Gyllis1

Respected Leader

Vittu mikä vatipää.Australialainen senaattori: "onko totta että pump-jet sukellusveneet voivat sukeltaa vain 20 minuutin ajan?"

Australialainen amiraali: ""

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Vittu mikä vatipää.Australialainen senaattori: "onko totta että pump-jet sukellusveneet voivat sukeltaa vain 20 minuutin ajan?"

Australialainen amiraali: ""

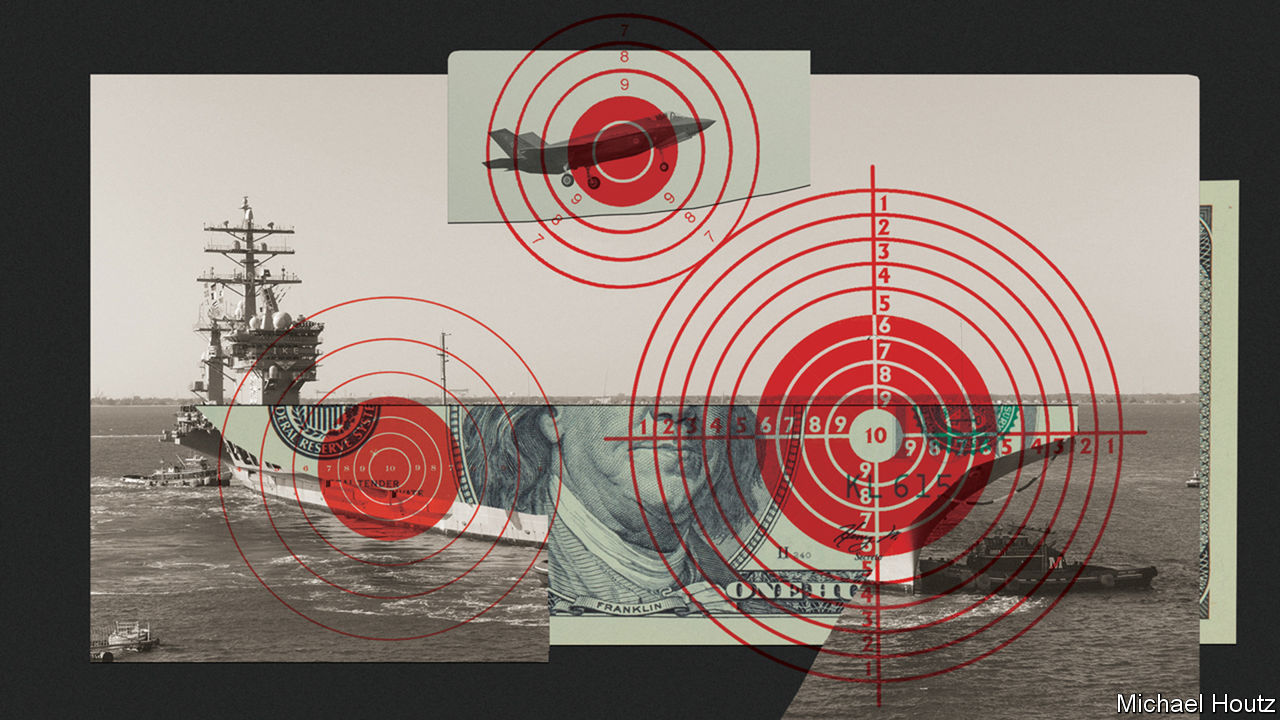

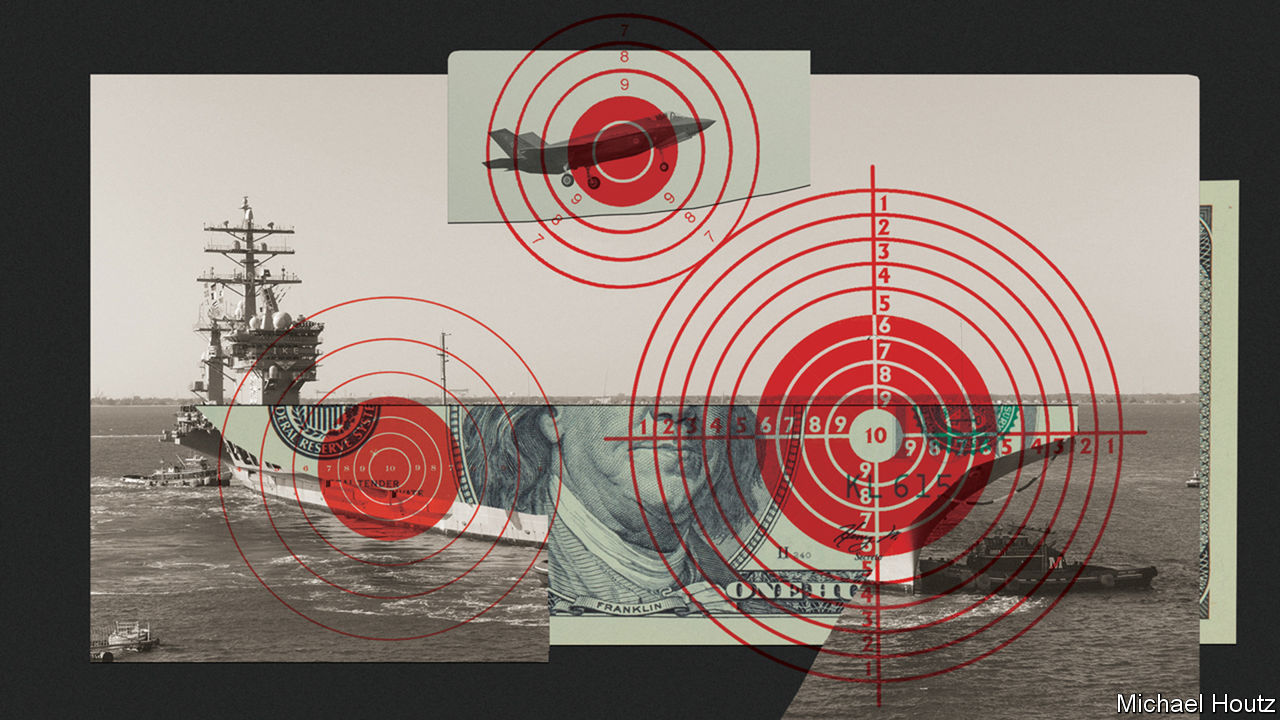

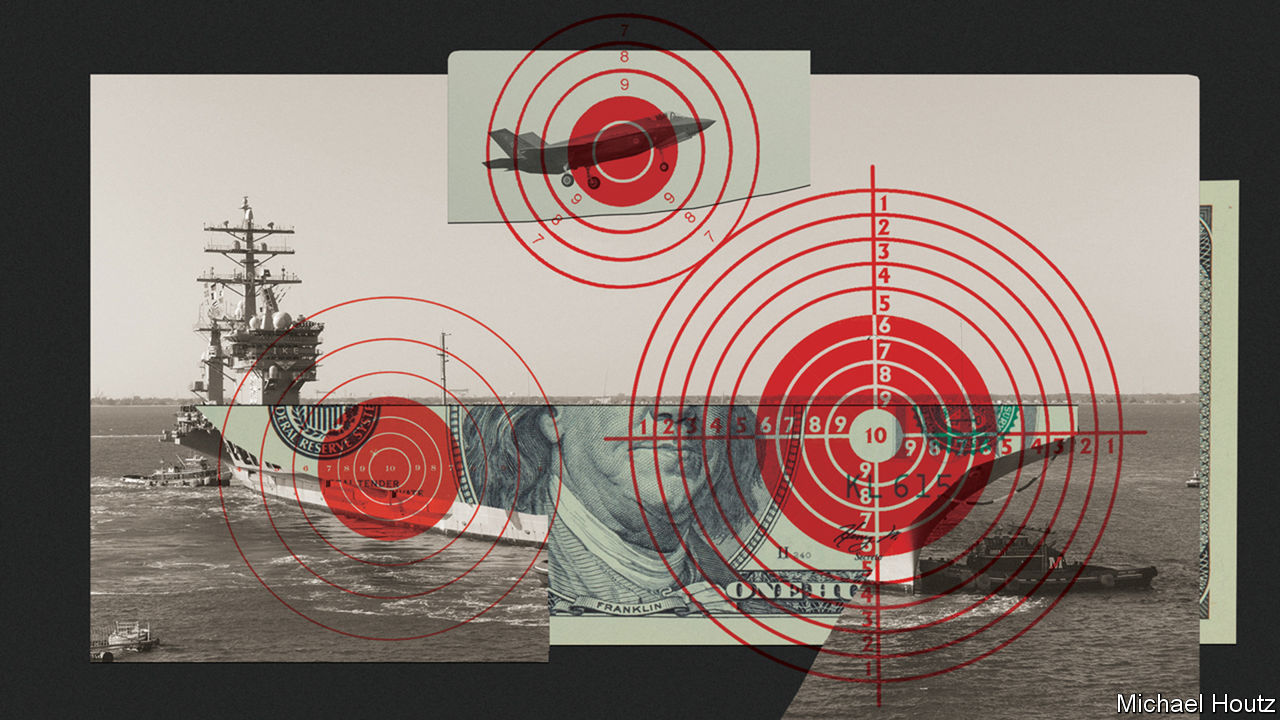

IN 2016 THE Admiral Kuznetsov, Russia’s sole aircraft-carrier, spluttered north through the English Channel belching thick black smoke. She was returning from an ignominious tour of duty in the Mediterranean. One of the 15 warplanes with which she had been pounding Syria had crashed into the sea; another had lurched off the deck after landing. When she finally docked near Murmansk a 70-tonne crane smashed into her deck.

The hapless Kuznetsov “is largely a white elephant with no real mission,” in the words of Michael Kofman, an expert on Russia’s armed forces. So why bother paying for the refit she has been undergoing ever since? “For the appearance”, says Mr Kofman, “of being a major naval power.”

Floating runways have signified naval seriousness for most of the past century. Originally seen as a way to provide air cover for other ships, the second world war saw aircraft-carriers and their air wings become the main way that fleets fought with each other. That role was largely lost after 1945, as the Soviet Union was not a naval power; the heart of the cold war lay on central Europe’s plains and in third-world hinterlands. But despite the lack of a high-seas competitor America made its carriers mightier still, using them to establish air superiority wherever it chose.

Carrier planes flew 41% of America’s combat sorties in the Korean war and more than half of its raids on North Vietnam. In the first three months of the Afghan war in 2001, carrier-based jets mounted three-quarters of all strike missions. Two years later, when Turkey and Saudi Arabia refused to allow their territory to be used for attacks on Iraq, America deployed the combined might of five aircraft-carriers to mount 8,000 sorties in the first month of its invasion. When Islamic State blitzed through Iraq in 2014 the USS George H.W. Bush rushed from the Arabian Sea to the Gulf. For more than a month the only air strikes against IS were launched from its four catapults.

The 11 supercarriers that America’s navy is required by law to have on its books make it a power like no other, able to fly fighters, bombers and reconnaissance aircraft wherever it likes without the need for nearby allies to provide airbases. The other countries with carriers capable of launching jet aircraft—Britain, China, France, India, Italy, Russia and Spain—make do with smaller and less potent vessels. But their numbers are increasing. Britain, India and China are all getting new carriers ready. Britain is settling for two; India aspires for three; China plans to have six or so by 2035. Japan is joining the club. In December 2018 it announced that it would convert its two Izumo-class destroyers to carry jets.

Is this fashion for flat-tops well advised? Carriers have long been threatened by submarines. During the Falklands war Argentina’s navy kept its only carrier skulking in port for fear of British submarines. Now they are increasingly threatened above the waterline, too, by ever more sophisticated land- and air-launched anti-ship missiles. To remain safe, carriers must stay ever-farther out to sea, their usefulness dropping with every nautical mile. Missile improvements also threaten the ability of the carriers’ air wings to do what is required of them, nibbling away at their very reason for being.

“The queen of the American fleet...is in danger of becoming like the battleships it was originally designed to support: big, expensive, vulnerable—and surprisingly irrelevant to the conflicts of the time,” writes Jerry Hendrix, a retired American navy captain. Are the countries devoting vast sums to their carrier fleets making a colossal mistake? And if so, what does that mean for the way America projects its power and protects its allies?

Americans like their aircraft-carriers large, like their cars and restaurant servings. They also insist on them being good. This makes them very expensive. When it was commissioned in 2017, the 100,000-tonne USS Gerald R. Ford, the first in a new class of carriers, became the priciest warship in history at $13bn. That is about what Iran spends on its entire armed forces each year, and almost twice what the George H.W. Bush, the last of the earlier Nimitz class of carriers, had cost a decade earlier.

The ego’s writing cheques

And that is before you sail or fly anything. In 1985, while he was making “Top Gun”, a jingoistic and intriguingly homoerotic paean to naval aviation, Tony Scott, a film director, was told that a single manoeuvre he wanted the USS Enterprise to make in order to get the perfect lighting would cost his studio $25,000. The annual cost of operating and maintaining a Nimitz-class carrier is $726m, not least because each has 6,000 people on board, almost twice as many as serve in the Danish navy. The planes cost a further $3bn-$5bn to procure and $1.8bn a year to operate.

Thriftier countries do have other options. The 65,000-tonne HMS Queen Elizabeth (“‘Big Liz’, as we affectionately call her,” according to Britain’s defence minister in June), currently exercising with its F-35 jets in the North Atlantic, cost Britain under £5bn ($6.2bn) to build. The next in its class, HMS Prince of Wales, not yet commissioned, is said to be coming in a fifth cheaper. There is also a second-hand market for those willing to accept a few scuffs on the paintwork. China’s debut carrier, the Liaoning, began life as the half-built hulk of the Kuznetsov’s sister ship. It was sold by Ukraine to a Hong Kong-based tycoon for a paltry $20m. He shelled out a further $100m to move it to China.

Yet even modestly sized carriers will inevitably soak up a good proportion of stretched military budgets. The capital cost of the Ford amounts to less than 2% of America’s annual defence budget; the Queen Elizabeth represents about 15% of Britain’s. General Sir David Richards, who served as Britain’s chief of defence staff from 2010 to 2013, urged the government to cancel the Prince of Wales because “We could have had five new frigates for the same money.” Sir David’s successor, General Nick Houghton, complained in May that Britain would “rue the day” it had splashed out on both. “We cannot afford these things. We will be able to afford them only with detriment to the balance of the surface fleet.”

It is one thing to be expensive. It is another to be expensive and fragile. In 2006 a Chinese Song-class diesel-electric submarine stalked the USS Kitty Hawk, a carrier, so silently while she was off Okinawa in the East China Sea that the first the Americans knew of it was when it surfaced just about 8,000 metres away. Getting that close would be harder in wartime, when the ships, subs and aircraft around a carrier would be more alert to undersea lurkers. But China is fielding ever more submarines. Modelling by the RAND Corporation has found that Chinese “attack opportunities”—the number of times Chinese subs could reach positions to attack an American carrier over a seven-day period—rose tenfold between 1996 and 2010.

Submarines do not have to get that close to do harm; they, like surface ships and aircraft, can also launch increasingly sophisticated anti-ship missiles from far afield. China’s H-6K bomber, for instance, has a range of 3,000km and its YJ-12 cruise missiles another 400km. This July, General David Berger, the head of America’s Marine Corps, published new guidelines which acknowledged that long-range precision weapons mean that “traditional large-signature naval platforms”—big ships that show up on radar—are increasingly at risk.

The most frightening illustration of this threat is a 200-metre platform—roughly the length of a carrier deck—that sits in the Gobi desert. It is thought to be a test target for China’s DF-21D ballistic missile, a weapon that the Pentagon says is specifically designed to kill carriers. The DF-21D is a pretty sophisticated and pricey bit of kit. But Mr Hendrix calculates that China could build over 1,200 DF-21Ds for the cost of just one American carrier. A longer-range version, the DF-26, entered service in April 2018.

According to a study by CSBA, a Washington think-tank, in future wars American carriers would have to remain over 1,000 nautical miles (1,850km) away from the coastlines of a “capable adversary” like China to stay reasonably safe. Any closer, and they could face up to 2,000 weapons in a single day.

Viittaako tuo vain kyseiseen alukseen vai koko alusluokkaan? Toivottavasti luokkaan.Teksti on kiinnostava. Esim. QE:n rahoituskulut edustaa kuulemma 15% brittien puolustusmenoista. Onko mahdollista? Silloinhan Prince of Wales kanssa menisi 30% kahteen.

Aircraft-carriers are big, expensive, vulnerable—and popular

The queens of the fleet are too big to failwww.economist.com

Tässä tekstissä oli kiinnostavampaa tuo supercarrierien selviytymis-ja operointikyky etelä-Kiinan merellä. Näitä samoja huolia on esitetty jo vuosia ja niihin ollaan vastaamassa. Tekstissä ei tosin käsitellä vasta-aseiden kilpajuoksua lainkaan eli USA:n satelliittitiedustelua, OTH-tutkan herkkyyttä/häirintää, hypersoonisia asejärjestelmiä, sukellusvenetorjuntajärjestelmiä sekä USN:n lisääntyvää Tomahawk-risteilyohjuslavettien määrää sukellusveneissä ja mahdollisesti maassa.Teksti on kiinnostava. Esim. QE:n rahoituskulut edustaa kuulemma 15% brittien puolustusmenoista. Onko mahdollista? Silloinhan Prince of Wales kanssa menisi 30% kahteen.

Aircraft-carriers are big, expensive, vulnerable—and popular

The queens of the fleet are too big to failwww.economist.com

Gabriel, tosin ei ole varsinainen standardi merikontti

Just About Every Nation Has Secret Missile Platforms Hidden in Shipping Containers

The growing threat of containerized weapon systems highlights a new era of covert warfare, where unassuming shipping containers could potentially harbor devastating missile systems, altering the balance of power with a single, concealed strike.sofrep.com

Mitäs meidän konteissa on, mustien, Sergein ja Nemon lisäksi?

Gabriel

Gabriel, tosin ei ole varsinainen standardi merikontti

No joo, mutta yleinen mielikuva merikontista on se iso Nemon kätkevä.Hetken aikaa mietin, että missä olet töissä, mutta sitten muistin, että tiedänhän minäkin tuon.

Optimisti: "Lasi on puoliksi täynnä."Sehän on pelkkä asennoitumiskysymys ovatko siilot puolitäynnä vai puolityhjät

Mjoo, zenaattori on pihalla kuin lumiukko propulsiosta ja kyselee gekados-alueen tietoa sukellusajoista, mutta admirable olisi voinut hieman helpottaa ja kertoa vaikka mihin ranskalaiset tai saksalaiset aippi-dieselit pystyvät, tietosuojaa rikkomatta. Ihan diplomaattisesti veti mutta näytti enemmän kuin hieman kybyltä tuon hair on firen tyhmiin kysymyksiin.Australialainen senaattori: "onko totta että pump-jet sukellusveneet voivat sukeltaa vain 20 minuutin ajan?"

Australialainen amiraali: ""

Mitäs meidän konteissa on, mustien, Sergein ja Nemon lisäksi?

Ai sinnekö se lähtikin.Gabriel

Optimisti: "Lasi on puoliksi täynnä."

Pessimisti: "Lasi on puoliksi tyhjä."

Teekkari: "Lasi on alunperin väärin mitoitettu."

Humanisti: "Siinähän on pelkkää vettä."

Militaristi: "Lasista viis, tarvitsemme lisää ohjuksia. Ai niin, ja panssarivaunuja."Optimisti: "Lasi on puoliksi täynnä."

Pessimisti: "Lasi on puoliksi tyhjä."

Teekkari: "Lasi on alunperin väärin mitoitettu."

Humanisti: "Siinähän on pelkkää vettä."

Optimisti: "Lasi on puoliksi täynnä."

Pessimisti: "Lasi on puoliksi tyhjä."

Teekkari: "Lasi on alunperin väärin mitoitettu."

Humanisti: "Siinähän on pelkkää vettä."

Poliisi: "Lasissa on kotipolttoista."

Militaristi: "Lasista viis, tarvitsemme lisää ohjuksia. Ai niin, ja panssarivaunuja."

Tämä kulttuuriantropologi tyhjensi jo pajatson, muut olen enemmän tai vähemmän kuullut jossain muodossa...Pispalainen: No ei oo kauaa.

Kulttuuriantropologi: Lasi edustaa etuoikeutetun patriarkaalisen eliitin pyrkimystä sortaa marginalisoituja ja rodullistettuja vähemmistöjä rakenteellisen väkivallan keinoin.

Vesi on venäjäksi voda. Eli taitaa olla kytkös.Sivuraiteella vielä kymysys, onko sanoilla "vesi" ja "vodka" jotain etymologista kytkyä? Aina ihmetellyt.

No tuo selittää jotain ihmeellisyyksiä mitä nähnyt.Vesi on venäjäksi voda. Eli taitaa olla kytkös.