Muistan VLS:n alkuaikoina joskus ihmetelleeni miten siilopaketissa voi olla 29 rööriä, kun ei ihan mene millään jakolaskulla tasan. Aika simppeli tuokin ratkaisu lopulta oli. Ei ollutkaan korkeampaa matematiikkaa.Ja myös US NAVY on Strikedownista luopunut DDG-78:n (1999) jälkeen. Uudemmat Burket ova isommalla ohjusmäärällä ilman nosturia.

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Merivoimien kehitysnäkymät

- Viestiketjun aloittaja Museo

- Aloitus PVM

Mikfin70

Ylipäällikkö

Taitavat hankkia K9 myös merivoimien tarpeisiin. 2000-luvun alun 155-hankkeessa tämä asia oli ensimmäistä kertaa esillä.

Taitavat hankkia K9 myös merivoimien tarpeisiin. 2000-luvun alun 155-hankkeessa tämä asia oli ensimmäistä kertaa esillä.

Identtinen alusta maavoimien kanssa toisi varmasti synergiaetuja operoinnin näkökulmasta ja helpottaisi varmasti käyttöönottoakin, kun kyseessä olisi olemassoleva järjestelmä.

Toisaalta tulee mieleen, että pyöräalusta olisi vikkelämpi liikumaan ja reagoimaan muuttuviin tilanteisiin. Logistinen jalanjälkikin on pienempi. Rannikolta löytyy kuitenkin lähtökohtaisesti aika kattava tieverkosto.

Archer.Identtinen alusta maavoimien kanssa toisi varmasti synergiaetuja operoinnin näkökulmasta ja helpottaisi varmasti käyttöönottoakin, kun kyseessä olisi olemassoleva järjestelmä.

Toisaalta tulee mieleen, että pyöräalusta olisi vikkelämpi liikumaan ja reagoimaan muuttuviin tilanteisiin. Logistinen jalanjälkikin on pienempi. Rannikolta löytyy kuitenkin lähtökohtaisesti aika kattava tieverkosto.

Toivottavasti rannalle saadaan oma tuliyksikkö, tai pari. Alkuperäiset kaavailuthan olivat sen suuntaisia, että merivoimille hankitaan ainoastaan ampumatarvikkeita ja tykit lainataan tarvittaessa maavoimilta. Pidän tuota mallia hieman riskialttiina, kun tehtävät ovat potentiaalisesti aikakriittisiä. Samalla tulisi korjattua rannikkojoukoilta nykyisellään puuttuva epäsuora tulituki.Taitavat hankkia K9 myös merivoimien tarpeisiin. 2000-luvun alun 155-hankkeessa tämä asia oli ensimmäistä kertaa esillä.

Mites toi NLOS Spike? Meneekö liian kalliiksi ja hankalaksi? Uusimmassa generaatiossa 50km kantama, sopii nykyisten rannikko-ohjusten kanssa samaan perheeseen, liikuteltavissa maalla sekä veneellä, voi toimia vaikka turvalta, jehusta tai epäonnekkaan rannarin kannosta jostain mäkiluodosta. SPIKE järjestelmä käytössä myös maavoimilla. Uskoakseni täyttäisi hyvin kaikki annetut vaatimukset ja olisi vähintäänkin erilainen lähestymiskulma kuin merivoimien omat Thunderit.

Osassa tehtäviä parempi kuin K9 ja osaan ei sovi ollenkaan. Tykki on monella tapaa monipuolisempi väline. Riippuu siis painotuksista, eikä voi sanoa että A on yksiselitteisesti parempi kuin B.Mites toi NLOS Spike? Meneekö liian kalliiksi ja hankalaksi? Uusimmassa generaatiossa 50km kantama, sopii nykyisten rannikko-ohjusten kanssa samaan perheeseen, liikuteltavissa maalla sekä veneellä, voi toimia vaikka turvalta, jehusta tai epäonnekkaan rannarin kannosta jostain mäkiluodosta. SPIKE järjestelmä käytössä myös maavoimilla. Uskoakseni täyttäisi hyvin kaikki annetut vaatimukset ja olisi vähintäänkin erilainen lähestymiskulma kuin merivoimien omat Thunderit.

Mites toi NLOS Spike? Meneekö liian kalliiksi ja hankalaksi? Uusimmassa generaatiossa 50km kantama, sopii nykyisten rannikko-ohjusten kanssa samaan perheeseen, liikuteltavissa maalla sekä veneellä, voi toimia vaikka turvalta, jehusta tai epäonnekkaan rannarin kannosta jostain mäkiluodosta. SPIKE järjestelmä käytössä myös maavoimilla. Uskoakseni täyttäisi hyvin kaikki annetut vaatimukset ja olisi vähintäänkin erilainen lähestymiskulma kuin merivoimien omat Thunderit.

Tykkejä minäkin suosisin, mutta Spike NLOS olisi sellainen järjestelmä jonka hankkisin jokatapauksessa joko tuohon tarkoitukseen tai sitten muusta syystä. Joskin nykyään noita kamikaze lennokkeja on saatavilla muitakin, joskaan ei taida olla noin pitkällä kantamalla.

fulcrum

Greatest Leader

Silloin kun amerikkalaiset tositilanteessa tällaisia maaleja ampuivat (tosin Ticonderogalla) niin meni vähän mönkään. Miniveneisiin ei juuri osuttu, mutta matkustajasuihkari kyllä ammuttiin alas.Ei ole varmaa, onko pöntöissä yleensäkään mitään ohjuksia. Voi olla ihan tyhjät kanisterit vain.

Muutenkin tuollaiselle viritykselle lähinnä nauretaan.

Millä järjestelmällä ohjukset laukaistaan? Miten maali otetaan seurantaan (tutka on pönttöjen välissä eikä näe kuin muutaman asteen sektorin keulaan)? Millaisia viestijärjestelmiä veneessä on (ei näy sen kummemmin VHF/UHF-alueen antenneja kuin HF-antenniakaan)?

Tiedättekö mitä, ihmiset? Arleigh Burke-luokan tai Type-45 -hävittäjien päälliköt oikein odottavat kohtaamista taistelutilanteessa noiden kanssa. Saa miehistöt hyvää harjoitusta liikkuvaan maaliin...

Enempi tuollaiset veneet on tarkoitettu harmaan vaiheen häirintään ja härnäämiseen. Ja jo tieto siitä että joissain pikaveneissä on ohjuksia voi saada vastapuolen tuhlaamaan ohjuksia ja aikaa toissijaisiin kohteisiin.

Huhta

Greatest Leader

Taitavat hankkia K9 myös merivoimien tarpeisiin. 2000-luvun alun 155-hankkeessa tämä asia oli ensimmäistä kertaa esillä.

Mites tuo taulukon 8. kohta? Alle 50-kilometrin kantamalla varustetut järjestelmät kyettävät integroimaan kevyelle ajoneuvoalustalle tai alukselle... K9 ei varmaan ihan Jehuun sovi?

Taulukon 15. kohta (ei ihmisille eikä ympäristölle vaarallisia aineita) ei myöskään taida sopia K9:ään. Eikös K9:ssä ole moottoriöljyä? Sitä kun vuotaa kunnossapidon yhteydessä, niin se on ympäristölle vaarallista! Vesialueilla varsinkin!

Mites toi NLOS Spike? Meneekö liian kalliiksi ja hankalaksi? Uusimmassa generaatiossa 50km kantama, sopii nykyisten rannikko-ohjusten kanssa samaan perheeseen, liikuteltavissa maalla sekä veneellä, voi toimia vaikka turvalta, jehusta tai epäonnekkaan rannarin kannosta jostain mäkiluodosta. SPIKE järjestelmä käytössä myös maavoimilla. Uskoakseni täyttäisi hyvin kaikki annetut vaatimukset ja olisi vähintäänkin erilainen lähestymiskulma kuin merivoimien omat Thunderit.

Siellähän oli 100x100m aluemaaliin vaikuttaminen vaatimuksena. Aika hankala nähdä millä vehkeellä kaikki edellinen täytetään, ellei se ole suurehko drone.

fulcrum

Greatest Leader

Toivottavasti rannalle saadaan oma tuliyksikkö, tai pari. Alkuperäiset kaavailuthan olivat sen suuntaisia, että merivoimille hankitaan ainoastaan ampumatarvikkeita ja tykit lainataan tarvittaessa maavoimilta. Pidän tuota mallia hieman riskialttiina, kun tehtävät ovat potentiaalisesti aikakriittisiä. Samalla tulisi korjattua rannikkojoukoilta nykyisellään puuttuva epäsuora tulituki.

Samaa mieltä, en pidä ollenkaan sellaisesta ajatuksesta että maavoimat vippaa meripuolustukselle pari patteria sitten kun maihinnousulaivasto on havaittu avomerellä. Rannikkötykistön merkitys viimeiset, noh, 80 vuotta on ollut se että se on korkeassa valmiudessa ja estää ettei aivan takki auki yllättäen seilata pääkaupungin torinrantaan. Ei sellaisessa tilanteessa kerkiä rustaamaan mitään alistuspyyntölomakkeita. Aseiden ja miehistöjen on oltava paikan päällä ja valmiina. Se oli muuten yksi kiinteän rannikkotykistön 'metahyöty', sitä ei voi laittaa johonkin Kainuuseen varastoon odottelemaan aikoja parempia, vaan se tekee vain sitä mihin se on tarkoitettu.

Mites toi NLOS Spike? Meneekö liian kalliiksi ja hankalaksi? Uusimmassa generaatiossa 50km kantama, sopii nykyisten rannikko-ohjusten kanssa samaan perheeseen, liikuteltavissa maalla sekä veneellä, voi toimia vaikka turvalta, jehusta tai epäonnekkaan rannarin kannosta jostain mäkiluodosta. SPIKE järjestelmä käytössä myös maavoimilla. Uskoakseni täyttäisi hyvin kaikki annetut vaatimukset ja olisi vähintäänkin erilainen lähestymiskulma kuin merivoimien omat Thunderit.

Vaatimuksissa mainittu aluemaaleihin vaikutus ehkei ole Spiken vahvinta osaamista? Aika selvästi tuossa haetaan jonkunlaista tykkijärjestelmää, vähän jätetty ovi auki muille ratkaisuille jos sieltä jotain löytyisi.

Olis ja muutenkin meillä olisi tarve pyöräalustaiselle tykille.Katso liite: 76105

Onhan sitä markkinoilla vaikka millaista. Ois aika ketterä ajella hanko-hamina väliä tai saariston rengastietä

Huhta

Greatest Leader

Käytännössä ohjus ja tykistöammus tässä vääntää kättä. Ohjuksella saa vaikutuksen 100x100m kuorma-ohjuksella

Ohjus ja tykistöammus... miten olisi tykistöohjus, MLRS:n PrSM? Aluemaaliin tepsii varmasti ja miten minulla on muistikuva, että siihen on kaavailtu kykyä vaikuttaa myös liikkuviin merimaaleihin?

Huhta

Greatest Leader

Army preps for key tests of seeker capable of attacking maritime targets

A captive-carry test for the multimode seeker, that will be integrated into the U.S. Army's Precision Strike Munition, is coming soon, as the service looks to find ways to speed up mating the seeker into the new long-range missile.

Army preps for key tests of seeker capable of attacking maritime targets

By Jen Judson

Jan 20, 2021

Lockheed Martin's PrSM missile was tested for a third time at White Sands Missile Range, in New Mexico, on April 30, 2020. (Lockheed Martin)

WASHINGTON — The Army is preparing for key tests of a multimode seeker for munitions that will be capable of attacking maritime targets, but current funding will prevent a faster timeline to integrate it into the Army’s future long-range missile, according to Brig. Gen. John Rafferty, who is in charge of the service’s long-range precision fires modernization efforts.

The Precision Strike Munition (PrSM) is on track for initial fielding in 2023, but the in-development multimode seeker, known as the Land-Based Anti-Ship Missile (LBASM), will be integrated into the capability at a later date.

The Army had hoped to accelerate the integration of the LBASM seeker in order to get after maritime and emitting integrated air defense system targets by hanging onto funding made available when one of the two vendors with funding to competitively develop PrSM made an early exit.

Lockheed Martin has stayed on as the sole developer of the PrSM missile after Raytheon ducked out before it’s first test shot in March 2020.

But the fiscal 2021 spending bill did not provide enough funding to move quicker, Rafferty told Defense News in a Jan. 14 interview.

While the Army won’t be moving faster to integrate the seeker, the service is heading into a February captive-carry test of the LBASM seeker at White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, Rafferty said.

Following that test, the Army will put the seeker inside a surrogate system to begin to refine its performance in a high-speed missile, in order to reduce the risk for integration into PrSM.

“It won’t fly as fast or as high or as far [as PrSM] but it’s the beginning of introducing it to that violent flight environment with the thermal challenges associated with high speed,” Rafferty said. “We’re not going to have the PrSM missiles yet to put the seeker into, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have to continue to develop the seeker and be ready when the resources are there.”

If the funding had lined up, the Army had hoped to deliver an urgent materiel release capability of the integrated seeker into PrSM in 2025. “So that is no longer possible,” he said. But Rafferty said he did not believe the integration would fall too far behind, adding it was still “in the realm of the possible” to get the seeker into PrSM by late 2026.

The disadvantages of going slower are “relatively minor,” Rafferty said, because the Army is racing to field a mid-range missile capable of getting after maritime targets by 2023.

in September, Defense News broke the news the Army was pursuing the mid-range capability, and the service has already awarded a contract to Lockheed Martin to take the Navy’s Raytheon-built SM-6 and Tomahawk missiles and put together a prototype that consists of launchers, missiles and a battery operations center.

Yet, the service will only buy a small number of that capability to fill the gap between the PrSM missile and hypersonic capability also under development.

“We’re going to pursue this medium-range capability, absolutely,” Rafferty said. “But maritime and medium-range capabilities, the bulk of it in the Army, will always come from the [High Mobility Artillery Rocket System] and the [Multiple Launch Rocket System] fleets. We have hundreds of those launchers, they’re survivable, they’re mobile, they’re dependable. They have high operational readiness rates and it uses our existing comms infrastructure, existing cyber support and fire direction systems.”

PrSM is designed to be launched from those systems, giving the units much longer-range capability.

While the Army figures out if it can come up with another way to integrate the seeker into PrSM faster, Rafferty said the service also saw “promising,” initial results from advanced propulsion work toward the end of 2020.

The advanced propulsion work will feed into efforts to further extend the range of the PrSM missile beyond 499 kilometers, now that it is no longer bound to that distance following the U.S. withdraw in the summer of 2019 from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. That agreement between the U.S. and Russia prohibited all nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.

The program has shared a proposed timeline for an extended-range PrSM with Army Futures Command leadership, but since it’s being reviewed, the schedule could not be detailed, Rafferty said.

The Army is also planning a 400 kilometer shot for PrSM at White Sands in April and will conduct a max range shot beyond 500 kilometers out at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, which has a test range capable of long-range missile shots, in August.

PrSM will also have a role to play in this year’s Project Convergence, which had its inaugural run at Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona, in September, and will be a yearly exercise to help give the service fidelity in terms of how its capabilities are meeting the needs of multidomain operations against anticipated threats.

Huhta

Greatest Leader

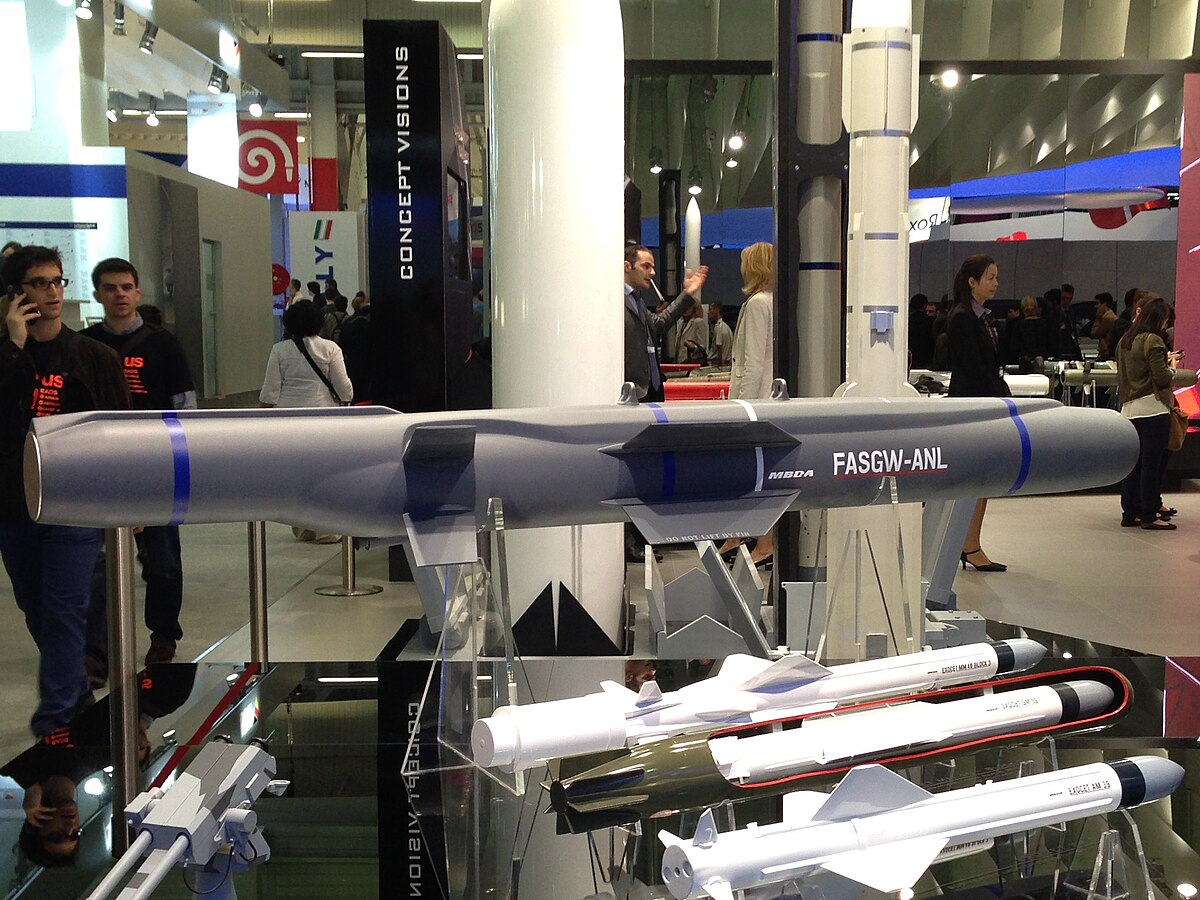

Oma lempilapseni on toki brittiläis-ranskalainen Sea Venom. Hakeutuminen INS ja IIR, joko itsenäisesti tai operaattorin ohjauksessa. Taistelukärki 30 kg, eli riittänee jollakin tasolla aluemaaliinkin. Kysymysmerkkinä lähinnä hinta.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org