The F-35A CTOL

F-35A, doors open

(click to view full)

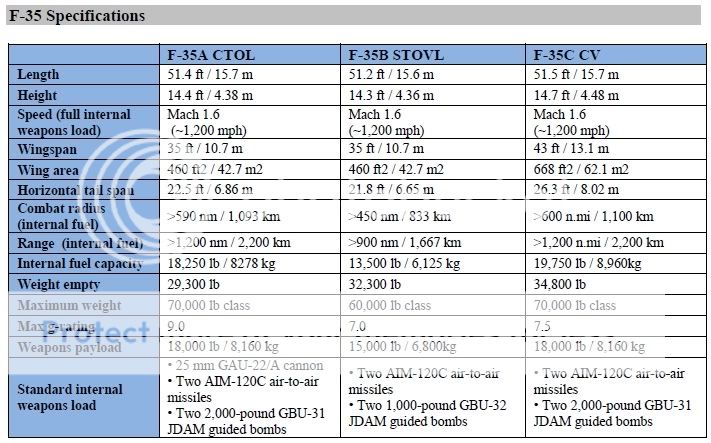

The F-35A is sometimes called the CTOL (Conventional Take-Off and Landing) version. It’s the USAF’s version, and is expected to make up most of the plane’s export orders.

It’s also expected to be the least expensive F-35,

in part because it will have the largest production run. The USAF currently estimates its average flyaway cost after 2017 at $108.3 million, but early production models ordered in FY 2012 will cost over $150 million.

Its main difference from other versions is its wider 9g maneuverability limits, though its air-air combat flight benchmarks are only

on par with the F-16 . Canard equipped “4+ generation” adversaries like the Eurofighter, and thrust-vectored fighters like the F-22A, MiG-35, SU-35, etc., will still enjoy certain kinetic advantages. The F-35 hopes to mitigate them using its improved stealth to shrink detection ranges, the lack of drag from weapons in its internal bays, and its current electronic superiority.

The second major physical difference between the F-35A and the rest of the Lightning family is its internal 25mm cannon, instead of using a weapons station for a semi-stealthy and questionably accurate gun pod. The USAF removed guns from some of its planes back in the 1960s, and didn’t enjoy the resulting experiences in Vietnam. It has kept guns on all of its fighters ever since, including the stealthy F-22 and F-35. Many allies wanted the superior single-barrel 27mm Mauser BK-27 cannon, but ammunition standardization benefits trumped pure performance. Instead, the F-35 got General Dynamics’ 4-barrel GAU-22/A 25mm cannon and just 180 x 25mm rounds, good for 3 short passes at best. That compares poorly to 510 x 20mm rounds on an F-16.

The 3rd difference is that the F-35A uses a dorsal refueling receptacle that is refueled using an aerial tanker boom, instead of the probe-and-drogue method favored by the US Navy and many American allies.

The F-35A was the first variant to fly, in 2009. Officially, it’s now expected to reach Initial Operational Capability as a 12-24 plane squadron by December 2016 (Threshold), with a stretch goal of August 2016 (Objective).

GAO reports re: the F-35′s delayed software development suggest that this is extremely unlikely, however, and even a difficult late catch-up still leaves the problem of scheduling proper testing for Block 2B, the 1st instance with any combat capability. Even Block 3F’s 2018 target date for the end of the system development phase is at risk, which means that jets designated as Operationally Capable would have a wide array of deficiencies that would put them at added risk in serious combat.

F-35B: hover test

(click to view full)

The F-35B is expected to be the most expensive Lightning II fighter variant. According to US Navy documents, even planes bought after 2017 are expected to have an average flyaway cost of $135 million each. It will serve the US Marines, Royal Navy, other navies with ski-ramp equipped LHDs or small carriers, and militaries looking for an “expeditionary airplane” that can take off in short distances and land vertically. To accomplish this, the F-35B has a large fan behind the cockpit, and nozzles that go out to the wing undersides. Unlike the F-35A, it will use a retractable mid-air refueling probe, which is standard for the US Navy and for many American allies.

Those capabilities gives the plane a unique niche, but a unique niche also means unique challenges, and the responses to those challenges have changed the aircraft. In 2005, the JSF program took a 1-year delay because the design was deemed overweight by about 3,000 pounds. The program decided to reduce weight rather than run the engine hotter, because the latter choice would have sharply reduced the durability of engine components and driven life cycle costs higher. Weight cutting became a focus of various engineering teams, with especial focus on the F-35B because the weight was most critical to that design. Those efforts pushed the F-35B’s design, and changed its airframe. The F-35B gives up some range, some bomb load (it cannot carry 2,000 pound weapons internally, and the shape of its bay may make some weapons a challenge to carry), some structural strength (7g maneuvers design maximum), and the 25mm internal gun.

F-35B features

(click to view full)

The F-35B completed its Critical Design Review in October 2006, and the 2nd production F-35 was a STOVL variant. Per the revised Sept 16/10 program plan, the USMC’s VMA-332 in Yuma, AZ must have 10 F-35Bs equipped with Block IIB software, with 6 aircraft capable of austere and/or ship-based operations, and all aircraft meeting the 7g and 50-degree angle of attack specifications, in order to declare Initial Operational Capability.

Flight testing began in 2009, and Initial Operational Capability (IOC) was expected by December 2012, but flight testing fell way behind thanks to a series of technical delays. By 2013, the first operational planes were fielded to the USMC at Yuma, AZ. After several slips, it’s expected to reach IOC as a 10-16 plane squadron by December 2015 (Threshold), with a stretch goal of July 2015 (Objective).

Recent discoveries of structural cracking, and GAO reports re: software development, suggest that even using the new jets for full-scale training by then could be a challenge. Limited-capability Block 2B software is the best they can hope for, and it’s already significantly behind. The F-35B’s “combat capability” at IOC may end up being flatly untrue, and its best realistic case might be as a mere paper tiger. Korean-War vintage F-9 Cougar jets would be “combat capable,” too, in the sense that they could take off, land, and fire weapons. That isn’t an adequate standard for entrusting them with the safety of an MEU in 2016.

USN F-35C

(click to view full)

The F-35C is instantly recognizable. It features 30% more wing area than other designs, with larger tails and control surfaces, plus wingtip ailerons. These changes provide the precise slow-speed handling required for carrier approaches, and extend range a bit. The F-35C’s internal structure is strengthened to withstand the punishment dished out by the catapult launches and controlled crashes of carrier launch and recovery, an arrester hook is added to the airframe, and the fighter gets a retractable refueling probe. According to US Navy documents, average flyaway costs for F-35Cs bought after 2017 will be $125.9 million each.

The US Navy gave up the internal gun, and the aircraft will be restricted to 7.5g maneuvers. That’s only slightly lower than the existing F/A-18E Super Hornet’s 7.6g, but significantly lower than the 9g limit for Dassault’s carrier-capable Rafale-M. Tests have also highlighted issues with slow transonic acceleration.

The F-35C is expected to be the US Navy’s high-end fighter, as well as its high-end strike aircraft. This means that any performance or survivability issues will have a disproportionate effect on the US Navy’s future ability to project power around the world.

The F-35C was the last variant designed. It passed its Critical Design Review in June 2007, and the first production version was scheduled to fly in January 2009. The F-35C’s rollout did not take place until July 2009, however, and first flight didn’t take place until June 2010. After several slips, the F-35C is now expected to reach IOC as a 10-plane squadron by February 2019 (Threshold), with a stretch goal of August 2018 (Objective).

These are much more realistic dates than the other variants, given GAO reports re: software development progress, but the F-35C is expecting to hit IOC with Block 3F software, whose 2018 target date is already very much at risk. In March 2014, the USN added another layer of uncertainty with plans to stall F-35C orders for 2 years if there are further budget cuts.

http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com...family-capabilities-and-controversies-021922/