Over the past week, Canadians have been bombarded by claims about the cost and suitability of the F-35 aircraft and its various competitors. If the public is to make a decision, they deserve accurate, factual information to base it on. Many have touted the Boeing F/A-18E Super Hornet as the lowest-cost alternative to the F-35. However, to this date, there has not been an accurate comparison of the costs and capabilities published.

To start, it is important to understand that, much like an onion’s layers, there are different levels of cost. The most straightforward is the “flyaway” cost, which only includes the airframe, engine and avionics. This generally accounts for 75 per cent of the acquisition expenditure. The commonly cited $65 million price for the Super Hornet refers to its flyaway cost in 2012 U.S. dollars. This is a misleading comparison with the F-35’s flyaway and requires unpacking.

First, it is important to note that all fiscal figures are in 2012 U.S. Dollars, to eliminate inflation and exchange-rate variances. The last reliable cost data for the F/A-18E is from 2013, as the U.S. has only procured the electronic warfare variant (EA-18G) since then. Congressional reporting stated each aircraft’s cost as $62 million, but this has increased since. Boeing has cut the Super Hornet’s production rate from three aircraft to two, and it is currently slated to cease production in 2017. Consequently, its flyaway cost could be as high as $72 million.

Moreover, the Super Hornet’s flyaway price does not include several essential elements, such as sensor pods and external fuel tanks. These are all considered basic equipment for even our current CF-18s and the average cost for a set is $6.9 million. Finally, Canada would incur a $6.1 million Foreign Military Sales (FMS) charge on each aircraft. Added together, the Super Hornet’s true cost is between $75 million and $85 million.

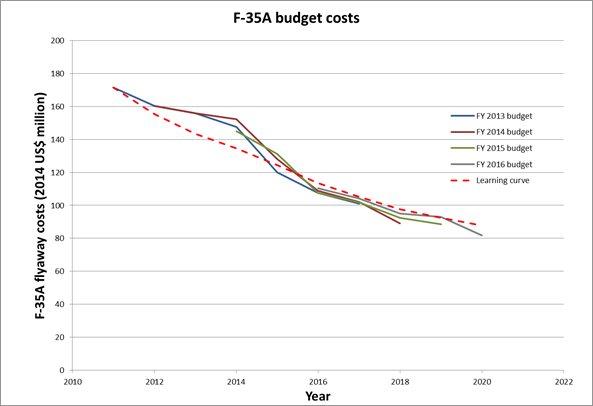

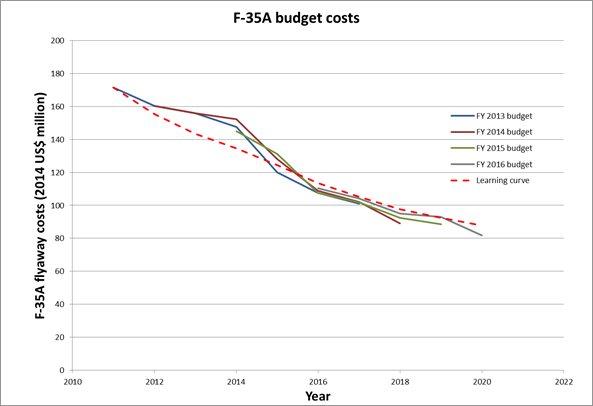

The F-35’s flyaway cost is estimated to be approximately $77 million for an aircraft delivered in or after 2020 (the price for the bulk of Canada’s purchases), not $175 million as claimed. There is high confidence in these figures. The Join Strike Fighter (JSF) program has met its acquisition cost targets for the past five years, according to U.S. Congress documentation. This is partly due to large economies of scale. In the next three years, as many F-35s will be produced as all of its competitors combined; or one aircraft every four days in 2018.

The F-35 is also not subject to the same secondary costs as the Super Hornet. It carries all of its sensors and fuel internally and does not require external pods. Finally, as a JSF Partner Nation, Canada is not subject to FMS fees. Thus a true apples-to-apples comparison sees the F-35 at around $77 million and the Super Hornet at $75 million to $85 million. Other alternatives have been cited for even higher costs. Accordingly, no significant acquisition savings can be found by selecting another aircraft.

The life-cycle accounting and operational considerations tells a similar story. The largest cost driver for operations is personnel salaries and fuel costs, which are roughly equivalent for the various competitors. The United States military believes that any cost variance with the F-35 will be offset by lower sortie requirements to maintain readiness and conduct operations, due to new simulator technologies and advanced capabilities. This efficiency can be understood in a comparison with the Super Hornet.

Last year, a U.S. government report stated: “there are current, more stressing threat environments in which the (Super Hornet) remains not operationally effective.” CF-18 pilots participating in Operation Reassurance were exposed to those very threats while supporting NATO allies from Russian aggression. In order to remain viable, the F/A-18E must operate in conjunction with an EA-18G to suppress any threats. This requires the purchase and operation of a second, more costly version of the Super Hornet, where a single F-35 may have sufficed.

This also illustrates the serious long-term risk involved with selecting a more limited aircraft. The CF-18 has been among the most active and popular military instrument in the past 25 years, with operations in the Gulf War, Balkans, Kosovo, Libya, Eastern Europe and Iraq. Thus, limiting the replacements’ capability would mark a radical reorientation of Canada’s foreign policy for the next 30 years and constrain a future leader’s options, perhaps at a time of national crisis.

Finally, a competition would be a costly and largely pointless process. Based on previous experiences and the complexity of fighter capabilities, a proper competition will require 200 or more staff members working for at least three years. Their salaries alone would cost Canada at least $70 million, with the outcome likely to be the reselection of the F-35. Nor will a competition result in a “better deal”: U.S. law prevents American manufacturers from selling such equipment for lower than what the U.S. government pays.

After analyzing the available information detailed above, it is clear that cancelling the F-35 procurement will not result in tens of billions of dollars saved, nor serve any of Canada’s longstanding interests. The men and women who will operate Canada’s future fighter deserve better.

...

...