Tuuli- ja aurinkovoima saattaa olla tuotettua kilowattituntia kohden edullista, mutta systeemitasolla maksettavaksi lankeavat epäsäännöllisen tuotannon katveet. Ilmaista lounasta ei ole tässäkään asiassa.

Tämä on itse asiassa helposti ymmärrettävissä. Ei-säädettävä tuotantokapasiteetti (=tuuli & aurinko) vaatii rinnalleen vastaavan määrän säädettävää tuotantokapasiteettia. Tämän kapasiteetin käyttöaste jää alhaiseksi jolloin tuotantokustannus yksikköä kohden nousee. Valtion tuilla rakennettu uusiutuva energia on pahentanut tilannetta, mutta perimmäinen syy on tuuli- ja aurinkovoiman ennustamattomuus, jonka vuoksi niiden markkinapenetraatio ei voi nousta kovin suureksi ilman huomattavia lisäkustannuksia.

Valtiotasolla tarkasteltuna on mielenkiintoista, että laajamittainen ydinvoiman tuotanto korreloi halvan sähkönhinnan kanssa, kun taas uusiutuvien kohdalla korrelaatio on käänteinen.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/michae...king-electricity-more-expensive/#1a2233d61dc6

If Solar And Wind Are So Cheap, Why Are They Making Electricity So Expensive?

Michael Shellenberger

Michael Shellenberger Contributor

Apr 23, 2018, 08:09pm

#Economy

Clipper yacht Liverpool 2018 passes the Burbo Bank Wind Farm on August 14, 2017, off Liverpool, England. (Photo by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Over the last year, the media have published

story after

story after

story about the declining price of solar panels and wind turbines.

People who read these stories are understandably left with the impression that the more solar and wind energy we produce, the lower electricity prices will become.

And yet that’s not what’s happening. In fact, it’s the opposite.

Between 2009 and 2017, the price of solar panels per watt

declined by 75 percent while the price of wind turbines per watt

declined by 50 percent.

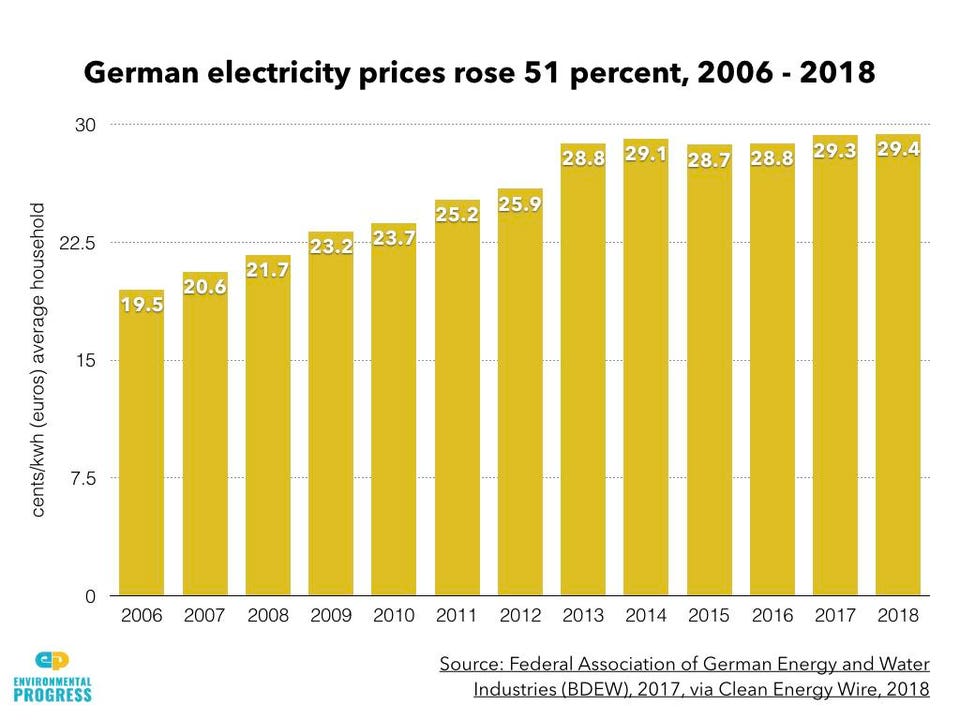

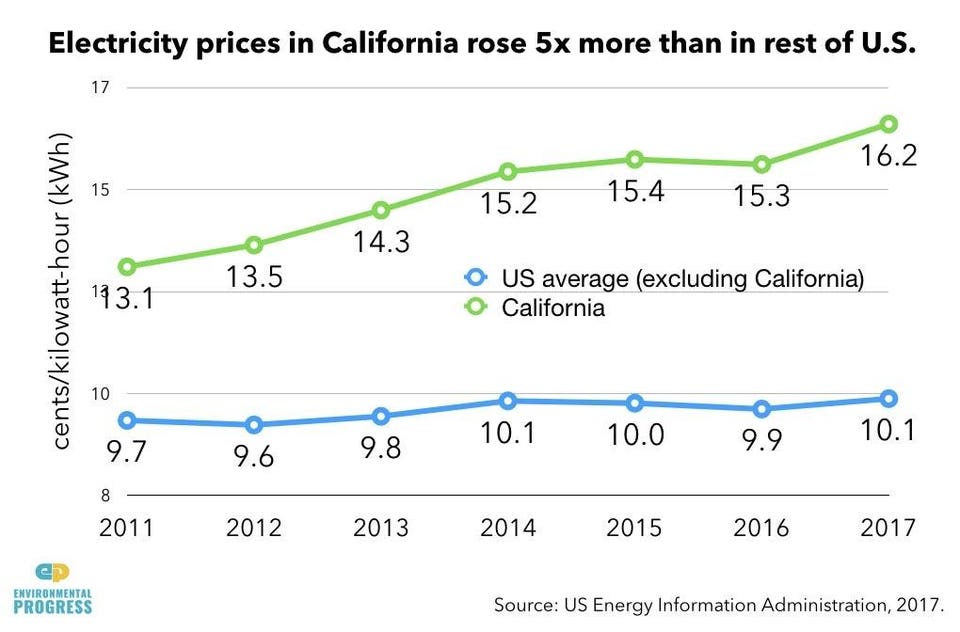

And yet — during the same period — the price of electricity in places that deployed significant quantities of renewables increased dramatically.

Electricity prices increased by:

What gives? If solar panels and wind turbines became so much cheaper, why did the price of electricity

rise instead of

decline?

EP

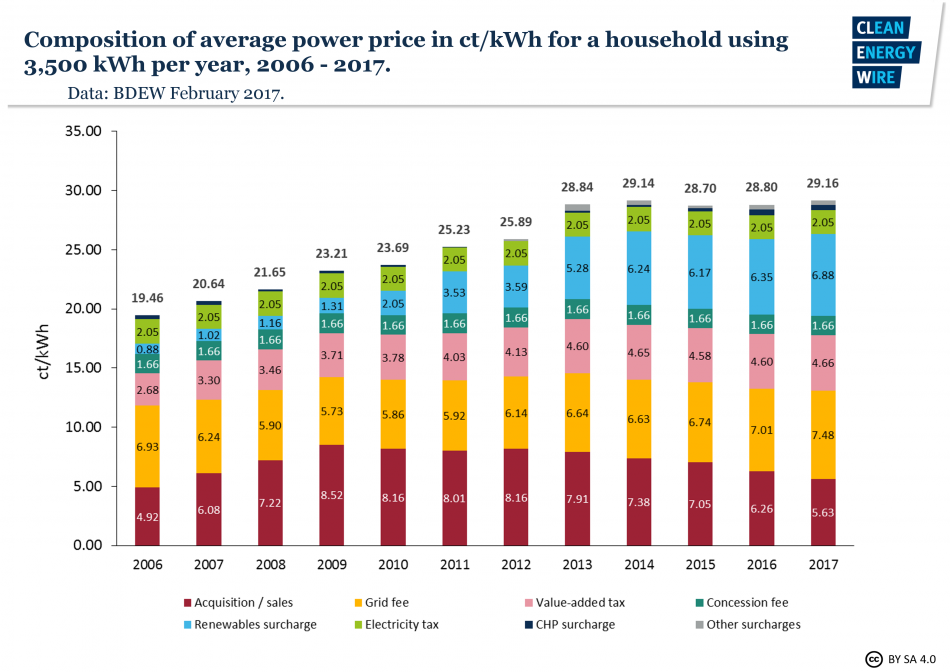

Electricity prices increased by 51 percent in Germany during its expansion of solar and wind energy.

One hypothesis might be that while electricity from solar and wind became cheaper, other energy sources like coal, nuclear, and natural gas became more expensive, eliminating any savings, and raising the overall price of electricity.

But, again, that’s not what happened.

The price of natural gas

declined by 72 percent in the U.S. between 2009 and 2016 due to the fracking revolution. In Europe, natural gas prices

dropped by a little less than half over the same period.

The price of nuclear and coal in those place during the same period was mostly flat.

EP

Electricity prices increased 24 percent in California during its solar energy build-out from 2011 to 2017.

Another hypothesis might be that the closure of nuclear plants resulted in higher energy prices.

Evidence for this hypothesis comes from the fact that nuclear energy leaders Illinois, France, Sweden and South Korea enjoy some of the cheapest electricity in the world.

Since 2010, California closed one nuclear plant (2,140 MW installed capacity) while Germany closed 5 nuclear plants and 4 other reactors at currently-operating plants (10,980 MW in total).

Electricity in Illinois is 42 percent cheaper than electricity in California while electricity in France is 45 percent cheaper than electricity in Germany.

But this hypothesis is undermined by the fact that the price of the main replacement fuels, natural gas and coal, remained low, despite increased demand for those two fuels in California and Germany.

That leaves us with solar and wind as the key suspects behind higher electricity prices. But why would

cheaper solar panels and wind turbines make electricity more

expensive?

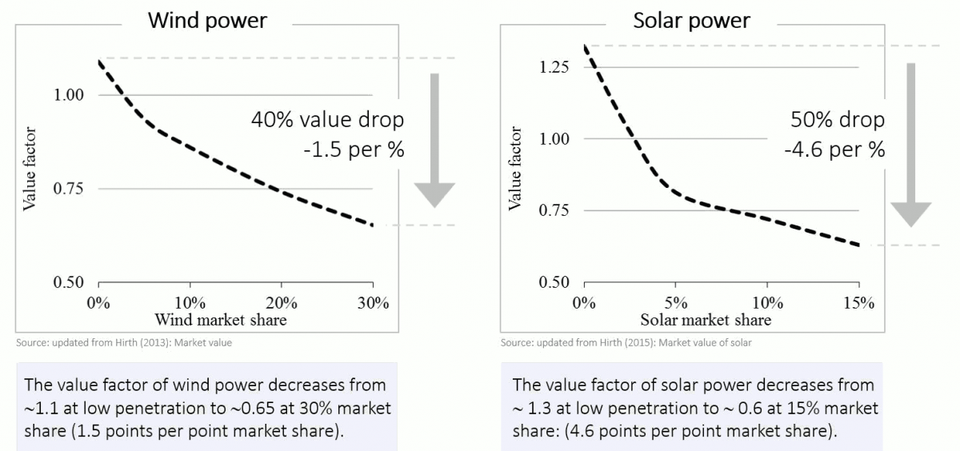

The main reason appears to have been predicted by a young German economist in 2013.

In a paper for

Energy Policy, Leon Hirth estimated that the economic value of wind and solar would decline significantly as they become a larger part of electricity supply.

The reason? Their fundamentally unreliable nature. Both solar and wind produce too much energy when societies don’t need it, and not enough when they do.

Solar and wind thus require that natural gas plants, hydro-electric dams, batteries or some other form of reliable power be ready at a moment’s notice to start churning out electricity when the wind stops blowing and the sun stops shining.

And unreliability requires solar- and/or wind-heavy places like Germany, California and Denmark to

pay neighboring nations or states to take their solar and wind energy when they are producing too much of it.

Hirth predicted that the economic value of wind on the European grid would decline 40 percent once it becomes 30 percent of electricity while the value of solar would drop by 50 percent when it got to just 15 percent.

EP

Hirth predicted that the economic value of wind would decline 40% once it reached 30% of electricity, and that the value of solar would drop by 50% when it reached 15% of electricity.

In 2017, the share of electricity coming from wind and solar was 53 percent in Denmark, 26 percent in Germany, and 23 percent in California. Denmark and Germany have the

first and second most expensive electricity in Europe.

By reporting on the declining costs of solar panels and wind turbines but not on how they increase electricity prices, journalists are — intentionally or unintentionally — misleading policymakers and the public about those two technologies.

The Los Angeles Times last year

reported that California’s electricity prices were rising, but failed to connect the price rise to renewables,

provoking a sharp rebuttal from UC Berkeley economist James Bushnell.

“The story of how California’s electric system got to its current state is a long and gory one,” Bushnell wrote, but “the dominant policy driver in the electricity sector has unquestionably been a focus on developing renewable sources of electricity generation.”

Part of the problem is that many reporters don’t understand electricity. They think of electricity as a commodity when it is, in fact, a service — like eating at a restaurant.

The price we pay for the luxury of eating out isn’t just the cost of the ingredients

most of which which, like solar panels and wind turbines, have

declined for decades.

Rather, the price of services like eating out and electricity reflect the cost not only of a few ingredients but also their preparation and delivery.

This is a problem of bias, not just energy illiteracy. Normally skeptical journalists routinely give renewables a pass. The reason isn’t because they don’t know how to report critically on energy — they do regularly when it comes to non-renewable energy sources — but rather because they don’t want to.

That could — and should — change. Reporters have an obligation to report accurately and fairly on all issues they cover, especially ones as important as energy and the environment.

A good start would be for them to investigate why, if solar and wind are so cheap, they are making electricity so expensive.