Antares

Respected Leader

Viittasin edellisessä viestissä Neuvostoliiton tekemiin massiivisiin varusteiden siirtoihin Uralin itäpuolelle ennen CFE-sopimuksen allekirjoittamista. Seuraavassa kuvaus CFE-sopimuksesta (Conventional Forces in Europe) ja siihen liittyvistä vaikeuksista kylmän sodan päättymisen hetkellä. On hyvä tietää sopimuksen ja siihen liittyvien ilmoitusten tausta kun arvioi niiden numeroita ja luotettavuutta: LÄHDE

As Europe entered the 1990s, it was in turmoil. From 1989 to 1992-coinciding with the years of the CFE Treaty's negotiation, ratification, and entry into force-nations on the European continent were experiencing their greatest changes since the end of World War II. There was the unification of Germany; the "velvet" political revolutions casting out Communist systems in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia; the bloody revolution in Romania; the continuous integration of the European Union; the recurrent economic and political crises in the Soviet Union presaging its collapse; the national independence movements in the former Soviet republics; and, running throughout, the large-scale military withdrawals from Central and Western Europe by the Soviet Union and the United States. Politically, diplomatically, and militarily, the European continent was in the midst of revolutionary changes. It was in this context that ratification and implementation of the CFE Treaty proceeded.

In constitutional governments, treaties require two acts for legitimacy: executive signature and legislative ratification. For the United States, President Bush signed the CFE Treaty in Paris on November 19, 1990. That same day, the leaders of 21 other NATO and Warsaw Pact nations signed the treaty. Ratification, however, took nearly two years. On October 30, 1992, just 20 days short of two full years, the final two states, Belarus and Kazakstan, ratified the treaty and deposited their instruments of ratification at The Hague in the Netherlands. Why did it take so long?

One CFE Treaty signatory state, the Soviet Union, was in such turmoil in 1991 and 1992 that its very existence was in question.1 When the USSR collapsed in late December 1991, its successor states had to form new governments, and those governments had to work out military and security relationships with Russia, the largest and most powerful of the former republics.

So great were the repercussions from the Soviet Union's internal difficulties that the CFE Treaty signatory states had to convene four separate extraordinary meetings to approve, authorize, and incorporate new statements, understandings, declarations, and agreements into the treaty regarding entitlements and obligations. In June 1991, the signatory states met at The Hague; in October 1991 they convened in Vienna; in June 1992 they met in Oslo; and, finally, in July 1992, they assembled just before the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) summit in Helsinki. At each of these meetings, the diplomats took up specific treaty issues for the group to resolve before the individual states would proceed with ratification and implementation. Every issue was a consequence of the Soviet Union's collapse as an empire. Throughout these extraordinary meetings across Europe, the commitment of the European and North Atlantic states to the CFE Treaty as the "cornerstone of European security" proved to be remarkably strong and durable.

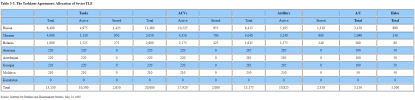

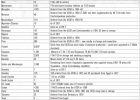

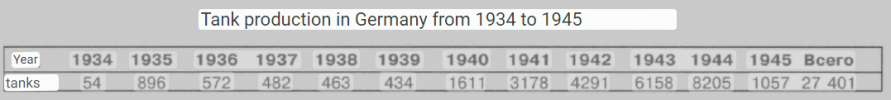

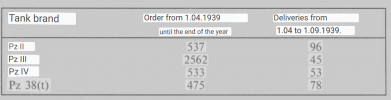

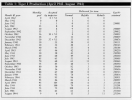

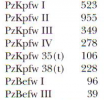

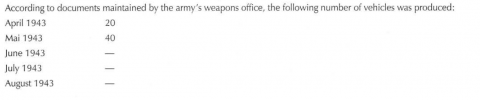

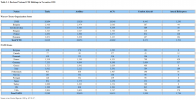

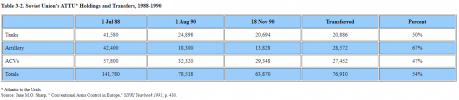

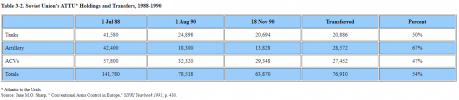

The first, and most serious, issue arose at the time of the CSCE/CFE Treaty summit in November 1990. On November 18, one day before treaty signing, representatives from each of the signatory states placed stacks of treaty-mandated data books on long rows of tables in the Hofburg Palace in Vienna. The books listed detailed information on force structure, force size, military units and organizations, and military weapons in the five treaty categories of armaments: tanks, artillery, armored personnel carriers, helicopters, and combat aircraft. Shortly thereafter, state delegates moved from table to table scooping up copies of these invaluable military force data. U.S. CFE Treaty Negotiator Lynn M. Hansen, who was in the Hofburg Palace that morning, characterized the exchange as having the "aura of a bazaar." He remembered military officers and specialists excited and buzzing at the opportunity to compare treaty declarations against current estimates.2 Within days, however, the atmosphere changed for the worse as serious questions arose about the Soviet Union's force data (see table 3-1).3

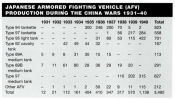

It appeared to many of the state delegates in Vienna that the Soviet Union had underrepresented its treaty holdings by a significant degree. In July 1988, when all the states had presented their force data to the negotiating teams, the Soviet Union had given out one set of data. Now in November 1990, at treaty signature, it had presented a much different set of data. When compared, there were major discrepancies. U.S. officials reported to President Bush that the Soviet discrepancy was between 20,000 and 40,000 items: 6,000 to 11,000 tanks, 12,000 armored fighting vehicles, 12,000 artillery pieces, and 3,000 combat aircraft.4 This was a serious discrepancy, one that clearly threatened ratification. Was there a Soviet explanation?

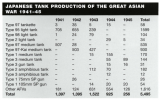

In Vienna, Soviet diplomats explained that during the two years of treaty negotiations, 1989-90, the Soviet High Command had conducted a large-scale operation that withdrew thousands of military personnel, weapons, and units from Central and Eastern Europe. It was this military equipment, they asserted, that accounted for the difference.5 They explained that in one category alone, tanks, the Soviet Army had destroyed, exported, or converted more than 4,000 items since 1989. The Soviet military had sent another 8,000 tanks to motor rifle and other divisions stationed in Asia, or to military storage depots located beyond the Ural Mountains. In addition, they pointed out that the Soviet military had sent thousands of items from other treaty-limited equipment (TLE) categories--artillery, armored combat vehicles (ACVs), and helicopters--to military depots and active units stationed beyond the Urals.6 The Ural Mountains were the CFE Treaty's easternmost boundary; military equipment located east of the Urals was not subject to any of the treaty's requirements. There would be no requirement for its inclusion in the initial data, for on-site inspection teams to count it, or for it to be reduced within a set period of time. Finally, the Soviet diplomats explained that since much of this equipment had been transferred from specialized combat support units, those units no longer held any TLE.7 Those units, by the treaty's inspection protocols, would not be objects of verification (OOVs). As a result, the Soviet Union's OOVs dropped from approximately 1,500 to fewer than 1,000.

Further, the Soviet diplomats asserted that this information should not have come as a surprise. In early October, Soviet General Mikhail A. Moiseyev, Chief of the Soviet General Staff, had announced the specific details of many of these force movements at a Pentagon press conference in Washington, D.C.8 Just four weeks before the Vienna meeting, Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze had sent a detailed letter on October 13, 1990, to U.S. Secretary of State James Baker listing the number and category of equipment removed from Central Europe to the east.9 But some Soviet officials had made statements that indicated a far different situation. In early October, Soviet Ambassador Oleg Grinevsky spoke informally with the other CFE Treaty diplomats in Vienna, stating that the USSR would have 1,600 OOVs at treaty signature, and approximately 1,500 OOVs at the end of the 40-month reduction phase.10 Therefore, when the Soviet Union revealed in Vienna, just one day before the official signing of the treaty in Paris, the scope of its unilateral military equipment relocation and the decrease in its inspectable sites, it surprised and disturbed many diplomats from the other CFE nations. At the very least, it raised serious questions of credibility.

Within a few weeks, diplomats linked these questions to other unilateral treaty-related actions by the Soviet Union. The Soviet High Command, according to the USSR's data books, had resubordinated three motor rifle divisions to naval infantry forces. In terms of CFE Treaty equipment, this meant they had transferred to the naval forces 120 tanks, 753 armored personnel vehicles, and 234 artillery pieces. The Soviet High Command also had established a new kind of naval unit, the coastal defense forces, and assigned to it 813 tanks, 972 ACVs, and 846 artillery pieces. In addition, the Strategic Rocket Forces received 1,791 ACVs.11 During treaty negotiations, delegates considered all this equipment to be a part of the USSR's CFE Treaty TLE ceilings, subject to reduction quotas and inspection protocols. In Vienna, Soviet diplomats argued that since the Soviet High Command had reassigned this equipment to naval units, which they asserted were not included in the treaty, the equipment would not be subject to treaty inspections or ceilings. Further, they asserted that the Strategic Rocket Forces' 1,791 ACVs should be classified as internal security equipment, again outside the treaty's quantitative provisions. Finally, the Soviet data omitted 18 PT-76 armored combat vehicles, which had belonged to the civil defense forces, from the TLE category of heavy armament combat vehicles. Neither in their data submission nor in subsequent discussions did the Soviets give any explanation for this omission.12

Despite these discrepancies, the treaty was signed on November 19, 1990. Nonetheless, four states--the United States, Germany, Canada, and Great Britain--raised specific questions about the Soviet data. The forum they used was the newly established CFE Treaty Joint Consultative Group (JCG).13 One of this group's responsibilities was to seek resolutions of ambiguities in data or differences of interpretation resulting from treaty implementation. Clearly, the dispute with the Soviet Union, a major signatory party, over its initial data submission fell within the scope of the JCG. Article V of the treaty, and a separate protocol, authorized and set forth the responsibilities and procedural rules governing this important joint treaty group. Consisting of representatives from every signatory state, the JCG was to meet in Vienna twice a year, with each session lasting four weeks. In fact, the initial issues were so contentious that the JCG met in nearly continuous monthly sessions beginning in late November 1990.

The state parties had 90 days--until February 15, 1991--to correct any discrepancies in their initial data and to respond to ambiguities. The United States, Great Britain, Germany, and Canada urged the Soviet Union to reconsider its initial submission. During this 90-day period, diplomats from the United States and several other NATO nations sought to use bilateral diplomacy to resolve the issue. Early in December, Ambassador R. James Woolsey, U.S. CFE Treaty Negotiator, Brigadier General Daniel W. Christman, USA, Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) representative, and a small team flew to Moscow to meet with Defense Minister Marshal Dmitriy Yazov, General Moiseyev, and other members of the Soviet Supreme High Command.14 Foreign Minister Shevardnadze was not present. Defense Minister Yazov refused categorically to consider any changes to the Soviet position on the former TLE equipment assigned to naval and civil defense units. That equipment, he asserted, might become part of a possible future treaty on conventional naval forces, but the Soviet military did not have to count it with the Soviet Union's TLE for the CFE Treaty. Ambassador Woolsey rejected Yazov's assertion out of hand. He regarded the Soviet defense minister's position as directly contravening the negotiated and signed treaty. An angry confrontation ensued. Woolsey told Yazov that the United States would accept the Soviet position "over my dead body!"15

This exchange hardened the impasse. At subsequent U.S.-USSR diplomatic meetings in Houston, Texas, and Brussels, Belgium, in December 1990 and January 1991, Soviet military leaders remained obdurate. Then, on February 14, 1991, the Soviet Union presented its updated treaty data to the JCG in Vienna. It retained every essential element under dispute--the exempted TLE reassigned to the coastal defense forces, naval infantry forces, Strategic Rocket Forces, and civil defense units. Given this fact, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker declared on the same day that President Bush would not submit the CFE Treaty to the U.S. Senate for ratification.16

It is interesting that in the midst of this frosty atmosphere, the diplomats resolved one issue: the 20,000-40,000 discrepancy in the Soviets' data. Analysis of two key documents supported the Soviet position. First, Soviet Minister Shevardnadze's letter to Secretary of State Baker, dated October 13, 1990, had contained specific figures on the Soviet forces and equipment in the treaty's zones as well as details on the TLE transfers from 1988 to 1990. Excerpted, the data revealed the following information:

Secretary Baker and General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had received these Soviet figures in late October. Then, three weeks later, the Soviets had presented these same figures in Vienna at the initial data exchange. Consequently, continued U.S. objections in the winter of 1990-91 stood on thin ice. The ice got even thinner in January 1991 when U.S. intelligence estimates confirmed that the Soviet Union's data discrepancy was not in the 20,000-40,000 range, but probably entailed 2,000-3,000 items.17 With this new estimate, the issue melted away, losing its power to influence treaty ratification.

What did not disappear, however, was the Soviet High Command's insistence on the legitimacy of resubordinating the three motorized rifle divisions to the naval infantry and the coastal defense forces. This position alone meant that on February 14, 1991, the date when the Soviet Union submitted its updated data, the CFE Treaty was at an impasse. Some believed that the Soviet High Command wanted to stop the CFE Treaty ratification process cold and substitute for the treaty a "status-quo" military relationship of the Soviet Union with Central and Western European nations.18 If this were true, the Soviet military's vision proved to be shortsighted in view of subsequent events.

In the spring and summer months of 1991, the Soviet Union's internal and external policies were subject to larger and more powerful events. In late February, a United Nations coalition, led by the United States, won a decisive victory in the Gulf War over Iraq, a former Soviet ally. Simultaneously, in late January and February, the people of the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania rebelled against Soviet imperialism.19 Following a brief, violent confrontation, they won recognition of their sovereignty from Moscow. Then, throughout April, May, and June, President Gorbachev and the Communist central government gradually lost power to Boris Yeltsin, Russian reformers, and nationalistic leaders in the republics. The Soviet High Command's desire to establish a Soviet-dominated imperial security system based on the military status quo became untenable as the Soviet Union unraveled both as an empire and a nation.

While the old system was untenable, it would take many months for the new reality to emerge. The Soviet Union remained a great military power and a major CFE Treaty state party. Following the Gulf War, President Bush began a series of arms control initiatives.20 He directed Secretary of State Baker to initiate diplomatic discussions with Soviet Foreign Minister Alexander A. Bessmertnykh. Baker focused on resolving both the CFE Treaty impasse and the outstanding issues of the still-unsigned Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START). In the White House, President Bush set up a small, high-level experts group on arms control to draft presidential letters and new treaty positions and to formulate immediate responses. Led by Arnold Kanter of the National Security Council, this four-person group worked closely with Secretary Baker, Ambassador Woolsey, CFE Treaty Negotiator Hansen, and the START Treaty negotiators. Initially there was little change. In March, Soviet Foreign Minister Bessmertnykh met with Secretary Baker in Moscow. He asked Baker to reconsider the United States' opposition to the Soviet High Command's resubordination of CFE TLE to naval and coastal defense units. Baker replied: "I don't know what there is to talk about. Twenty-two countries have signed this treaty, and only one has changed the rules."21

Next, President Bush wrote directly to President Gorbachev asking him to resolve the dispute on the reassignment of the military equipment. Secretary Baker made a direct appeal to Bessmertnykh in Russia in late April. Neither Bush's letter nor Baker's personal diplomacy had much effect. Then in late May a breakthrough occurred. President Gorbachev sent General Moiseyev to Washington for a two-day meeting with the president, senior military leaders, and treaty negotiators.22 He brought with him new proposals. General Moiseyev stated the Soviet Union's final position: all equipment in the Soviet naval infantry and coastal defense forces would remain in their units, but they would be counted against the USSR's overall CFE Treaty ceilings. The number of armored personnel vehicles assigned to the Strategic Rocket Forces (SRF) would be limited to 1,701, but they would not be counted against the Soviet Union's aggregate number of treaty ACVs. The naval forces would not be counted as OOVs, limiting the number of inspections the Soviets would be liable for, but these units would still be vulnerable to inspection under the challenge inspection provisions. More important, the naval forces equipment would be counted in Soviet TLE totals. The issue of armored personnel vehicles in the SRF was countered somewhat by the U.S. concern for the security of Soviet nuclear materials if the Soviet Union became less stable. After consideration, U.S. experts accepted the Soviet position. The next day General Moiseyev met with President Bush in the White House. According to a recent account, President Bush was insistent and very firm on the United States' commitment to the treaty and the consequences of any nation trying to back out at this late stage.23 General Moiseyev agreed, stating his support for President Gorbachev, perestroika, and arms control.

The CFE Treaty was multilateral, with 22 signatory nations; no one could deny, however, that bilateral negotiations had resolved this treaty impasse. The United States and the Soviet Union acted decisively, but bilaterally, in reaching these settlements. At times allies were informed; other times they were not. Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Germany complained that the United States and the USSR were settling multilateral treaty issues among themselves.24 Yet during months of turmoil and real uncertainty, U.S. and Soviet political leaders focused again and again on the CFE Treaty; their persistence produced results.

It was only a matter of weeks from the time of General Moiseyev's Washington visit in May 1991 to the USSR's formal declaration to all other treaty states in Vienna. In early June, Secretary Baker and Ambassador Woolsey flew to Moscow and met with Foreign Minister Bessmertnykh and Soviet CFE Treaty Negotiator Grinevsky. The result was a complex, three-part solution.25 First, France, as a CFE Treaty signatory state, would request that the Netherlands convene an extraordinary conference of state parties to the treaty at The Hague. Next, the Soviet Union, at that conference, would issue a legally binding statement explaining the obligations it would undertake "outside of the framework of the treaty" to account for its TLE holdings within the treaty's area of application. The Soviet Union would declare its willingness to limit the equipment in its naval infantry forces, coastal defense forces, and Strategic Rocket Forces to the exact number previously announced in Vienna. Then, they would declare that 40 months after entry into force, the USSR's maximum TLE holdings would include the total TLE assigned to the naval infantry forces, coastal defense forces, and Strategic Rocket Forces. This meant that the Soviet Union would reduce an equivalent number of TLE elsewhere to meet its maximum holdings. Specifically, the Soviets pledged to destroy or convert 933 tanks, 1,725 ACVs, and 1,080 artillery pieces. They would reduce one-half of the 933 tanks and 1,080 artillery pieces from forces within the ATTU and the other half from forces east of the Urals. The Soviets also stated that they would modify 753 of the 1,725 ACVs to become MTLB-AT types. These were "look-alikes" and thus, not limited by the treaty.26

The Soviets were adamant in their position that the coastal defense forces and naval infantry units were not OOVs and therefore not subject to declared site inspections. They agreed, however, that this equipment would be subject to challenge inspections. They also declared that they would limit the number of armored combat vehicles of the SRF, but that these limits would not count against the total number of ACVs allocated under the CFE Treaty to the Soviet Union. In response to the Soviet Union's statement, each of the other 21 states at the extraordinary conference would issue a statement accepting the Soviet Union's declaration as legally binding and the basis for proceeding toward ratification and implementation. When the extraordinary conference convened at The Hague on June 18, 1991, the respective ambassadors read their carefully crafted, legally binding statements into the record and, with no objections, the chairman accepted them as official treaty documents.27

On the issue of the Soviet military equipment positioned east of the Ural Mountains, the Soviet government presented a politically binding statement to the state delegates attending the CFE's Joint Consultative Group in Vienna. The Soviet Union pledged to destroy or convert to civilian use no fewer than 6,000 tanks, 1,500 ACVs, and 7,000 artillery pieces located beyond the Ural Mountains. They would reduce these items by November 1995 in such a way as to provide "sufficient visible evidence" of their destruction or their having been rendered militarily unsuitable. Essentially, the pledge meant that the Soviet Union would display this equipment so that treaty states could use satellite reconnaissance to monitor and confirm its reduction.28

Once these Soviet legal and political statements had been accepted as official treaty documents, most of the CFE Treaty signatory states turned to ratification. President Bush submitted the CFE Treaty to the U.S. Senate on July 9, 1991, stating, "The CFE Treaty is the most ambitious arms control agreement ever concluded."29 He declared that the treaty was in the "best interests of the United States" and that it was an important step in "defining the new security regime in Europe." Other states went through the ratification process as well. Czechoslovakia was the first nation to ratify the treaty and deposit the instruments of ratification in the treaty depository at The Hague. Other nations followed and by the end of 1991, 14 nations, including Hungary, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, United Kingdom, Poland, Germany, and the United States, had ratified the treaty. Before all the original 22 treaty signatories could complete the ratification process, however, three new developments influenced the treaty.

(jatkuu seuraavassa viestissä)

Chapter 3 - RATIFICATION DELAYED, EUROPE IN TURMOIL, SOVIET UNION IN REVOLUTION

As Europe entered the 1990s, it was in turmoil. From 1989 to 1992-coinciding with the years of the CFE Treaty's negotiation, ratification, and entry into force-nations on the European continent were experiencing their greatest changes since the end of World War II. There was the unification of Germany; the "velvet" political revolutions casting out Communist systems in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia; the bloody revolution in Romania; the continuous integration of the European Union; the recurrent economic and political crises in the Soviet Union presaging its collapse; the national independence movements in the former Soviet republics; and, running throughout, the large-scale military withdrawals from Central and Western Europe by the Soviet Union and the United States. Politically, diplomatically, and militarily, the European continent was in the midst of revolutionary changes. It was in this context that ratification and implementation of the CFE Treaty proceeded.

FROM TREATY SIGNATURE TO RATIFICATION

In constitutional governments, treaties require two acts for legitimacy: executive signature and legislative ratification. For the United States, President Bush signed the CFE Treaty in Paris on November 19, 1990. That same day, the leaders of 21 other NATO and Warsaw Pact nations signed the treaty. Ratification, however, took nearly two years. On October 30, 1992, just 20 days short of two full years, the final two states, Belarus and Kazakstan, ratified the treaty and deposited their instruments of ratification at The Hague in the Netherlands. Why did it take so long?

One CFE Treaty signatory state, the Soviet Union, was in such turmoil in 1991 and 1992 that its very existence was in question.1 When the USSR collapsed in late December 1991, its successor states had to form new governments, and those governments had to work out military and security relationships with Russia, the largest and most powerful of the former republics.

So great were the repercussions from the Soviet Union's internal difficulties that the CFE Treaty signatory states had to convene four separate extraordinary meetings to approve, authorize, and incorporate new statements, understandings, declarations, and agreements into the treaty regarding entitlements and obligations. In June 1991, the signatory states met at The Hague; in October 1991 they convened in Vienna; in June 1992 they met in Oslo; and, finally, in July 1992, they assembled just before the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) summit in Helsinki. At each of these meetings, the diplomats took up specific treaty issues for the group to resolve before the individual states would proceed with ratification and implementation. Every issue was a consequence of the Soviet Union's collapse as an empire. Throughout these extraordinary meetings across Europe, the commitment of the European and North Atlantic states to the CFE Treaty as the "cornerstone of European security" proved to be remarkably strong and durable.

THE FIRST CRISIS: SURPRISES AT THE DATA EXCHANGE

The first, and most serious, issue arose at the time of the CSCE/CFE Treaty summit in November 1990. On November 18, one day before treaty signing, representatives from each of the signatory states placed stacks of treaty-mandated data books on long rows of tables in the Hofburg Palace in Vienna. The books listed detailed information on force structure, force size, military units and organizations, and military weapons in the five treaty categories of armaments: tanks, artillery, armored personnel carriers, helicopters, and combat aircraft. Shortly thereafter, state delegates moved from table to table scooping up copies of these invaluable military force data. U.S. CFE Treaty Negotiator Lynn M. Hansen, who was in the Hofburg Palace that morning, characterized the exchange as having the "aura of a bazaar." He remembered military officers and specialists excited and buzzing at the opportunity to compare treaty declarations against current estimates.2 Within days, however, the atmosphere changed for the worse as serious questions arose about the Soviet Union's force data (see table 3-1).3

It appeared to many of the state delegates in Vienna that the Soviet Union had underrepresented its treaty holdings by a significant degree. In July 1988, when all the states had presented their force data to the negotiating teams, the Soviet Union had given out one set of data. Now in November 1990, at treaty signature, it had presented a much different set of data. When compared, there were major discrepancies. U.S. officials reported to President Bush that the Soviet discrepancy was between 20,000 and 40,000 items: 6,000 to 11,000 tanks, 12,000 armored fighting vehicles, 12,000 artillery pieces, and 3,000 combat aircraft.4 This was a serious discrepancy, one that clearly threatened ratification. Was there a Soviet explanation?

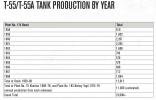

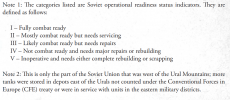

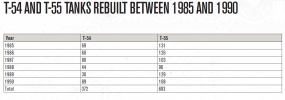

In Vienna, Soviet diplomats explained that during the two years of treaty negotiations, 1989-90, the Soviet High Command had conducted a large-scale operation that withdrew thousands of military personnel, weapons, and units from Central and Eastern Europe. It was this military equipment, they asserted, that accounted for the difference.5 They explained that in one category alone, tanks, the Soviet Army had destroyed, exported, or converted more than 4,000 items since 1989. The Soviet military had sent another 8,000 tanks to motor rifle and other divisions stationed in Asia, or to military storage depots located beyond the Ural Mountains. In addition, they pointed out that the Soviet military had sent thousands of items from other treaty-limited equipment (TLE) categories--artillery, armored combat vehicles (ACVs), and helicopters--to military depots and active units stationed beyond the Urals.6 The Ural Mountains were the CFE Treaty's easternmost boundary; military equipment located east of the Urals was not subject to any of the treaty's requirements. There would be no requirement for its inclusion in the initial data, for on-site inspection teams to count it, or for it to be reduced within a set period of time. Finally, the Soviet diplomats explained that since much of this equipment had been transferred from specialized combat support units, those units no longer held any TLE.7 Those units, by the treaty's inspection protocols, would not be objects of verification (OOVs). As a result, the Soviet Union's OOVs dropped from approximately 1,500 to fewer than 1,000.

Further, the Soviet diplomats asserted that this information should not have come as a surprise. In early October, Soviet General Mikhail A. Moiseyev, Chief of the Soviet General Staff, had announced the specific details of many of these force movements at a Pentagon press conference in Washington, D.C.8 Just four weeks before the Vienna meeting, Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze had sent a detailed letter on October 13, 1990, to U.S. Secretary of State James Baker listing the number and category of equipment removed from Central Europe to the east.9 But some Soviet officials had made statements that indicated a far different situation. In early October, Soviet Ambassador Oleg Grinevsky spoke informally with the other CFE Treaty diplomats in Vienna, stating that the USSR would have 1,600 OOVs at treaty signature, and approximately 1,500 OOVs at the end of the 40-month reduction phase.10 Therefore, when the Soviet Union revealed in Vienna, just one day before the official signing of the treaty in Paris, the scope of its unilateral military equipment relocation and the decrease in its inspectable sites, it surprised and disturbed many diplomats from the other CFE nations. At the very least, it raised serious questions of credibility.

Within a few weeks, diplomats linked these questions to other unilateral treaty-related actions by the Soviet Union. The Soviet High Command, according to the USSR's data books, had resubordinated three motor rifle divisions to naval infantry forces. In terms of CFE Treaty equipment, this meant they had transferred to the naval forces 120 tanks, 753 armored personnel vehicles, and 234 artillery pieces. The Soviet High Command also had established a new kind of naval unit, the coastal defense forces, and assigned to it 813 tanks, 972 ACVs, and 846 artillery pieces. In addition, the Strategic Rocket Forces received 1,791 ACVs.11 During treaty negotiations, delegates considered all this equipment to be a part of the USSR's CFE Treaty TLE ceilings, subject to reduction quotas and inspection protocols. In Vienna, Soviet diplomats argued that since the Soviet High Command had reassigned this equipment to naval units, which they asserted were not included in the treaty, the equipment would not be subject to treaty inspections or ceilings. Further, they asserted that the Strategic Rocket Forces' 1,791 ACVs should be classified as internal security equipment, again outside the treaty's quantitative provisions. Finally, the Soviet data omitted 18 PT-76 armored combat vehicles, which had belonged to the civil defense forces, from the TLE category of heavy armament combat vehicles. Neither in their data submission nor in subsequent discussions did the Soviets give any explanation for this omission.12

Despite these discrepancies, the treaty was signed on November 19, 1990. Nonetheless, four states--the United States, Germany, Canada, and Great Britain--raised specific questions about the Soviet data. The forum they used was the newly established CFE Treaty Joint Consultative Group (JCG).13 One of this group's responsibilities was to seek resolutions of ambiguities in data or differences of interpretation resulting from treaty implementation. Clearly, the dispute with the Soviet Union, a major signatory party, over its initial data submission fell within the scope of the JCG. Article V of the treaty, and a separate protocol, authorized and set forth the responsibilities and procedural rules governing this important joint treaty group. Consisting of representatives from every signatory state, the JCG was to meet in Vienna twice a year, with each session lasting four weeks. In fact, the initial issues were so contentious that the JCG met in nearly continuous monthly sessions beginning in late November 1990.

The state parties had 90 days--until February 15, 1991--to correct any discrepancies in their initial data and to respond to ambiguities. The United States, Great Britain, Germany, and Canada urged the Soviet Union to reconsider its initial submission. During this 90-day period, diplomats from the United States and several other NATO nations sought to use bilateral diplomacy to resolve the issue. Early in December, Ambassador R. James Woolsey, U.S. CFE Treaty Negotiator, Brigadier General Daniel W. Christman, USA, Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) representative, and a small team flew to Moscow to meet with Defense Minister Marshal Dmitriy Yazov, General Moiseyev, and other members of the Soviet Supreme High Command.14 Foreign Minister Shevardnadze was not present. Defense Minister Yazov refused categorically to consider any changes to the Soviet position on the former TLE equipment assigned to naval and civil defense units. That equipment, he asserted, might become part of a possible future treaty on conventional naval forces, but the Soviet military did not have to count it with the Soviet Union's TLE for the CFE Treaty. Ambassador Woolsey rejected Yazov's assertion out of hand. He regarded the Soviet defense minister's position as directly contravening the negotiated and signed treaty. An angry confrontation ensued. Woolsey told Yazov that the United States would accept the Soviet position "over my dead body!"15

This exchange hardened the impasse. At subsequent U.S.-USSR diplomatic meetings in Houston, Texas, and Brussels, Belgium, in December 1990 and January 1991, Soviet military leaders remained obdurate. Then, on February 14, 1991, the Soviet Union presented its updated treaty data to the JCG in Vienna. It retained every essential element under dispute--the exempted TLE reassigned to the coastal defense forces, naval infantry forces, Strategic Rocket Forces, and civil defense units. Given this fact, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker declared on the same day that President Bush would not submit the CFE Treaty to the U.S. Senate for ratification.16

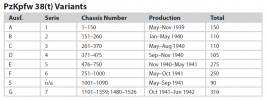

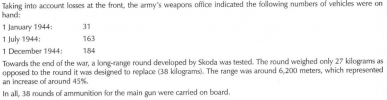

It is interesting that in the midst of this frosty atmosphere, the diplomats resolved one issue: the 20,000-40,000 discrepancy in the Soviets' data. Analysis of two key documents supported the Soviet position. First, Soviet Minister Shevardnadze's letter to Secretary of State Baker, dated October 13, 1990, had contained specific figures on the Soviet forces and equipment in the treaty's zones as well as details on the TLE transfers from 1988 to 1990. Excerpted, the data revealed the following information:

Secretary Baker and General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had received these Soviet figures in late October. Then, three weeks later, the Soviets had presented these same figures in Vienna at the initial data exchange. Consequently, continued U.S. objections in the winter of 1990-91 stood on thin ice. The ice got even thinner in January 1991 when U.S. intelligence estimates confirmed that the Soviet Union's data discrepancy was not in the 20,000-40,000 range, but probably entailed 2,000-3,000 items.17 With this new estimate, the issue melted away, losing its power to influence treaty ratification.

What did not disappear, however, was the Soviet High Command's insistence on the legitimacy of resubordinating the three motorized rifle divisions to the naval infantry and the coastal defense forces. This position alone meant that on February 14, 1991, the date when the Soviet Union submitted its updated data, the CFE Treaty was at an impasse. Some believed that the Soviet High Command wanted to stop the CFE Treaty ratification process cold and substitute for the treaty a "status-quo" military relationship of the Soviet Union with Central and Western European nations.18 If this were true, the Soviet military's vision proved to be shortsighted in view of subsequent events.

In the spring and summer months of 1991, the Soviet Union's internal and external policies were subject to larger and more powerful events. In late February, a United Nations coalition, led by the United States, won a decisive victory in the Gulf War over Iraq, a former Soviet ally. Simultaneously, in late January and February, the people of the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania rebelled against Soviet imperialism.19 Following a brief, violent confrontation, they won recognition of their sovereignty from Moscow. Then, throughout April, May, and June, President Gorbachev and the Communist central government gradually lost power to Boris Yeltsin, Russian reformers, and nationalistic leaders in the republics. The Soviet High Command's desire to establish a Soviet-dominated imperial security system based on the military status quo became untenable as the Soviet Union unraveled both as an empire and a nation.

While the old system was untenable, it would take many months for the new reality to emerge. The Soviet Union remained a great military power and a major CFE Treaty state party. Following the Gulf War, President Bush began a series of arms control initiatives.20 He directed Secretary of State Baker to initiate diplomatic discussions with Soviet Foreign Minister Alexander A. Bessmertnykh. Baker focused on resolving both the CFE Treaty impasse and the outstanding issues of the still-unsigned Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START). In the White House, President Bush set up a small, high-level experts group on arms control to draft presidential letters and new treaty positions and to formulate immediate responses. Led by Arnold Kanter of the National Security Council, this four-person group worked closely with Secretary Baker, Ambassador Woolsey, CFE Treaty Negotiator Hansen, and the START Treaty negotiators. Initially there was little change. In March, Soviet Foreign Minister Bessmertnykh met with Secretary Baker in Moscow. He asked Baker to reconsider the United States' opposition to the Soviet High Command's resubordination of CFE TLE to naval and coastal defense units. Baker replied: "I don't know what there is to talk about. Twenty-two countries have signed this treaty, and only one has changed the rules."21

Next, President Bush wrote directly to President Gorbachev asking him to resolve the dispute on the reassignment of the military equipment. Secretary Baker made a direct appeal to Bessmertnykh in Russia in late April. Neither Bush's letter nor Baker's personal diplomacy had much effect. Then in late May a breakthrough occurred. President Gorbachev sent General Moiseyev to Washington for a two-day meeting with the president, senior military leaders, and treaty negotiators.22 He brought with him new proposals. General Moiseyev stated the Soviet Union's final position: all equipment in the Soviet naval infantry and coastal defense forces would remain in their units, but they would be counted against the USSR's overall CFE Treaty ceilings. The number of armored personnel vehicles assigned to the Strategic Rocket Forces (SRF) would be limited to 1,701, but they would not be counted against the Soviet Union's aggregate number of treaty ACVs. The naval forces would not be counted as OOVs, limiting the number of inspections the Soviets would be liable for, but these units would still be vulnerable to inspection under the challenge inspection provisions. More important, the naval forces equipment would be counted in Soviet TLE totals. The issue of armored personnel vehicles in the SRF was countered somewhat by the U.S. concern for the security of Soviet nuclear materials if the Soviet Union became less stable. After consideration, U.S. experts accepted the Soviet position. The next day General Moiseyev met with President Bush in the White House. According to a recent account, President Bush was insistent and very firm on the United States' commitment to the treaty and the consequences of any nation trying to back out at this late stage.23 General Moiseyev agreed, stating his support for President Gorbachev, perestroika, and arms control.

The CFE Treaty was multilateral, with 22 signatory nations; no one could deny, however, that bilateral negotiations had resolved this treaty impasse. The United States and the Soviet Union acted decisively, but bilaterally, in reaching these settlements. At times allies were informed; other times they were not. Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Germany complained that the United States and the USSR were settling multilateral treaty issues among themselves.24 Yet during months of turmoil and real uncertainty, U.S. and Soviet political leaders focused again and again on the CFE Treaty; their persistence produced results.

It was only a matter of weeks from the time of General Moiseyev's Washington visit in May 1991 to the USSR's formal declaration to all other treaty states in Vienna. In early June, Secretary Baker and Ambassador Woolsey flew to Moscow and met with Foreign Minister Bessmertnykh and Soviet CFE Treaty Negotiator Grinevsky. The result was a complex, three-part solution.25 First, France, as a CFE Treaty signatory state, would request that the Netherlands convene an extraordinary conference of state parties to the treaty at The Hague. Next, the Soviet Union, at that conference, would issue a legally binding statement explaining the obligations it would undertake "outside of the framework of the treaty" to account for its TLE holdings within the treaty's area of application. The Soviet Union would declare its willingness to limit the equipment in its naval infantry forces, coastal defense forces, and Strategic Rocket Forces to the exact number previously announced in Vienna. Then, they would declare that 40 months after entry into force, the USSR's maximum TLE holdings would include the total TLE assigned to the naval infantry forces, coastal defense forces, and Strategic Rocket Forces. This meant that the Soviet Union would reduce an equivalent number of TLE elsewhere to meet its maximum holdings. Specifically, the Soviets pledged to destroy or convert 933 tanks, 1,725 ACVs, and 1,080 artillery pieces. They would reduce one-half of the 933 tanks and 1,080 artillery pieces from forces within the ATTU and the other half from forces east of the Urals. The Soviets also stated that they would modify 753 of the 1,725 ACVs to become MTLB-AT types. These were "look-alikes" and thus, not limited by the treaty.26

The Soviets were adamant in their position that the coastal defense forces and naval infantry units were not OOVs and therefore not subject to declared site inspections. They agreed, however, that this equipment would be subject to challenge inspections. They also declared that they would limit the number of armored combat vehicles of the SRF, but that these limits would not count against the total number of ACVs allocated under the CFE Treaty to the Soviet Union. In response to the Soviet Union's statement, each of the other 21 states at the extraordinary conference would issue a statement accepting the Soviet Union's declaration as legally binding and the basis for proceeding toward ratification and implementation. When the extraordinary conference convened at The Hague on June 18, 1991, the respective ambassadors read their carefully crafted, legally binding statements into the record and, with no objections, the chairman accepted them as official treaty documents.27

On the issue of the Soviet military equipment positioned east of the Ural Mountains, the Soviet government presented a politically binding statement to the state delegates attending the CFE's Joint Consultative Group in Vienna. The Soviet Union pledged to destroy or convert to civilian use no fewer than 6,000 tanks, 1,500 ACVs, and 7,000 artillery pieces located beyond the Ural Mountains. They would reduce these items by November 1995 in such a way as to provide "sufficient visible evidence" of their destruction or their having been rendered militarily unsuitable. Essentially, the pledge meant that the Soviet Union would display this equipment so that treaty states could use satellite reconnaissance to monitor and confirm its reduction.28

Once these Soviet legal and political statements had been accepted as official treaty documents, most of the CFE Treaty signatory states turned to ratification. President Bush submitted the CFE Treaty to the U.S. Senate on July 9, 1991, stating, "The CFE Treaty is the most ambitious arms control agreement ever concluded."29 He declared that the treaty was in the "best interests of the United States" and that it was an important step in "defining the new security regime in Europe." Other states went through the ratification process as well. Czechoslovakia was the first nation to ratify the treaty and deposit the instruments of ratification in the treaty depository at The Hague. Other nations followed and by the end of 1991, 14 nations, including Hungary, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, United Kingdom, Poland, Germany, and the United States, had ratified the treaty. Before all the original 22 treaty signatories could complete the ratification process, however, three new developments influenced the treaty.

(jatkuu seuraavassa viestissä)

Viimeksi muokattu: