin muutoksiin ilmavoimien käytössä ja taktiikassa Euroopassa.

Myös neuvostoliito sai arvokasta tietoa niistä olosunteitta missä sen ilmapuolialustuksen tulisi toimia.

Tietoa tuli myös siitä miten aseita tulisi käyttää noissa olosuhteissa.

Vaikka tappiot pienenivätkin niin todennäköissetti se olisi ollut vain väliaikaista.

Sillä myös vihollinen (vietnamilaiset) oppivat.

( Jossain oli maininta että lopussa vietnamilaisia vaivasi ohjus pula.

Mutta he olivat myös oppineet käyttämään niitä paremmin noissa olosuhteissa.)

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Niin tuo ilma-ase oli suunniteltu toimimaan aivan toisaalla.

Ja jos sen toimita vietnamin ilmatilassa (pääsy kohteeseen) edellyttää noin laajoja toimenpiteitä.

Miten se pystyy suunniteluissa kolmannen maailmansodan olosuhteissa toimimaan?

Maallikkona voisi luulla että amerikkalaisille oli yllätyksenä kuinka työläs oli suhteellisen heikon puolustuksen läpäiseminen.

Joka johti varmaan suuriin muutoksiin ilmavoimien käytössä ja taktiikassa Euroopassa.

Myös neuvostoliito sai arvokasta tietoa niistä olosunteitta missä sen ilmapuolialustuksen tulisi toimia.

Tietoa tuli myös siitä miten aseita tulisi käyttää noissa olosuhteissa.

Vaikka tappiot pienenivätkin niin todennäköissetti se olisi ollut vain väliaikaista.

Sillä myös vihollinen (vietnamilaiset) oppivat.

( Jossain oli maininta että lopussa vietnamilaisia vaivasi ohjus pula.

Mutta he olivat myös oppineet käyttämään niitä paremmin noissa olosuhteissa.)

Toteaisin kyllä, että 1972 Pohjois-Vietnamin ilmapuolustus oli kaikkea muuta kuin heikko. En nyt muista ulkoa ilmatorjuntatykkien, MiG -hävittäjien, ilmavalvontatutka-asemien ja ilmatorjuntaohjuspattereiden määriä, mutta puolustus oli kyllä todella vahva. Vuoden 1968 jälkeen Yhdysvallat ei käytännössä lentänyt lainkaan sotalentoja Pohjois-Vietnamin yllä (pois lukien tiedustelulennot), joten Neuvostoliitto ehti toimittaa 1968-72 välillä valtavat määrät kalustoa ja kouluttaa väkeä käyttämään tutkia ja ohjuksia.

Amerikkalaiset olivat tietysti tästä tosiseikasta varsin hyvin perillä ja tiesivät kyllä, että mikään läpihuutojuttu Hanoin rusikoiminen ei tulisi olemaan. Suurin ero aiempaan vuosien 1965-68 Rolling Thunder -ilmaoffensiiviin oli se, että poliitikot eivät enää sekaantuneet liikaa sotatoimien johtamiseen ja toteuttamiseen. Nixon esikuntineen määritteli tarkasti vain halutun poliittisen tavoitteen (= P-Vietnamin saaminen takaisin Pariisin rauhanneuvotteluihin) ja itse toteuttaminen jäi paikallistason komentajille. Aiempien vuosien täysin älyttömät Washingtonin määräämät millintarkat voimankäyttösäännöt aiheuttivat vain turhia tappioita ja tehottoman ilmasodan.

fulcrum

Greatest Leader

Pitää muistaa että B-52:lla oli tarkoitus lentää ydinpommittamaan NL:ää. Silloin olisi ollut siedettävää vaikka 50% koneista olisi ammuttu kerralla alas - jäljelle jäänyt puolisko olisi silti hoitanut homman. Konventionaalinen väsytyspommitus toistuvine lentotehtävineen on tilastollisesti aivan eri tilanne, ja siinä 5% tappiotkin tehtävää kohden alkavat olla liikaa.

John Hilly

Respected Leader

Muoks. Lue seuraava posti ensin! Pitkä juttu Iranin-Irakin ilmasodasta. Osa 2

‘An F-14A taking off from Khatami for a photo-session after the end of the war with Iraq, carrying the full armament load of two Sidewinders, two Sparrows and four Phoenix missiles. Photo via Tom Cooper

Iraq Did All It Could to Kill Hashem All-e-Agha, Iran’s Top F-14 Pilot

It took two MiGs and a lot of luck to take him down

by TOM COOPER

Part two of two. Read part one.

During the first four years of the Iran-Iraq War, one Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force F-14 pilot earned a fearful reputation — especially in Iraq. Amazingly enough, he remains entirely unknown to the public, even in Iran.

This might unsurprising, considering Iran’s fascistic regime and its ongoing efforts to falsify not only the history of its armed forces, but of the entire country. However, the lengths officials have gone to to avoid acknowledging Iran’s top F-14 pilot are quite extraordinary.

Contrary to standard practice in Iran, there are no magazine articles about Hashem All-e-Agha, no books, no spectacular movies, no T.V. documentaries and no murals decorating the streets of Iranian cities. Tehran apparently doesn’t want the world to how one of its deadliest aerial warriors ultimately fell in battle.

As the deputy commander of Tactical Fighter Base 8 near Esfahan, All-e-Agha was the mastermind of many Iranian air-defense operations during the first four years of the Iran-Iraq War that began in 1980.

His planning resulted in the IRIAF scoring around 40 confirmed kills and establishing aerial dominance over the oil-rich Khuzestan province, in turn enabling Iranian ground forces to launch a series of offensives that gradually pushed the Iraqi forces out of the country in 1981 and 1982.

However, on Nov. 15, 1981, the Iraqi Air Force hit back when its Dassault Mirage F.1 interceptors shot down two of IRIAF’s vaunted F-14 Tomcats. Determined to recover not only the shattered morale of his pilots, but also the aerial dominance in the skies over Khuzestan, All-e-Agha developed a plan.

Although risky, his plan worked better than anyone expected. All-e-Agha first imposed a complete ban on all other aerial activity of Iranian aircraft and helicopters — except for his interceptors. While leaving much of ground forces exposed to Iraqi air strikes and without any helicopter support, this measure enabled Iranian F-14 crews and their ground controllers to operate free of usual problems with sorting out own from enemy aircraft.

They enjoyed full freedom of operation, and were cleared to fire as necessary.

On Nov. 25, 1981, a pair of Tomcats from TFB.8 deployed on the same patrol-station occupied by the pair that was shot down four days earlier. At a pre-determined point in time, their crews made a fake radio call announcing they would be short of fuel and about to return to base.

One of last known photographs of All-e-Agha — standing, third from the left — showing him together with the F-14A 3–6053 and a group of pilots from the 81st TFS at Khatami air base in 1983 or 1984. Tom Cooper Collection

A few minutes later, the pilots of two low-flying F-5E Tigers sighted a pair of brand-new Iraqi MiG-23MFs approaching the area below the Iranian patrol-station in a tight formation at a very low altitude.

The Tigers were much too slow to follow, but their warning was sufficient. Both Tomcats performed a vertical descending maneuver known as a “split s.” The crew of the lead F-14 — Capt. Fazlollah “Javid” Javad-Nia and 1st Lt. Gholamreza Khorshidi — quickly acquired one of their low-flying opponents with their AWG-9 radar, set up an attack and launched an AIM-54 Phoenix missile before flying another vertical maneuver known as the “F-pole.”

In this fashion, their Tomcat flew down and to the side of the incoming enemy, while still keeping its radar pointed on the target in order to provide course corrections for the Phoenix missile.

Converted from hunters into a prey in a matter of few seconds, the two Iraqis now fought for their survival. Each fired one R-23R medium-range air-to-air missile. Too late. Out of the three missiles that were airborne, Javid’s Phoenix was not only the first fired, but also the fastest. It blotted out the lead MiG-23. The debris of the smashed fighter struck the other MiG.

One of Iraqis was killed, the other ejected and was captured by the Iranians. Left on their own, both of the R-23Rs missed their targets.

With MiG-23MFs out of the way, the IRIAF’s Tomcats had a field day. By sunset on Nov. 25, 1981, they scored five additional confirmed kills, effectively sweeping the skies clean of the Iraqi Air Force.

Loppu jutusta linkissä https://warisboring.com/iraq-did-al...-irans-top-f-14-pilot-bbd4c6a48313#.2sluoau15

‘An F-14A taking off from Khatami for a photo-session after the end of the war with Iraq, carrying the full armament load of two Sidewinders, two Sparrows and four Phoenix missiles. Photo via Tom Cooper

Iraq Did All It Could to Kill Hashem All-e-Agha, Iran’s Top F-14 Pilot

It took two MiGs and a lot of luck to take him down

by TOM COOPER

Part two of two. Read part one.

During the first four years of the Iran-Iraq War, one Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force F-14 pilot earned a fearful reputation — especially in Iraq. Amazingly enough, he remains entirely unknown to the public, even in Iran.

This might unsurprising, considering Iran’s fascistic regime and its ongoing efforts to falsify not only the history of its armed forces, but of the entire country. However, the lengths officials have gone to to avoid acknowledging Iran’s top F-14 pilot are quite extraordinary.

Contrary to standard practice in Iran, there are no magazine articles about Hashem All-e-Agha, no books, no spectacular movies, no T.V. documentaries and no murals decorating the streets of Iranian cities. Tehran apparently doesn’t want the world to how one of its deadliest aerial warriors ultimately fell in battle.

As the deputy commander of Tactical Fighter Base 8 near Esfahan, All-e-Agha was the mastermind of many Iranian air-defense operations during the first four years of the Iran-Iraq War that began in 1980.

His planning resulted in the IRIAF scoring around 40 confirmed kills and establishing aerial dominance over the oil-rich Khuzestan province, in turn enabling Iranian ground forces to launch a series of offensives that gradually pushed the Iraqi forces out of the country in 1981 and 1982.

However, on Nov. 15, 1981, the Iraqi Air Force hit back when its Dassault Mirage F.1 interceptors shot down two of IRIAF’s vaunted F-14 Tomcats. Determined to recover not only the shattered morale of his pilots, but also the aerial dominance in the skies over Khuzestan, All-e-Agha developed a plan.

Although risky, his plan worked better than anyone expected. All-e-Agha first imposed a complete ban on all other aerial activity of Iranian aircraft and helicopters — except for his interceptors. While leaving much of ground forces exposed to Iraqi air strikes and without any helicopter support, this measure enabled Iranian F-14 crews and their ground controllers to operate free of usual problems with sorting out own from enemy aircraft.

They enjoyed full freedom of operation, and were cleared to fire as necessary.

On Nov. 25, 1981, a pair of Tomcats from TFB.8 deployed on the same patrol-station occupied by the pair that was shot down four days earlier. At a pre-determined point in time, their crews made a fake radio call announcing they would be short of fuel and about to return to base.

One of last known photographs of All-e-Agha — standing, third from the left — showing him together with the F-14A 3–6053 and a group of pilots from the 81st TFS at Khatami air base in 1983 or 1984. Tom Cooper Collection

A few minutes later, the pilots of two low-flying F-5E Tigers sighted a pair of brand-new Iraqi MiG-23MFs approaching the area below the Iranian patrol-station in a tight formation at a very low altitude.

The Tigers were much too slow to follow, but their warning was sufficient. Both Tomcats performed a vertical descending maneuver known as a “split s.” The crew of the lead F-14 — Capt. Fazlollah “Javid” Javad-Nia and 1st Lt. Gholamreza Khorshidi — quickly acquired one of their low-flying opponents with their AWG-9 radar, set up an attack and launched an AIM-54 Phoenix missile before flying another vertical maneuver known as the “F-pole.”

In this fashion, their Tomcat flew down and to the side of the incoming enemy, while still keeping its radar pointed on the target in order to provide course corrections for the Phoenix missile.

Converted from hunters into a prey in a matter of few seconds, the two Iraqis now fought for their survival. Each fired one R-23R medium-range air-to-air missile. Too late. Out of the three missiles that were airborne, Javid’s Phoenix was not only the first fired, but also the fastest. It blotted out the lead MiG-23. The debris of the smashed fighter struck the other MiG.

One of Iraqis was killed, the other ejected and was captured by the Iranians. Left on their own, both of the R-23Rs missed their targets.

With MiG-23MFs out of the way, the IRIAF’s Tomcats had a field day. By sunset on Nov. 25, 1981, they scored five additional confirmed kills, effectively sweeping the skies clean of the Iraqi Air Force.

Loppu jutusta linkissä https://warisboring.com/iraq-did-al...-irans-top-f-14-pilot-bbd4c6a48313#.2sluoau15

Viimeksi muokattu:

John Hilly

Respected Leader

Nämä menivät väärin päin. Tässä pitkä juttu Iranin-Irakin ilmasodasta. Osa 1

https://warisboring.com/hashem-all-e-agha-was-irans-top-f-14-pilot-9aeeb0bc5675#.ixx9r46uy

All-e-Agha in a classic pose, together with one of first 32 F-4Es delivered to Iran starting in 1971. Tom Cooper Collection

Hashem All-e-Agha Was Iran’s Top F-14 Pilot

But Tehran has tried to bury his memory

by TOM COOPER

Part one of two. Read part two.

During the first four years of the Iran-Iraq War, one Iranian F-14 pilot earned a fearful reputation — especially in Iraq. Amazingly enough, he remains entirely unknown to the public, even in Iran.

This might seem unsurprising, considering Iran’s fascistic regime and its ongoing efforts to falsify not only the history of its armed forces, but of the entire country. However, the lengths officials have gone to to avoid acknowledging Iran’s top F-14 pilot are quite extraordinary.

Tehran apparently doesn’t want the world to how one of its deadliest aerial warriors ultimately fell in battle.

The man in question was Hashem All-e-Agha — sometimes spelled “Alagha” — an officer and pilot about whom, contrary to standard practice in Iran, there are no magazine articles, no books, no spectacular movies, no T.V. documentaries and no murals decorating the streets of Iranian cities.

All-e-Agha’s early career was typical for an Iranian fighter pilot of the 1970s. Upon completing his basic and elementary training, he converted to the Northrop F-5 with the 43rd Tactical Training Squadron at the Tactical Fighter Base 4 at Vahdati outside Dezful, and then to the McDonnell Douglas F-4E Phantom II at the Tactical Fighter Base 1 at Mehrabad in Tehran.

Quickly recognized as a quick thinker, in 1976 he was selected to convert to the Grumman F-14 Tomcat with the second group of Iranian pilots to do so. Following extensive training in the United States, he returned to Iran in 1978 as a fully-qualified instructor pilot.

The centerpiece of Iranian Tomcat operations was Tactical Fighter Base 8 near Esfahan. Originally named “Khatami” after a legendary commander of the air force who died in a kite-flying accident, the purpose of this huge installation could be directly compared with that of America’s Naval Air Station Oceana — or of the former NAS Miramar, also known as “Fightertown USA” in the 1980s.

Khatami was constructed in the mid-1970s with the sole purpose of serving as a home for a wing equipped with 40 F-14s plus all of its personnel and their weapons and workshops.

The first F-14A Tomcat manufactured for Iran. The aircraft was re-serialled as 3–6001 immediately upon delivery. Tom Cooper Collection

Reviving the Tomcat

Following the Islamic revolution of 1979, the Iranian Tomcat fleet was largely grounded. Bamboozled by immense costs of operating such complex aircraft, the new regime even attempted to sell its F-14s to Great Britain and Turkey. Negotiations collapsed once the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps occupied the U.S. embassy in Tehran and kept its personnel as hostages for 444 days.

Meanwhile, Khatami air base became one of best examples for post-revolutionary chaos in Iran. Most top officers were either arrested or forced to retire and many others banned from entering the facility, while the air base was repeatedly occupied and controlled by all sorts of political activists, religious leaders and unruly non-commissioned officers.

Amid the complete chaos, each of the cliques in question attempted to impose its own rule upon the usual chain of command. By August 1980, the new commander of this strategically important facility, Col. Sadeghpour, had barely enough crews left to maintain and operate a handful of Tomcats.

The situation began to improve when Tehran ordered the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force to improve its overall condition in the light of increased tensions along the border to Iraq. The possibility of a major armed conflict turned Iran’s F-14s into a strategically important asset, and a massive effort was launched to return them to service.

Acknowledged as a quiet and controlled professional, All-e-Agha was appointed the deputy commander of TFB.8, with the task of providing refresher training to as many F-14 crews as possible. Working himself and his personnel very hard, by mid-September 1980 he flew more than 40 sorties, re-training around two dozen pilots, many of whom hadn’t flown for up to 18 months.

In contrast to most of his pilot colleagues, All-e-Agha didn’t neglect his radar intercept officers in the two squadrons based at Khatami. While in the U.S. military the front- and back-seater in a combat aircraft share responsibilities and achievements, in the Iranian air force — and even in units equipped with F-14s, where good cooperation between the crew is of paramount importance — the RIO was considered a second-class citizen, a mere passenger who could help the pilot if asked him to do so, but otherwise was expected to shut up.

In complete ignorance of that tradition, and despite his rank and status, All-e-Agha voluntarily flew as RIO not only while re-training his pilots, but also during some of combat sorties early in the Iran-Iraq War. He encouraged other pilots to do the same, eventually resulting in the IRIAF equalizing the official status of its F-14 pilots and RIOs.

Eventually, even the new regime learned to appreciate his administrative and organizational skills and through November 1980, All-e-Agha — who was not religious — was permitted to coordinate the operations of his interceptors with those of multiple intelligence agencies.

On his initiative, the Direct Air Support Center was established in Ahwaz. The center controlled all aerial operations over the battlefield in Khuzestan. This was supported by several mobile early warning radar stations and two Lockheed R/C-130H Khoofash signals-gathering aircraft capable of tracking the activity of Iraqi air defenses and reading encrypted Iraqi telecommunications in real time.

A combination of these assets and the IRIAF’s F-14s enabled the Iranians to establish a sort of aerial dominance over the battlefield, resulting in a number of successful ground offensives in 1981.

Together with the air force’s young and inexperienced commander, Col. Fakkouri, All-e-Agha personally succeeded in appeasing dozens of dismissed officers and other ranks into luring them back to active service.

He was also instrumental in the re-establishment of the 11th Combat Command Training Squadron in the spring of 1981. Equipped with 11 F-5Bs, this unit became crucial for training dozens of new pilots at a time when a majority of the IRIAF’s fliers who had survived the first six months of the war were in need of rest, recuperation and refresher training.

In August and September 1981, All-e-Agha commanded a major effort by TFB.8 to again establish air superiority over Khuzestan. Under his command, F-14 Tomcats from Khatami scored at least seven confirmed kills against Iraqi fighter-bombers by Sept. 30, 1981 — all of these by AIM-54 Phoenix long-range missiles.

All-e-Agha, second from left, at NAS Oceana, early during his conversion course for F-14s in 1976 or 1977. Photo via Javad A.

An economic pilot

In air combat, All-e-Agha proved particularly economical in terms of missile expenditure.

Knowing the IRIAF was unlikely to replenish its stocks of air-to-air missiles it obtained from the USA in the 1970s, he became an expert in intimidating Iraqi pilots instead of just shooting at them.

Already awed by the powerful F-14, the Iraqis tended to run on sight and would engage in air combat only if absolutely necessary. All-e-Agha took advantage of this tendency.

Sometime in October 1982, he was flying a combat air patrol together with Ali-Reza Ataayee — the pilot who probably scored the Tomcat’s first Phoenix kill — in support of a convoy of merchant ships and tankers underway between Bandar Mahshahr and the Khark Island.

Despite detecting two incoming Iraqi Su-22s, All-e-Agha ordered Ataayee not to fire any AIM-54s or AIM-7 Sparrows — rather, to cut the range and try to force Iraqis to jettison their bombs and run away before they could cause any harm.

This plan worked. As soon as the Tomcats approached, the Iraqis saw them and made a hard turn to the west. Both Tomcats followed and a high-speed race developed, which the two Sukhois couldn’t win.

Eventually, Ataayee ran out of patience. He locked on to one of the enemies and attempted to fire. However, something went wrong with his fire-control system and the missile failed to launch.

A moment later, the lead Iraqi entered a high-G turn in attempt to maneuver around the two Tomcats. Worried by the failure of his fire-control system, Ataayee called for All-e-Agha to support him. “Relax, buddy,” the latter replied. “I can see him and it’s clear he can’t even control his aircraft.”

Quickly diving after the Sukhoi, All-e-Agha acquired with an AIM-9 Sidewinder, fired, and sent the Iraqi plummeting into the waters of the Persian Gulf.

Back at Khatami, he was congratulated by Col. Abbas Babai’e, who asked why didn’t he fire a Phoenix or a Sparrow from longer range.

“Too expensive,” All-e-Agha responded.

All-e-Agha upon his return from training in the USA in 1978. Photo via Tom Cooper

Deadly giraffes

While All-e-Agha’s planning and application of innovative combat tactics and the technical advantages of his aircraft resulted in Iranian Tomcats appearing when and where the Iraqis expected them the least, it also made their crews overconfident. Combined with the necessity of maintaining a standing CAP high in the skies between Ahwaz and Defzul, this exposed them to Iraqi retaliation.

Nov. 15, 1981, the Iraqi Air Force introduced its brand-new Dassault Mirage F.1EQ interceptors to combat in a particularly spectacular fashion.

Carefully guided by the ground control, a pair of Mirages flying at low altitude with their radars off, sneaked up on a pair of IRIAF F-14s flying a CAP between Ahwaz and Dezful. When the Mirages reached a point underneath the Tomcats, their ground control issued the code-word “giraffe” via radio. Both Iraqis then entered a steep climb, activated their radars and each fired a pair of Matra Super 530F-1 medium-range air-to-air missiles.

In this fashion, the Mirages evaded detection by Iranian early warning radars and by Tomcats and hit their opponents from an aspect from which they remained unseen until it was too late.

The loss of two F-14s was a severe shock for the IRIAF. Already battered by heavy losses during the first year of the war with Iraq, the air force’s morale was shattered by the realization that even its vaunted Tomcats were now vulnerable to the Iraqis.

All-e-Agha was determined to re-establish the IRIAF’s aerial dominance at the earliest possible moment. Correspondingly, he developed a plan for a counter-stroke through a combination of high-flying F-14s with low-flying F-5Es.

In time, the Iraqis would devise their own countertactics, meant specifically to corner and kill All-e-Agha.

https://warisboring.com/hashem-all-e-agha-was-irans-top-f-14-pilot-9aeeb0bc5675#.ixx9r46uy

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Karjalan lennoston Hävittäjälentolaivue 31:n kapteeni Juha Järvinen palvelee vaihtoupseerina lennonopettajana USA:n merijalkaväen Hornet-laivueessa. Miehen haastattelu luettavissa täältä.

http://ilmavoimat.fi/artikkeli/-/asset_publisher/lennonopettajana-hornetin-kotiseuduilla

Hornetiin liittyen, jokos iltapäivälehdet ovat ehtineet julistaa Hornetin surmanloukuksi ?

http://www.verkkouutiset.fi/ulkomaat/hornet_viat_turvallisuus-63593

http://ilmavoimat.fi/artikkeli/-/asset_publisher/lennonopettajana-hornetin-kotiseuduilla

Hornetiin liittyen, jokos iltapäivälehdet ovat ehtineet julistaa Hornetin surmanloukuksi ?

http://www.verkkouutiset.fi/ulkomaat/hornet_viat_turvallisuus-63593

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Katsomisen arvoinen dokumentti RAF:n Harrier -laivueen toiminnoista. Ei ole kovin tuore, varmaankin 90-luvulta. Mutta hyvää settiä silti.

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Nämä Youtuben Aircrew interview -kanavan videot ovat todella mainioita. Tässä pätkässä haastatellaan nuorta RAF:n Typhoon -pilottia. Kaveri kertoilee mielenkiintoista tarinaa mm. Baltic Air Policing -operaatiosta, harjoituksista ruotsalaisia Gripeneitä vastaan ja tunnistuslennoista venäläisiä koneita vastaan.

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Ilmavoimat julkaisi 22.5.-2.6 järjestettävän ACE 2017 -harjoituksen osallistujalistan.

http://www.reservilainen.fi/uutiset...nvaliseen_harjoitukseen_osallistuvan_kaluston

http://ilmavoimat.fi/artikkeli/-/as...ntaharjoituksen-lentavat-joukot-ja-tukikohdat

Mukana on mm. B-52H -pommittajia, E3A AWACS -koneita, sekä Dassaulta Aviation 20 -suihkukone ELSO -roolissa. RAF lähettää Tornado -rynnäkkökoneita, Sveitsi ja Espanja Horneteja, USAFE F-15 -koneita ja Ranska Mirage 2000- ja Rafale -hävittäjiä.

http://www.reservilainen.fi/uutiset...nvaliseen_harjoitukseen_osallistuvan_kaluston

http://ilmavoimat.fi/artikkeli/-/as...ntaharjoituksen-lentavat-joukot-ja-tukikohdat

Mukana on mm. B-52H -pommittajia, E3A AWACS -koneita, sekä Dassaulta Aviation 20 -suihkukone ELSO -roolissa. RAF lähettää Tornado -rynnäkkökoneita, Sveitsi ja Espanja Horneteja, USAFE F-15 -koneita ja Ranska Mirage 2000- ja Rafale -hävittäjiä.

tulikomento

Supreme Leader

Kertomus siitä, kuinka 80-luvulla Vidselin ampuma-alueella ohjusammunnoissa ollut Draken lähestulkoon ampui alas maalinhinauskoneena toimineen Lansenin.

http://lae.blogg.se/2017/april/idag-for-30-ar-sedan-se-dcn-nastan-nedskjuten-2.html

Jaktförband från flygvapnet besöker regelbundet Vidsel för att öva robotskjutning. Den 9 april 1987 var det dags för en J 35F Draken (35492, min anm.) från F 10 att skjuta en RB 27 Falcon-robot mot ett Del Mar 14-mål, bogserat av Lansen SE-DCN. Beroende på en för liten infallsvinkel kom roboten att negligera släpmålet och istället fortsätta fram mot bogseraren. Den låg fem kilometer framför målet, vilket gjorde att roboten mer eller mindre precis nådde fram (räckvidd cirka 10 km), och exploderade 5-10 m under flygplanet. Att den exploderade utan fysisk kontakt beror på att robotar är försedda med ett zonrör, vilket känner av när avståndet till målet är som kortast.

Lansen-planet, spakat av Christer Ohlsson, fick omfattande skador med splitterhål över stora delar av stjärtpartiet och ena vingen. Hydraultrycket försvann och alla servon måste kopplas ur, vilket gav ett mycket stort spaktryck för föraren.

Vid landningen på Vidsel fanns ingen bromsverkan, utan planet gick in i nätet vid banan slut med en hastighet av 75 km/h.

On mennyt suunnilleen niin, että Drakenin oli tarkoitus ampui Falcon -ohjus Del Mar 14 -maalilaitteeseen. Tulokulma tai lähestymiskulma oli kuitenkin pieni ja ohjus meni ohi maalista ja päätyikin seuraamaan maalinhinauskonetta, joka oli 5 kilometrin päässä. Ohjus räjähti 5-10 metriä Lansenin alapuolella. Kone sai osumia taistelukärjen sirpaleista, hydraulipaineet menivät ainakin osittain. Laskussa vaurioitunut kone päätyi jarrujen puutteen takia pysäytysverkkoon.

http://lae.blogg.se/2017/april/idag-for-30-ar-sedan-se-dcn-nastan-nedskjuten-2.html

Jaktförband från flygvapnet besöker regelbundet Vidsel för att öva robotskjutning. Den 9 april 1987 var det dags för en J 35F Draken (35492, min anm.) från F 10 att skjuta en RB 27 Falcon-robot mot ett Del Mar 14-mål, bogserat av Lansen SE-DCN. Beroende på en för liten infallsvinkel kom roboten att negligera släpmålet och istället fortsätta fram mot bogseraren. Den låg fem kilometer framför målet, vilket gjorde att roboten mer eller mindre precis nådde fram (räckvidd cirka 10 km), och exploderade 5-10 m under flygplanet. Att den exploderade utan fysisk kontakt beror på att robotar är försedda med ett zonrör, vilket känner av när avståndet till målet är som kortast.

Lansen-planet, spakat av Christer Ohlsson, fick omfattande skador med splitterhål över stora delar av stjärtpartiet och ena vingen. Hydraultrycket försvann och alla servon måste kopplas ur, vilket gav ett mycket stort spaktryck för föraren.

Vid landningen på Vidsel fanns ingen bromsverkan, utan planet gick in i nätet vid banan slut med en hastighet av 75 km/h.

On mennyt suunnilleen niin, että Drakenin oli tarkoitus ampui Falcon -ohjus Del Mar 14 -maalilaitteeseen. Tulokulma tai lähestymiskulma oli kuitenkin pieni ja ohjus meni ohi maalista ja päätyikin seuraamaan maalinhinauskonetta, joka oli 5 kilometrin päässä. Ohjus räjähti 5-10 metriä Lansenin alapuolella. Kone sai osumia taistelukärjen sirpaleista, hydraulipaineet menivät ainakin osittain. Laskussa vaurioitunut kone päätyi jarrujen puutteen takia pysäytysverkkoon.